Finding The Plot Of Your Story Through Theme

Determining the progression of events is easy once you identify the family of Thematic issues present in your story.

Regarding the argument over the integration of Characters into Plot, the barometer of Theme rarely enters the conversation. Understood more as a simple statement of right and wrong, Theme observes from a distance–an outcast on the sideline of storytelling. The truth calls for Theme to step forward and play an integral part in the development of a narrative.

A Thematic Premise Leads to Nothing

Many primers on creative writing refer to Theme as the story’s premise. Lajos Egri’s The Art of Dramatic Writing popularized this idea with his definition of the composition of a “good premise”:

“Every good premise is composed of three parts, each of which is essential to a good play. Let us examine ”Frugality leads to waste. The first section of this premise suggests character–a frugal nature. The second part, leads to.” indicates conflict, and the third part waste, suggests the end of the play.

Greed leads to generosity. Ruthless ambition leads to destruction. Jealousy destroys itself and the object of its love. Anyone who has taken to pen to paper in the hopes of writing a great story recognizes this concept.

In his book, The Moral Premise: Harnessing Virtue and Vice for Box Office Success, Dr. Stan Williams describes a process of placing the premise on a continuum between vice and virtue. No longer content with “Ruthless ambition leads to self-destruction,” Dr. Williams adds “Ruthless ambition leads to self-destruction, but Benevolent justice leads to rightful honor.”

With this in mind, the young Author begins her story. Scene after scene, she depicts the fall of ruthless and ambitious characters; in-between she writes of benevolent and righteous characters ascending to great heights. And in the end, the Audience finds itself bored to tears with this black-and-white argument.

As a professional screenwriter and Scriptnotes podcast host Craig Mazin notes:

[A Moral Premise] is not a “theme” for the purposes of writing a movie. That’s a motif or subject matter. I mean, you can call it a theme, but it’s useless to the writer. It doesn’t help the writing.

Exactly.

The Bridge Between Character and Plot

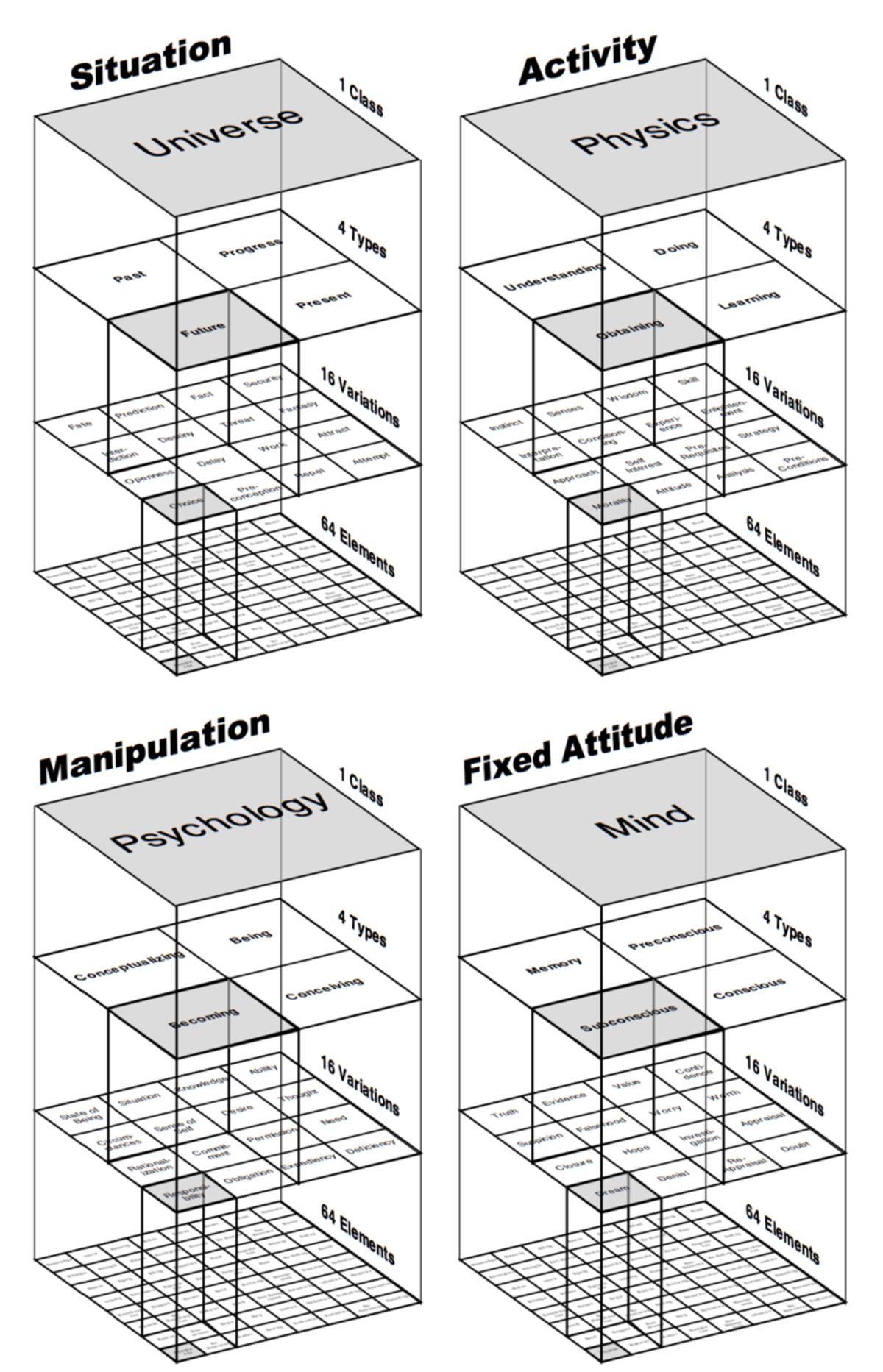

Look to the Dramatica Table of Story Elements hanging in your writing space or download a fresh copy from the official Dramatica site. Four towers cascade down the page, starting with Genre and working their way down to Character. Theme fills the gap between Plot and Character, tying the two narrative concerns of methodology and motivation with a barometer of evaluations.

