Female Main Characters Who Think Like Female Main Characters

Exploring Merida's role as Pixar's first female lead and what lies beneath the surface

Excitement abounds with Pixar's latest announcement that next year's film, Brave, features the studio's first female lead character, Merida. Long seen as a boys-only studio, Pixar's bold move captures the hearts and minds of those left unrepresented with the lamp's past offerings.

But is it truly a watershed moment for the studio?

Ignoring temporarily the fact that late last year male director Mark Andrews replaced female director Brenda Chapman, Merida hides an even deeper and darker secret beneath her ginger locks.

The Experience of Solving Problems

Viewed through the context of structure, complete stories focus on the process of solving a problem. The Main Character gives the audience a way into that experience and affords them the opportunity firsthand to see how things work out. In short, the audience becomes this character. However, certain structural choices within a story can make it difficult for a portion of the audience to connect directly with the Main Character. These somewhat unintended consequences arise as a result of how the central character thinks.

Linearity is from Mars, Holism is from Venus

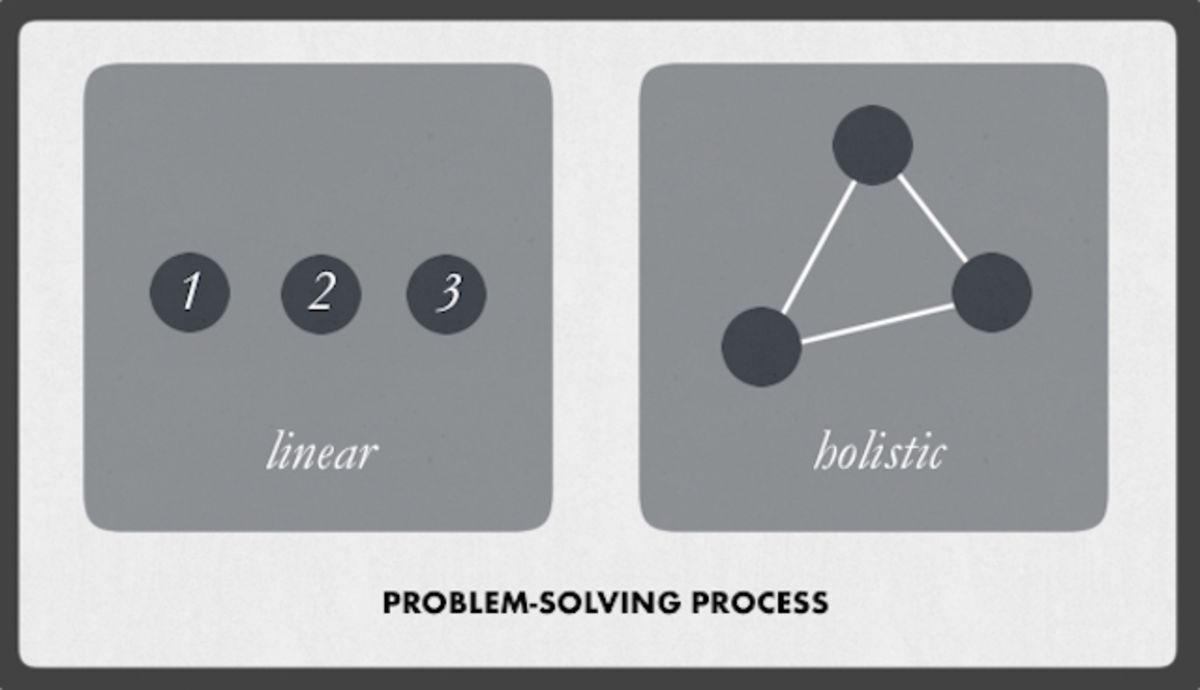

Main Characters come in two different flavors: those who approach problem-solving linearly and those who approach problem-solving holistically. They can do both, but one will always appear to be more prevalent than the other.

Male problem-solvers think primarily in terms of cause and effect. They see a problem and determine the sequential steps to solve it. In contrast, holistic problem-solvers think primarily in terms of balancing relationships. Rather than focusing on the individual steps, holistic solvers work the forces on disparate items, trying to shift the relationships between things.

Two completely different ways of approaching problems, each appropriate in its own way.

But what does this have to do with telling stories?

