Barbie

A tale of two Storyforms

Barbie made a bajillion dollars in 2023. Everyone seemed to love it, with many going back a second or third time, and some even going so far as to dress up for the occasion. Personally, I was interested enough to head out to the theaters for it (not a priority nowadays) as I was both a fan of Greta Gerwig’s (Little Women) and Noah Baumbach (While We’re Young). As wife and husband, I was sure they were going to nail the narrative and that I would leave the theater entertained and pleased with the final story.

I wasn’t.

Whether it was the cringe-worthy speech from Gloria about what women have to do in modern society, or the seemingly incongruent argument that everyone was happier with Ken in charge, I knew there was something off.

For the longest time, I couldn’t put my finger on the deficiencies and didn’t bother trying to find a way to put it into Subtxt. It was funny in parts, for sure, but something in the narrative just didn’t click for me. It wasn’t until the January 2024 edition of the Dramatica Users Group that I had an ‘aha’ moment that put everything into perspective.

The key to this story’s dissonance lies in the film’s unique narrative construction--a product of its two different writers.

The Dual Writer Dynamic

As mentioned, the wife-husband team of Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach shaped the story of Barbie. This collaboration led to a fascinating interplay of two different, yet incomplete, Storyforms that come together to shape the film's final narrative.

Storyform

A Storyform is essentially the DNA of a story. It's a unique combination of dramatic elements that outline the underlying structure of a narrative. Think of it as a blueprint that details the thematic arguments, character dynamics, plot progression, and overall message of a story. It's not the actual content or the words on the page, but rather the invisible forces that guide the direction and meaning of the narrative. When you understand a story's Storyform, you grasp the deep mechanics that make it tick, ensuring that every part of the tale contributes to a cohesive and resonant whole.

Mental Sex

Mental Sex is a concept in story theory that describes the operating system procedures of a story's mind. It's important to clarify that Mental Sex has nothing to do with the gender of the characters or the author, but rather with the nature of the story's approach to conflict resolution and inequity management.

Male Mental Sex is characterized by a step-by-step approach to solving problems. Stories with this kind of thinking tend to focus on cause and effect, moving from one logical point to the next in a direct line. A classic example of a Male Mental Sexed story where the Main Character is female can be seen in the film Aliens, where Ripley tackles challenges in a very systematic and logical way.

Female Mental Sex, on the other hand, is more about understanding and balancing relationships and interdependencies. It's less about linear causality and more about how everything in narrative relates to everything else. An example of a Female Mental Sexed story where the Main Character is Male is found in the movie The Social Network, where characters often navigate their dilemmas by considering the impact on themselves and others, looking for a balance and harmony in their resolutions.

Both approaches are equally valid and necessary, and great stories can be told using either method. The key is to be consistent with the type of Mental Sex chosen throughout the story to maintain a coherent conflict resolution process.

That doesn’t happen in Barbie.

Projecting Narrative Structure onto a Finished Work

There are two different Storyforms at work within Barbie. One takes on the aspects of Female Mental Sex and focuses on the subjective relationships between Barbie and human Gloria. The other assumes the trappings of a Male Mental Sex and focuses on the objective “plot” of Mattel losing Barbie and Ken’s taking over of Barbie-land.

The Objective Story Throughline in the Female Mental Sex Storyform lacks resonance with what we see in the film. The subjective Throughlines in the Male Mental Sex storyform (the relationship between Barbie and Ken) lack the subtle nuances found in the previous form.

Two Storyforms. Two authors.

Two almost-complete arguments.

It’s almost as if two people got together to write one story, yet didn’t quite completely see eye-to-eye on how the world works and functions in response to conflict.

And this is likely one of the sources of its monumental success.

Seamless Overlap of Storyforms

In spite of these contrasting points-of-view, the interplay between the two Storyforms crafted by Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach is not just a case of two narratives meshing together; it's about them enhancing each other. Let's explore some specific examples where these Storyforms overlap and why they work so seamlessly well together.

