Perspectives and Players in a Functioning Story

Understanding the purpose of a character.

Many attach the Throughline, or thread of a story, to an individual character. They might call it the “B” storyline and say it is all about the Protagonist of the story. Or they might merely track the events of a single character from beginning to end.

A more comprehensive and accurate approach is to think of Throughlines as representing points-of-view, or perspectives of the conflict.

The Storymind Concept

The Dramatica theory of story rests on one central conceit: that a complete story functions as an analogy to a single human mind wrestling with an inequity. Character, plot, theme, and genre act as stand-ins for what goes on inside our heads when faced with conflict. An essential part of the majesty of this process is the ability to shift perspectives and to look at something and consider it from a different angle.

Our minds possess four distinct points-of-view:

- I

- You

- They

- We

We perceive and shape our world to these distinct points-of-view. The narratives we tell ourselves and those we project on others only mean something because of our ability to compare and contrast these alternative perspectives.

In a story, these four perspectives find correlation in the Four Throughlines:

- Main Character (I)

- Obstacle Character (You)

- Objective Story (They)

- Relationship Story (We)

These aren’t the perspectives of the individual characters—we’re not talking writing in first person or third-person omniscient. Instead, these are the perspectives assumed by that single human mind—the mind that is the story.

Seeing these Throughlines in context of perspectives affords Authors a more excellent range of mobility in writing their stories while maintaining thematic integrity.

And this is where thinking of the Relationship as a character—as mentioned in the previous article on Separating the Relationship from the Individuals in a Relationship—begins to pay off.

The Relationship Player

While it’s not ultimately clear in the Dramatica theory book and supporting materials, the Relationship Story Throughline perspective is not an argument—it’s one part of the story’s broader discussion, another point-of-view for the story’s mind to consider.

And just as you can hand off the Obstacle Character Throughline perspective from one ghost to another in A Christmas Carol or from Alfred to Robin to Barbara to the Joker in The LEGO Batman Movie, you can hand the We perspective of the Relationship Story Throughline off to other Relationship Players.

In Dramatica theory, a Player is an empty vessel—a container to hold a perspective. The length of time keeping that perspective can last an entire story, or it can last for a fraction of an Act.

In Aliens, James Cameron hands off the Obstacle Character Throughline from Newt to Lt. Gorman and Burke for one Act, and one Act only. The Familial Relationship between Ripley and Newt as mother/daughter lasts the entire story but doesn’t even fall into place until the closing minutes of the first Act. Before their initial engagement, another mother/daughter relationship steps in to fill the emotional void in the narrative—the relationship between Ripley and her birth daughter (later excised from the final film).

In the original screenplay of Aliens, the Relationship Story Throughline is handed off from one mother/daughter relationship to the next. It works because the links both share the same point-of-view and the same thematic material—namely the disruption of that bond through a twist of fate and its ultimate destiny to continue on through another.

This handing off of a perspective is not a one-time deal. The Audience deals with the totality of the story’s message, not the specifics of storytelling. A view can jump from one vessel to the next, and then back again—all without disrupting the integrity of the narrative.

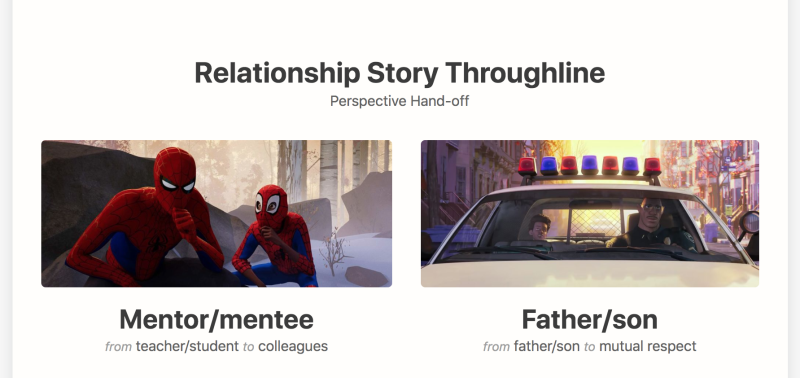

The dual relationships in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse take this approach. Father and son establish a Familial Relationship based on an imbalance of trust. Peter B. Parker arrives later, and the Mentorship he develops with Miles assumes that Problem of Trust. Later, father and son return to pick up that mantle of an inequitable relationship, only to pass it off back to the Mentorship (which then develops into something more closely resembling father and son).