Male audience members expect their Main Characters to solve problems linearly. Why? Because at a base instinctual level, that is how they themselves solve problems. They don't understand how a character solves a problem any other way. Sure, they can intellectually understand how that process might work, but they'll never be able to truly relate to it. Shifting balances? If you're male and reading this, chances are you read that and thought, How can anyone solve problems that way? How does that even work? Isn't it easier to just attack the problem head on?

That same feeling reverberates through 1/2 of the audience out there when the Main Character doesn't solve problems linearly.

Merida won't take that chance.

The Mass Market Appeal of the Male Thinker

Female audience members relate easily to linear thinkers. They empathize with them just as much as they do with holistic thinkers, because at a base instinctual level they solve problems holistically. Holism understands linearity. They may wonder sometimes why the linear thinker can't see the forest for the trees, but they'll never have an issue relating ... because that's what they do. They relate.

So if linear Main Characters grab 100% of the audience and holistic Main Characters only grab half that, how do you think studio accountants and the executives they report to want their Main Characters to go about solving problems?

Beyond box office success, an even greater problem exists, particularly in the case of Brave, when it comes to the way a Main Character approaches problems. As difficult as it is for male audience members to empathize with holistic thinkers, it's ten times as hard for male writers or directors to infuse their Main Characters with this kind of thinking. The task becomes too monumental, even if an understanding of this concept exists. Much easier to go with what you know...especially if it means more tickets sold.

Merida will be a linear thinker. No doubt. She will do everything a boy can do and she'll do it with flair and strength. But she won't do everything a girl can do. She will appeal to both male and female audience members and Pixar's reign of the mass market will continue en masse. They will appear to be expanding their horizons, but in reality, they won't.

Merida won't truly be a female main character.

The Male Female

But that doesn't mean she won't be in good company: Ripley in Alien (and Aliens), Nina in Black Swan, Ree in Winter's Bone, Giselle in Enchanted, Maria in The Sound of Music...the list goes on and on. Male thinkers sheathed in female players. Again, in order to appeal to the largest audience, these stories focus on Main Characters who solve problems through cause and effect.

Think to Ree in Winter's Bone. If she is to care for her younger siblings, then she is going to have to find her father, regardless of the cost. A holistic thinker would have worked on shifting the balance with her uncle or with any of the other kindly citizens around her. Not to cause anything to happen per se, but rather to shift the balance of things so that a solution might present itself. But she didn't. Instead, she worked the problem step-by-step, following an Ozarkian connect-the-dots to her father's eventual location.

Maria, from The Sound of Music, took the same approach. She needs new clothes and the drapes need changing. Problem solved: she'll wear the drapes! And the kids can't possibly get their nice clothes soiled while playing, so they'll get some window dressing fashion as well. Cause and effect. Addressing the problem at its source. This is why, when the Captain takes his first extensive lead, Maria can so easily disobey his rules. A holistic thinker would have given thought to maintaining the balance in their relationship, perhaps not allowing the children to climb trees or carry on in a way that might upset the Captain. But not Maria. The kids needed more playtime, and she knew exactly how to solve that problem.

Incidentally, Winter's Bone based its narrative on a novel by Daniel Woodrell. The Sound of Music, though based on a memoir by Maria von Trapp, was fictionalized as a story by Howard Lindsay and Russell Crouse. Mark Heyman, Andres Heinz and John McLaughin wrote Black Swan. Enchanted by Bill Kelly.

Notice a pattern?

To repeat, Debra Granik and Anne Rosellini had no intrinsic difficulties adapting Woodrell's original novel of Winter's Bone because holistic thinkers simply don't struggle with linearity. It is when linear thinkers try to write holistic thinkers that a story can run into trouble.

Brave won't take that chance.

The Holistic Female

If Pixar wanted to be truly revolutionary they would try and write a Main Character that approached problems holistically: Deanie in Splendor in the Grass, Tita in Like Water for Chocolate, Blanche in A Streetcar Named Desire, Amélie in Amélie, and Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice. These stories all feature Main Characters who solve problems by working on the balance between things, rather than the things themselves.

