A Few Good Men

5 Steps Towards Writing like Aaron Sorkin

Step 1: Choose the Courtroom Drama Genre for your narrative structure.

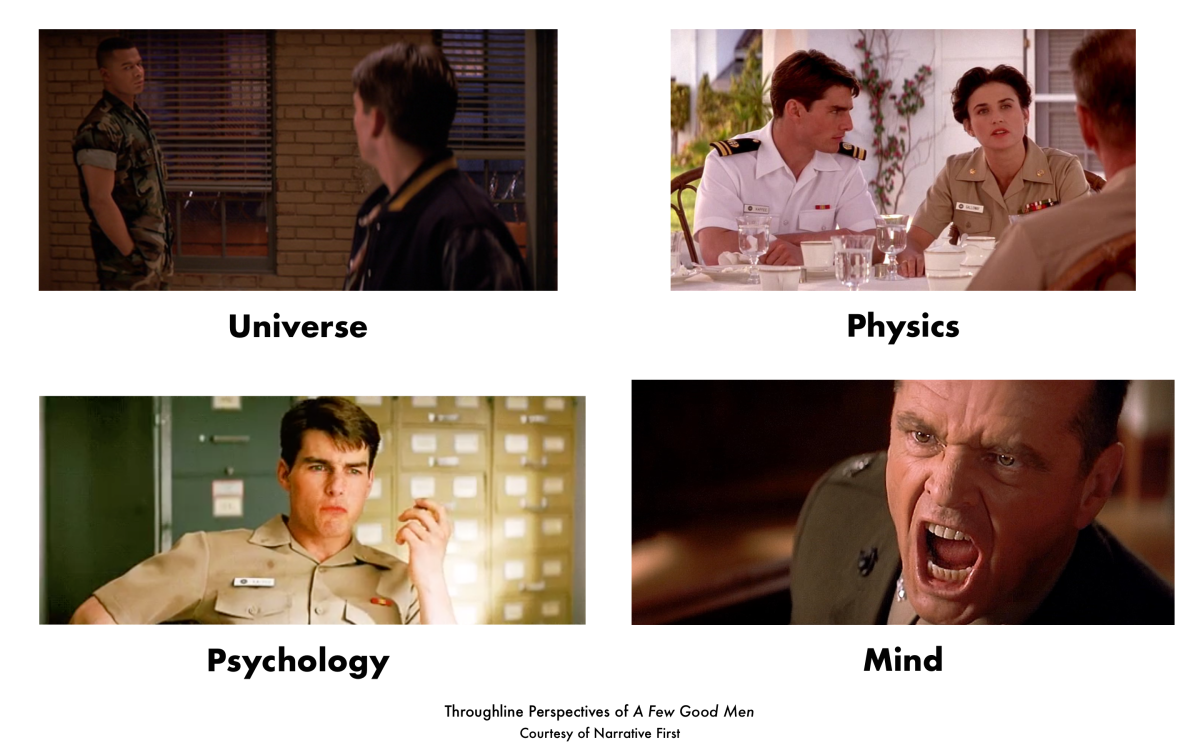

This sets the general area of conflict in the Objective Story Domain of Mind to Mind. And it places the area of personal conflict for the Main Character Domain in Psychology.

By default, it then forces the Obstacle Character Throughline into Physics and the Relationship Story Throughline into Universe.

Genre-ally speaking, almost all Courtroom Dramas share this common personality of narrative:

- The Objective Story Plot brings everyone into conflict over belief

- The Main Character Throughline explores a dysfunctional personality given to manipulation

- The Obstacle Character(s) challenge by means of problematic activities (like asking too many questions)

- and the Relationship Story Thorughline explores two people coming into conflict over the relative status (as in, you're supposed to salute an officer)

Step 2: Jump down to the very bottom of Dramatica’s narrative model and select either Reduction or Production as a Problem (this is Aaron Sorkin after all 😆). These two Elements encourage stories about characters who make a bigger deal about something, or cut back in order to save face.

We like the latter.