Self Interest and Altruism provide a sliding scale for evaluating “Ruthless ambition.” Same with “greed,” “generosity,” and “jealousy.” In fact, a sampling of examples from Egri and Williams tends to reside in the same limited location of the narrative model; the same story told over and over again.

A brief scan of Dramatica’s thematic landscape reveals Commitments and Responsibilities, Senses and Interpretations, and Preconceptions and Openness. The totality of human evaluation lies waiting at this level for any Author to grab hold and make their own.

These evaluations also give clues towards the plotting of a narrative.

What You Find Above Exists Below

Consider the thematic Issues of Self Interest, Altruism, Approach, and Attitude. These four exist as a family of evaluations under the standard banner of Obtaining. A story that explores this area of theme–like The Matrix, Unforgiven, Reservoir Dogs, or Back to the Future sets a common Concern and Story Goal of Obtaining.

The thematic family of Instinct, Conditioning, Senses, and Interpretation requires plot development focused on Understanding something. The Usual Suspects, Inception, The Sixth Sense, and The Prestige toy with these four evaluations. Preconception, Openness, Delay, and Choice find a home in Concerns of the Future. Boyz n the Hood, Witness, Juno, and The Shawshank Redemption look to the Future as a common Goal of interest to the characters and plot themselves accordingly.

In all of these examples, the Type-level Concern that umbrellas the thematic evaluations below sets the plot for that particular narrative. Theme is more than a simple measuring stick between vice and virtue–Theme locks in the progression of Acts within a story.

Get Out

Understanding the connection between Theme and Plot helped me in my recent analysis of Get Out. At first, I felt the title of the film, and the dramatic concerns of the characters led to a shared interest of Conceiving: conceiving of a way out of both their heads and the dreaded Armitage family estate.

Looking at the family of thematic Issues resting below the Type-level Concern of Conceiving, I began to sense something incongruent. Permission, Deficiency, Need, and Expediency failed to describe the kind of conflict accurately, and thematic issues dealt with in the film.

Scanning the general area in and around these issues–as I knew, overall, that the kind of conflict explored dealt with Psychological manipulations and dysfunctional lines of thinking–I ran across State of Being, Sense of Self, Universe, and Circumstances.

Bingo.

These four thematic issues summed up the entirety of writer/director Jordan Peele’s narrative. Georgina, Walter, and Andre Hayworth’s Sense of Self. Mr. and Mrs. Armitage’s State of Being really awful people (actually, the entire family). Chris’s Universe of being the only black person in a sea of white people. And the overwhelming Circumstances of your physicality failing you. Put together, this unique family of disturbing Issues shapes the thematic conversation of Get Out.

And they also set the Plot of the film.

With Conceptualizing functioning as the shared mutual concern and Story Goal, the Failure to reach that Goal brings about a Story Consequence of Understanding.

Exploring these issues during the Obama era, Peele originally wrote a Failure ending for Chris. Instead of best friend Rod emerging from the red and blue lights, police offers converge on the bloodied and hapless Chris, with guns drawn. MisUnderstanding Chris as a cold-blooded murder they lock him up for life.

Regardless of Peele’s decision to break structure, the Plot Concerns of both Story Goal and Story Consequence remain the same. Choosing to focus on the problematic evaluations of State of Being, Sense of Self, Universe, and Circumstances locks in a Goal of Conceptualizing and a Consequence of Understanding.

Theme determines Plot.

Different Story, Same Story

While vastly different regarding characterization and genre, American Beauty shares the same connection between Theme and Plot as Get Out. As with the Armitage estate, the process of trying to integrate with one another creates problems for everyone.

Witnessing the shirtless guy next door lifting weights and this neighbor’s strange relationship with a teenage boy challenges Col. Fitts’ State of Being gay. Climbing the ladder of local real estate and envisioning a better life involves engaging in an illicit affair (Universe) for Carolyn. Figuring out where one fits into the high school caste system alienates Jane from cheerleader Angela through Sense of Self. And remaining catatonic to fit into suburbia with an obviously gay husband creates unacceptable Circumstances for Fitts’ wife, Barbara.

Like Get Out, this collection of thematic issues set a Story Goal of Conceptualizing–or integrating–and a Story Consequence of Understanding for American Beauty. In contrast to Peele, both writer Alan Ball and director Sam Mendes kept their original ending and allowed the plot to end in Failure: Lester realized the real beauty of his life moments before Fitts ended it because of the embarrassing misUnderstanding between them.

An actual failure to integrate into each other’s lives.

An Understanding of Theme That Helps

Instead of relying on outdated and presumption notions of “moral premise,” look to Dramatica’s robust and comprehensive understanding of Theme as the bridge between Character and Plot. Scour the topology of thematic Issues for words and concepts that speak to you as an Artist, and connect with that Intention deep within your heart. Once you hear their signal, acknowledge the family of Variations and look to the Type-level concern that wraps them together. There you will find a focal point for your Plot and a destination for the Characters in your narrative.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.