Knives Out

Learning how to play the game

In an interview with ArcLight Cinemas, Knives Out writer/director Rian Johnson admits to structuring the film from the get-go. He prefers to write from an outline—the blueprint of the whole, keeping him from getting lost in the weeds. One wonders if this process includes a gander at the Dramatica theory of story because this:

<ShowQuad :semantic_id="41400" :parent="true" class="w-3/5 mb-6 mx-auto" throughline="mc" title="Main Character Issue of Falsehood" subheader="Marta Cabrera (Knives Out)"></ShowQuad>

Insinuates that someone driven to suppress the truth (Falsehood) for fear of speculation will end up using PROJECTION to resolve her issues. 🤣🤣🤣

Marta Cabrera (Ana de Armas) is a nice person. She is honest, sincere, and would do anything to help those she loves—as long as it doesn’t involve lying. Telling a lie results in a gut physical reaction resulting in projectile vomiting. This “flaw” comes out of left field--it's so cartoonish that one speculates as to the source of this idea. Have you ever heard of someone throwing-up because they couldn’t tell a lie? Or could it be that Johnson found himself inspired by the quad of Elements under Falsehood in the Dramatica Table of Story Elements?

Cue Benoit Blanc.

Understanding the Opposite of Speculation

Many writers abandon Dramatica altogether. They intuit some truth to it, try it out for a couple of weeks, then ditch the theory wholesale claiming it arcane. Part of this abandonment is fear of unraveling significant preconceptions of ability and more in-depth investigation into self. Another part is understanding terminology assumed incompatible with storytelling. Induction? Reduction? How do you even begin to write a story about Production?

The narrative Element of Projection is another one, made even more disorienting with its relationship to Speculation.

In the current Dramatica model, diagonal relationships infer the most significant conflict. Disbelief sits across from Faith, and Logic challenges Feeling. The highest most dynamic amount of friction for an Element of narratives lies diagonally across from it. Projection is the dynamic pair of Speculation, and therefore generates the most amount of conflict for that Element.

Most writers—particularly mystery writers—get speculation. To speculate is to guess what could be based on what you know. The game of Clue is pure Speculation for the whole family to enjoy.

While some writers may see Projection and instantly think projectile vomiting, the truth is that to project is assert what will probably happen based on what you know. Like Walt Thrombey challenging Marta to do the right thing because of his access to the “right” kind of lawyer. Or Ransom confessing at the end:

RANSOM

...what do you have on me? Nothing. What? attempted murder -

(to Blanc)

I get arson for the bombing, maybe a few other charges, with a good lawyer I'll be out before you know it.

This act of Projection resolves the mystery of whodunit—but it only comes as a result of Marta willfully lying, knowing that it most likely end in a big giant mess. This personal Projection of hers leads to Ransom’s Projection, which leads to Marta projecting all over him.