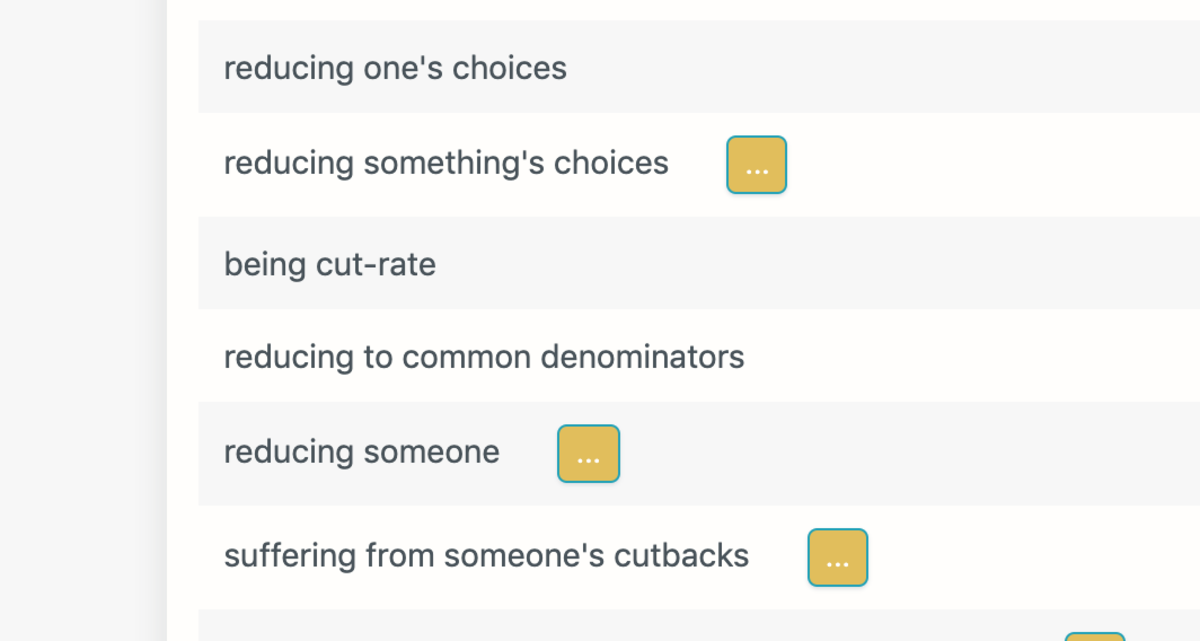

Scanning the list of Illustrations in Subtxt, we find:

- being cut-rate

as an example of Reduction as a Problem.

Perfect. That sounds exactly like the kind of character I want Daniel Kaffe to be (and it would be awesome if they could get 80s Tom Cruise to play the role 😎).

Reduction is the best Problem for this story. Kaffee is a cut-rate lawyer, and the Marine Corps operates from a cull-the-chaff perspective: while it may be tragic to lose a life here and there, in the end it probably saves lives.

Step 3: Follow the complete narrative structure presented to you by the Dramatica theory of story. Even better, upload it to Subtxt and start writing.

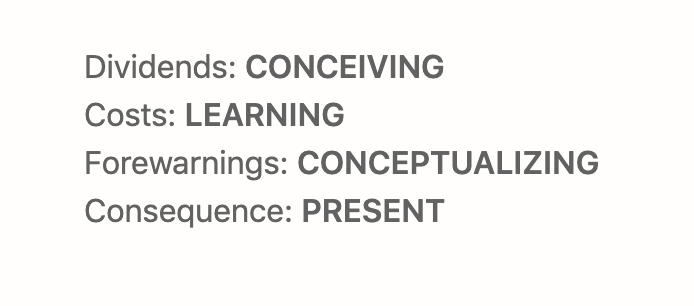

Note the Story Costs of Learning there in the storyform. That means at the end of the story—while everyone is celebrating in abject Triumph (a Success/Good ending)—-some of the characters will suffer negative Costs that have to do with Learning something.

Like Learning that you didn't do enough to save and protect your fellow soldier.

How the heck did Dramatica predict that ending just from our other choices? How did Sorkin know the Costs we’re Learning three years before the introduction of Dramatica?

Pure magic (the answer to both questions).

Step 4: Write dialogue like Aaron Sorkin.

Gotta admit—this one’s totally up to you. No amount of story theory or clever engineering is going to get you to “I object...I strenuously object! Oh, you strenuously object. Then I’ll take some time and reconsider.”

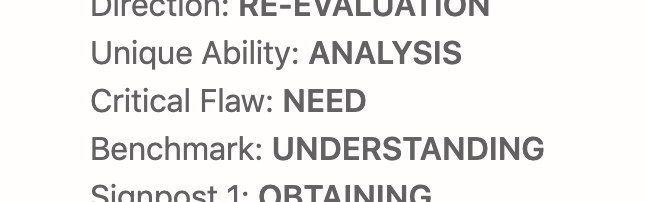

(Though, Dramatica will tell you that, based on your other choices, JoAnne’s Critical Flaw should be some kind of demand 😁)

Step 5: Profit.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.