Identical MC and OC Plot Progressions

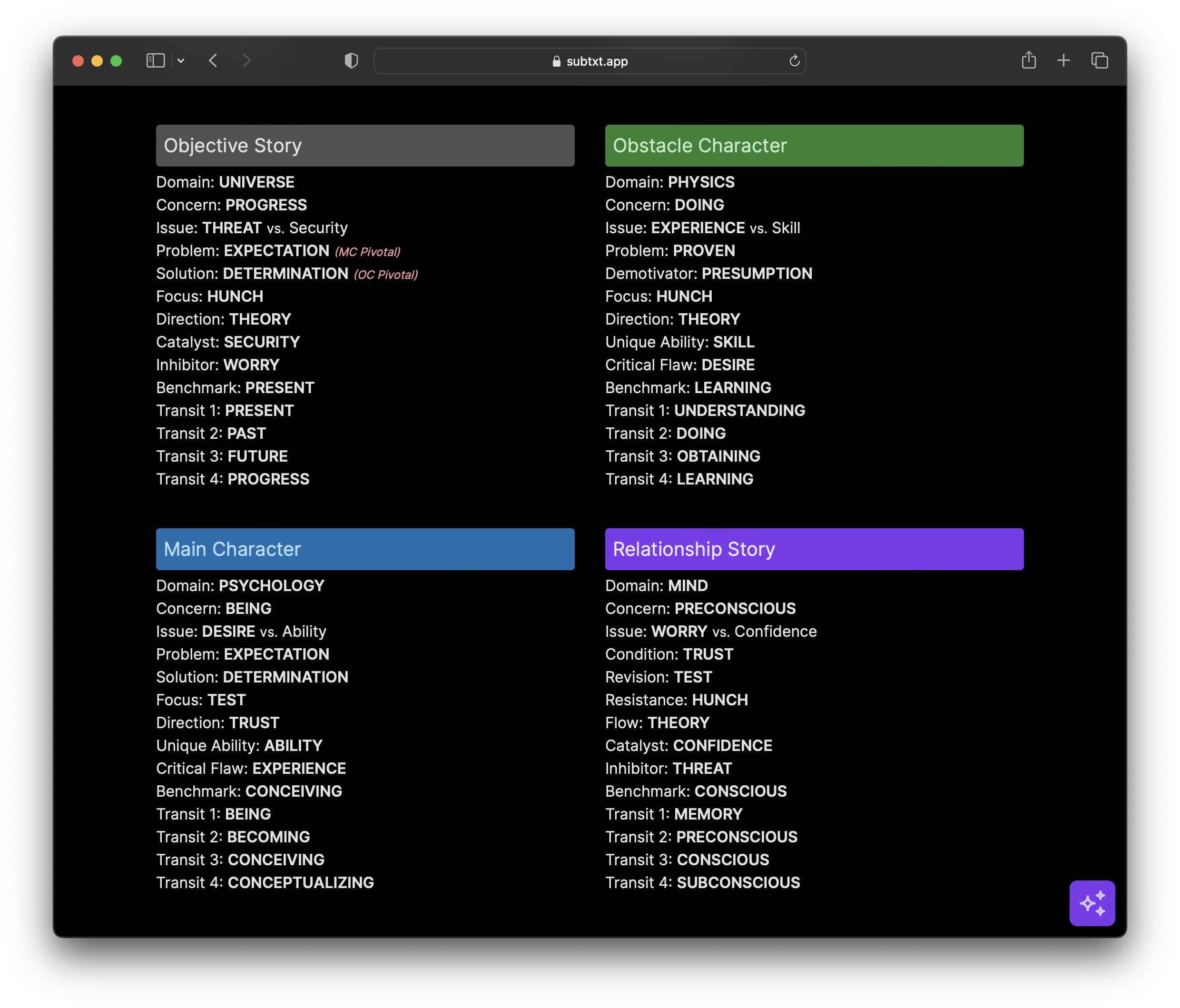

Firstly, both Storyforms share identical plot progressions (the order of thematic Transits from Act to Act) in the Main Character (MC) and Obstacle Character (OC) Throughlines.

Order of Transits in the Female Mental Sex Storyform:

This identical approach to thematic exploration means that regardless of whether we're looking at the film through Gerwig's subjective lens or Baumbach's objective perspective, the journey of Barbie (MC) and her interactions with the OC remain consistent. This consistency serves as a common ground, ensuring that the narrative doesn't stray too far into disjointed territory.

Order of Transits in the Male Mental Sex Storyform:

Emphasis on Different Aspects of the Storyform

The real beauty lies in how each Storyform emphasizes different aspects of the narrative. Gerwig's Female Mental Sex Storyform delves into the subjective Throughlines, focusing on the emotional and relational aspects of Barbie's world. Here, the story is rich in emotional depth and character-driven conflict. The OS Throughline, often downplayed with a Female Mental Sex Storyform, tracks the growth of Barbie from beginning to end (Past, Future, Progress, Present).

On the other hand, Baumbach's Male Mental Sex Storyform concentrates on the Objective Throughline (plot) to the exclusion of the other three. This perspective brings into focus the external challenges and societal implications within Barbie's universe, such as the threat to Mattel and the consequences of Barbie's actions. The OS Throughline Transits perfectly encapsulate this focus on her "escape" (Present, Past, Future, Progress).

By the end of the Female Mental Sex Storyform, Barbie's new "present" removes her from Barbie-land and sets her off in a new direction. By the end of the Male Mental Sex Storyform, Barbie's "determination" to choose for herself brings a solution of "progress" and development to Ken and the rest of those left behind.

The Harmony in Differences

What's remarkable is how these differences aren't monumental but rather complementary. The subjective and objective throughlines don't clash; instead, they create a harmonious balance, making the overall story more robust and multidimensional. This synergy is a testament to Gerwig and Baumbach's skill in weaving together their distinct narrative styles to form a cohesive and engaging film.