The Crucial Elements of a Story

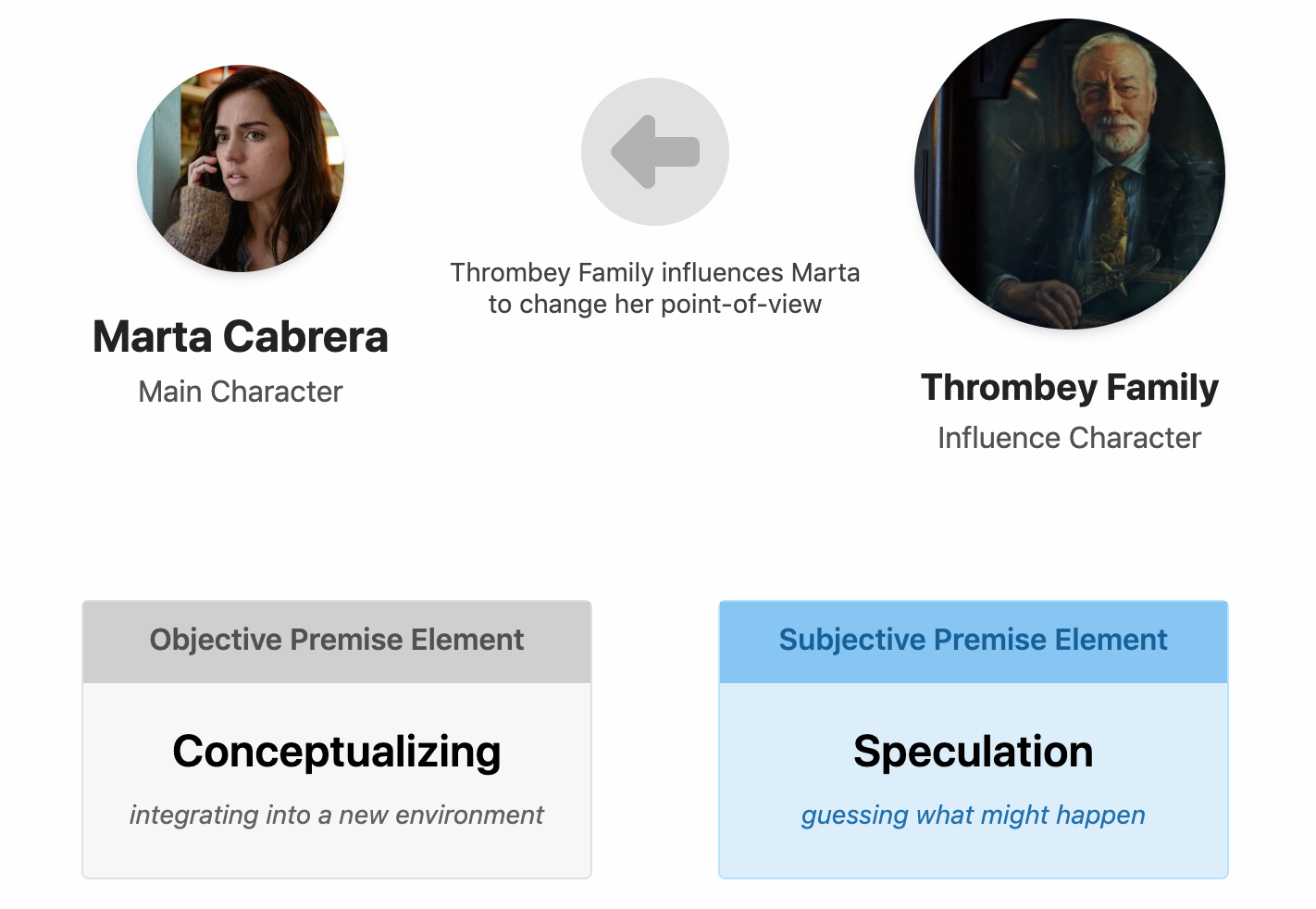

There is a difference between lying because of what you think might happen, and lying because of what you believe will probably happen. Both Speculation and Projection look to knowledge for answers; one finds possibility, the other probability. This dynamic fuels the engine of conflict in Knives Out.

In the beginning, Marta fears to lie because of what might happen to her—a personal justification of Speculation brought on by her mother’s speculative act of moving to America. Illegal immigrants live in constant fear of what might happen to them—with the possibility that they might be deported. Marta’s personal story is an analogy to this experience.

By the end, she gives up this method by lying, knowing what will probably happen. She doesn’t hide it, and she doesn’t suppress it, she comes out and says the lie without equivocation—and resolves the murder mystery story affecting everyone.

Speculation sits at the crossroads of conflict in Knives Out, illuminating the nexus point between the objective and subjective point-of-view. Speculation drives Marta’s personal journey, as much as it does the investigation into the death of the famed mystery novelist. Projection resolves both views, and cluing us in on the final message of the film:

::premise When you get out of your way and give up guessing what might happen, you can integrate into a new environment. ::

It works for those under the impression that they accidentally killed someone—and it works for those under the idea that they created an even greater crime sneaking into a country.

While on the surface, a classic whodunnit, underneath it all, the film speaks a message of subverting the power base in America. With Knives Out, writer Johnson proves that immigrants can beat the rich at their own game while maintaining a sense of dignity and grace foreign to those of privilege.

Effective story structure does more than merely make it easier for a screenwriter to finish a script—it makes it easier for those searching for where they fit in to appreciate how the game is played.

And how to win.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.