Faced with catering the marriage of her one true love to another woman, the Main Character of Like Water for Chocolate, Tita, bakes her heartache into the food she prepares. Soon disaster strikes--the wedding guests lose their minds, wailing over their long lost loves. Not exactly a clear case of cause and effect. A linear thinker would have confronted Pedro's decision or perhaps even run off in much the same way that Maria did in The Sound of Music. But Tita didn't. Instead she finds a way to shift the balance of her pain, preparing meals so sensual as if to communicate the essence of her love for Pedro without any consideration to the effect she might cause. Her approach, while foreign to some, was perfectly holistic. An approach that turned out to be an appropriate way to solve her problem.

Deanie, in Splendor in the Grass, took the same approach. She can't for the life of her understand why Bud doesn't like her. So what does she do? She shows up with another date. How the heck does that even make any sense? many of the male audience members think to themselves. Yet, to a holistic thinker, it makes perfect "sense". By creating a dynamic between her and Bud and the other men, she thinks that somehow she'll be able to balance things out. Shift the dynamics in her favor. Her approach is one of trying to change the relationships around her and the relationships with her. There is purpose, yet it is the means to that end that might seem foreign to some (at least, to yours truly it does).

Jane Austen wrote Pride and Prejudice. Laura Esquivel wrote Like Water for Chocolate. But here, the pattern starts to break down. Guillaume Laurant and Jean-Pierre Jeunet wrote Amélie. William Inge A Splendor in the Grass. Tennessee Williams A Streetcar Named Desire.

OK, but we're talking about Tennessee Williams here. If there ever was an exception to a rule of authors and their Main Characters, he would be it. And William Inge was both a contemporary of Williams and an accomplished playwright himself before he even accepted the Oscar for Splendor in the Grass (And technically there is a sub-story that features Bud as the Main Character). These are master writers, craftsmen who could write a wide range of characters on both sides of the problem-solving aisle. They are the exception.

The ability of Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Guillaume Laurant to accurately capture the intricacies of a holistic thinker like Amélie owes its presence to the country within which they live. Culturally, France is not a linear society (compared to say, the United States). If anything, the French seem to have a propensity for balancing their relations with other countries and ignoring any call for cause and effect problem-solving. Jeunet and Laurant are simply the products of a holistic society.

This writing of holistic Main Characters by male writers happens, but only by truly accomplished writers and by writers who want to explore a character who solves problems holistically.

Writing What You Think, Not What You Know

The elation that comes with Pixar's "brave" move should find temperance in the knowledge that not much has changed. Yes, Merida's appearance front and center stuns us, but the way she thinks and solve problems won't. She can't if the studio hopes to appeal to the largest possible audience. And she won't, particularly in light of the aforementioned director shuffle.

Instead, Merida will be yet another in the long line of boys in girl's clothing. Not that there's anything wrong with that. There have been many amazing and enthralling stories that have followed the same path. It's just that the notion that somehow this film will feel different than the Pixar films before it, or that it somehow showcases a turning point in the studio's history might be a bit of a jump in logic.

There are female Main Characters who think linearly just as much as there are male Main Characters who think holistically. Look to The X-Files for proof of that. In story, gender has no correlation with how a character goes about solving problems. In story, it is all about how a character thinks, not how a character looks. Gender be damned.

Still, while Merida may be pretty, beauty is only skin deep. So too is the notion that Brave represents a step forward and a chance to finally hear from the other side.

Advanced Story Theory for This Article

Dramatica refers to this concept of character as the Main Character's Problem-Solving Process. This term was originally called the Main Character's Mental Sex, but as you can imagine it stirred up all sorts of controversial and confusing conversation that was unnecessary. With the switch of Male Mental Sex to Male Problem-Solving and Female Mental Sex to Holistic Problem-Solving, the barriers to a greater understanding of story became a little easier to climb.

The only problem is that the connection between linear thinking and the male mind and holistic thinking and the female mind still needs addressing when it comes to the concept of Audience Reach. The male blind-spot exists in the difference between linear thinking and holistic thinking. This is why many tune out of "chick-flicks" or stories where the Main Character refuses to work in cause and effect.

The blind-spot for the female mind exists in a completely different area. Here, the Story Continuum becomes the deciding factor. Female audience members can empathize with Spacetimes but only sympathize with Timespaces. Deadlines and ticking clocks reveal their weakness of empathy. This is why most sports with a majority female audience focus on points (options) rather than quarters or periods (time).

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.