Greta Gerwig’s Approach: The Female Mental Sex Storyform

Greta Gerwig's contribution is likely the Female Mental Sex Storyform, and not just because she herself is female. Often, the trend supports the presumption that the gender of an author matches the Mental Sex of a narrative, but Gerwig’s previous work Little Women challenges that assumption.

In Little Women, Main Character Jo March is a Main Character who is Jo is very goal-oriented, direct, and tends to tackle problems head-on. Her determination to achieve her goals as a writer and to live life on her own terms, despite the societal expectations of her time, is indicative of cause-and-effect logic, a characteristic of the Male Mental Sexed Main Character.

The Barbie whose personal issues do not include Ken and/or the “escape” from Barbie-land is not like this at all. She exhibits a Female Mental Sexed approach as she tends to resolve problems by looking for balance and harmony, considering the emotional and relational aspects of the situation.

Barbie's approach is more holistic and integrative, often seeking to understand and empathize with others before taking action. In her relationship with Gloria, Barbie uses Female Mental Sex techniques to navigate conflicts and challenges by fostering understanding and cooperation, rather than seeking to dominate or impose a solution.

Noah Baumbach's Perspective: The Male Mental Sex Storyform

With our assumption that Gerwig supplied the Female Mental Sex side of things, that leaves Noah Baumbach to the Male Mental Sex Storyform.

In this Storyform, the Objective Story Issue resonates with the theme of Threat. This becomes particularly poignant as the board of Mattel grapples with the unexpected exit of Barbie, leaving a power vacuum that Ken eagerly fills.

The comedy in this Storyform springs from a familiar vein of conflict, primarily driven by “Expectation.” The characters within Barbie-land, both those who conform and those who rebel, find themselves entangled in the web of societal norms. The humor emerges as we witness the characters navigate the pressures and assumptions placed upon them, each in their own unique and often absurd ways as they fulfill others’ expectations.

While Ken's role as the Obstacle Character and his dynamic with Barbie are integral to the narrative, their presence is subtler in this Storyform. The Relationship Story Throughline, which usually vibrates with tension and resonance, here plays a softer tune. Ken and Barbie's interactions, though crucial, are turned down in the narrative mix, allowing the broader themes of expectations and societal pressures to take center stage.

Avoiding the Cringe

But what about that scene with Gloria?

In the world of storytelling, there's a particular kind of squirm-inducing moment that every audience dreads: the cringe-worthy scene. It's that moment when a character launches into a monologue that feels more like a lecture than a natural part of the narrative. This often happens when characters are not just embodying the Storyform, but speaking it out loud, as if they're reading from a script designed to hammer home the theme rather than living it.

This is the problem with that moment where Gloria gives a long-winded speech about the challenges women face in modern society.

Barbie's Male Mental Sex Storyform Details:

The Obstacle Character Concern in the Barbie Storyform (both of them) is “Doing”, which means the focus is on conflict arising from activities and endeavors. Instead of illustrating this through compelling action and interaction, Gloria's speech turns into a recitation of the Storyform. She's not just addressing the theme; she's broadcasting it without the subtlety of storytelling.

This is a classic case of telling rather than showing. Great stories weave their themes into the fabric of the narrative, allowing the audience to discover the message through the characters' experiences. When Ken, in another storyline with a Male Mental Sex Storyform, demonstrates the theme through his actions, the message is conveyed with far greater impact. His deeds speak louder than any speech could, engaging the audience and inviting them to draw their own conclusions.

Characters speaking the theme outright is problematic because it disrupts the immersive experience of a story. No one wants to be lectured to; they want to be told a story. The Storyform is a blueprint for creating narrative conflict and thematic coherence, not a script for characters to recite. When characters start speaking the Storyform, it's as if the writer is afraid the audience won't "get it" unless it's spelled out for them. But this underestimates the audience's intelligence and their desire to engage with the story on a deeper level.

To avoid these cringe-worthy moments, writers should trust their Storyform and use it as a guide to craft scenes that show, not tell. Let the characters live the theme through their choices and actions. Let the audience feel the theme through the drama and tension of the story. That's the essence of powerful storytelling.

Understanding Storyforms and Their Impact

The intriguing aspect of Barbie’s narrative lies in the merging of these two incomplete Storyforms--regardless of how much of it is read directly the audience. This combination brings a unique flavor to the film, blending emotional depth with external conflict, yet it also introduces a certain disjointedness due to its dual nature.

This deep dive into the dual narrative structure of Barbie highlights how understanding the Storyform can illuminate why a story resonates or falls flat. It's a testament to the complexity and richness of storytelling, where the narrative structure plays a crucial role in shaping the viewer's experience.

Barbie serves as a fascinating case study in storytelling. By dissecting its narrative structure, we gain insight into the mechanics of story forms and how they influence our perception and enjoyment of a film. It's a reminder of the power and intricacy of storytelling, and how knowing the Storyform can deeply enhance our understanding and appreciation of films.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.