The hand-off works because they both explore similar thematic content. As we will discover later, the other two prominent heartfelt relationships in Spider-Verse—the friendship between Miles and Gwen, and the Mentorship between Miles and his Uncle—sample alternative thematic material. They play an essential role, just not the part of delivering the Relationship Story perspective of We.

Assigning Buckets in Subtxt

A Player is a bucket for a perspective. In Subtxt, you can assign various Player “buckets” to different Throughlines. Their presence at the beginning of a Storybeat signals their ownership of that perspective for that particular Storybeat. This approach allows the writer to seamlessly hand-off perspective from one Player to the next—all without breaking the momentum and trajectory of their story.

Player Buckets split off into three major categories: Individuals, Groups, and Relationships. Individuals are self-explanatory. Groups are there to define a shared purpose of dramatic function commonly found in the Objective Story Throughline. A group of Stormtroopers helps provide the Antagonist role in the original Star Wars. A group of political cabinet members assists Protagonist Khrushchev in The Death of Stalin.

The Relationship option allows writers the opportunity to track different relationships with shared thematic material and mark the development of these relationships within the context of individual Storybeats.

If you were writing Aliens, you would create a Relationship Player bucket for the Familial Relationship between Ripley and her daughter, and another to hold the Maternal Relationship between Ripley and Newt. We make a distinction between the two because the bulk of thematic exploration in the latter rests heavily on the development of that maternal bond.

Furthermore, you would want to track the growth of that Maternal Relationship from beginning to end. Relationships are always changing, they’re never static—the moment stasis kicks in is the moment a relationship dies.

In Aliens, the Maternal Relationship grows from protector/ward to familial. As we will discover in later articles, a relationship not only grows but changes its very nature during that growth. Here we see the development of a link from a sense of the individuals to a blend where one loses track of the other, and a family is born.

Freedom and the Integrity of a Narrative

The greatest thing about this new understanding of the ability to hand-off the Relationship Story Throughline perspective is the freedom it affords writers. No longer chained to the idea that the Relationship must be between the Main Character and Obstacle Character for the entirety of a story and that their relationship must be an argument, Authors can now embrace their intuition while maintaining the integrity and consistency of thematic exploration that the Dramatica Theory provides.

Strangely enough—it’s always been there.

As Chris Huntley, co-creator of the theory explains, this concept of perspective-first was always an essential component of the theory:

When we wrote the book, both the Obstacle Character and Relationship Story throughlines were new concepts, though we did call it the Subjective Story before we changed it to MC vs. IC throughline – a label easier to understand but one that led to inaccurate interpretations. That’s why I/we changed it to Relationship Story in the third iteration.

An Objective view of the conflict between us (plot) juxtaposed against a Subjective view of the conflict between us (relationships). This is how a story works. It’s a model of how we think—not how we believe others think.

The more one sees the throughlines as perspectives, and one removes the ‘character’ from the throughline labels, the closer you get to a true understanding of them.

The Relationship Story Throughline is not about two characters arguing—it’s about a perspective of conflict available to us when approaching the inequities we find in our lives.

Relationship Players can maintain that perspective all by themselves, or they can hand it off to other couples for further exploration. In the end, the Audience compares and contrasts perspectives, not characters. The actual Players themselves fall by the wayside, allowing a greater appreciation of the meaning of the narrative.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.