The Relationship Story Throughline

The missing piece of narrative structure

Misunderstood for far too long, the Relationship Story Throughline balances the more objective concerns of plot with a complimentary subjective bond. Often felt as 'the heart of a story,' this relationship focuses on the dynamic conflict existing between individuals...and not always the two principal characters in a story.

Re-Imagining the Key Relationship of Any Story

Measuring the dynamics of growth by the space in-between characters.

In my twelve years of coaching and educating writers both professional and amateur, one common trait stands out: no one understands relationships. They know conflict and plot. They know character and theme. And they know how to put it all together to create something engaging and compelling for bringing to end. But they’re missing one piece.

Very few appreciate the conflict, plot, and theme that exists between characters.

Since its inception in 1994, the Dramatica theory of story taught that the critical relationship in a complete narrative, the “heart” of a story, was an emotional argument between the Main Character and Obstacle Character. This Relationship Story Throughline (once labeled the Main vs. Impact Story Throughline) pits the two principal characters against each other within an imagined philosophical battleground. Seen as a shortcut towards introducing groundbreaking concepts to the narrative discussion, this reductive take on the relationship dynamic led many writers astray—and even more to discount the theory altogether.

How could the romance between Indiana Jones and Marion be anything less than the emotional heart-center of Raiders of the Lost Ark? How could the friendship between Doc and Marty in Back to the Future be left out of similar discussions? With the Main vs. Impact litmus test, both of these critical relationships fail to meet what we all introvert know: emotional importance.

This series of articles on The Relationship Story changes all of that. By realigning our appreciation of narrative to original core concepts of Dramatica, and adding in practical experience building out meaningful stories with writers across all genres, we open up new frontiers of understanding story.

The Perspectives of Story

The Relationship Story Throughline is not the relationship between the Main Character and the Obstacle Character. The Relationship Story Throughline perspective is an emergent property of the consciousness of the Storymind—something not present within the unique aspects of I or You.

Emergence occurs when an entity is observed to have properties its parts do not have on their own.

The Relationship Story Throughline perspective is We.

And We are neither You nor I.

For many, this concept of splitting hairs around notions of subjectivity may appear overly complicated and semantic. For others, it may seem an impossibility to hold a We perspective that does not include self. I’m here to tell you that this complexity is both necessary and possible—particularly if you want to access the real emotional heart of your story.

It might even help you in your own relationships.

The Usual Suspects of Subjectivity

The original Dramatica theory book wasn’t wrong. More often than not this property does turn out to be the dynamic between the Main and Obstacle Character Players. The mentorship between Ben and Luke in Star Wars. The romance between Rick and Ilsa in Casablanca. The contentious friendship between Rus and Marty in True Detective: Season One.

While these couples indeed find time to argue, their relationship is not an argument. In fact, their relationship is 1/4 of the story’s argument—1/4 of the premise. Their disagreements and the basis for their point-of-view finds a home in other quarters.

The Four Throughlines of a complete narrative describe the perspectives of the single argument of the story. Characters and the relationships between them exist to hold and convey these points of view to the Audience. This arrangement allows Authors the opportunity to hand-off a perspective from one character to the next.

The classic example lies with the Ghosts in Dicken’s A Christmas Carol. One by one, and starting with Marley, the Ghosts relay their common perspective of influence on Scrooge. Looking back over the narrative retrospect, these four Ghosts act as one collective Obstacle Character.

The same possibility exists within the Relationship Story Throughline perspective.

Handing Off the Heart of a Story

The emotional core of Good Will Hunting dwells in the Therapeutic relationship between Will and Sean. The two share an intimate bond and grow from patient/therapist to close friends. Yet, another relationship exists within the film that shares a similar and meaningful friendship.

The Friendship between Will and Chuckie (Ben Affleck) carries the same thematic elements found in the Therapeutic Relationship. The do-or-die brotherhood that finds them fighting on the basketball court to protect each other also puts them at odds over each other’s personal survival. And their shared acknowledgment that their relationship had purpose resolves their differences—with heartfelt emotion.

The Friendship felt between both couples exists outside of any central plot development. Tangential to the objective concerns of a math genius hiding out as a janitor, these relationships reflect the importance of growth and understanding in the development of friendships.

And that’s why it’s essential to stop thinking of the Relationship Story Throughline in terms of an emotional argument.

The real purpose of the Relationship Story Throughline is to shine a light on the importance of growth between us in the real world—a chance to viscerally feel and understand this dynamic as we work to resolve the inequities in our lives.

Stories offer us an opportunity to appreciate our own conflicts. While we operate in a palpable sense in the real world, and while we have our own subjective personal issues, the subjective dynamics of growth that exist beyond us as individuals is equally as crucial to understanding our experience. Some might even say more important.

The more connected we become, the more essential it becomes for us to appreciate the dynamics at play between us. This newfound understanding of the Relationship Story Throughline of a narrative draws one step closer to understanding the purpose—and intent—of our relationships with one another.

Separating the Relationship from the Individuals in a Relationship

You and I are not We.

Ask anyone to describe their closest relationship when it’s going well, and they’ll answer with “We’re doing so well together” and “We’re really happy.” Ask them that same question when things are rough, and they’ll reply with “He won’t talk to me” or “I feel like I want something more.” When there is flow, we naturally gravitate towards the relationship; when there are resistances and conflict, we see the individuals.

Is it any wonder, then, that Authors struggle to illustrate the Relationship Story Throughline of their story accurately?

Authors naturally gravitate towards conflict and therefore, write about the individuals. They participate in He said/She said storytelling, penning the grief and struggle each feels as they come together, completely missing the flow of dynamic conflict that exists in the space between them.

Write about the relationship as if it was a character, and you avoid the trappings of the individual and capture the essence of this dynamic flow.

simply saying “the partners want different things in life and so can’t progress” risks becoming so vague it’s not actionable from a writing standpoint (because it doesn’t speak directly enough to the intersection of those differences), which is why it’s hard not to write, “John wants a baby, Sally wants to be free to travel the world, and the incompatibility of those desires starts to split their marriage apart”

Conflicting lines of thought do not describe a relationship. They portray the nature of those opposing views, but they don’t speak of the emergent property arising when two meet.

I know it might sound like splitting hairs, trying to differentiate between the loneliness the relationship feels with the isolation the individuals feel, but there is a qualitative difference.

The best approach to capturing this essence is to write a relationship as if it possesses a consciousness. Speak of the relationship’s feelings and concerns, drive, and purpose. Treat the relationship as if it were a part of life, and you’ll begin to crossover in your understanding of narrative.

The Space Between Things

Think of those with marital difficulties. Can one of those marriages be happy if one or both of the individual within are unsatisfied?

Absolutely.

There are many instances where one or both parties feels isolated and alone, yet the driving force between them is healthy, fortified, and happy. It may not be ideal for some—but to many, it’s more important than the individual concerns, which is why it is essential to be able to encapsulate it in a story.

That force between them--that marriage--takes on a life of its own. It is “happy.” And that’s what we would write about if we were Authors.

[a] relationship doesn’t have feelings. I can totally see why two people might feel isolated on their own and yet feel their marriage is strong, but that’s different from “the marriage” being happy.

Narrative functions as an analogy to our mind’s problem-solving process. Each area of the mind expresses its own form of consciousness. Stories replicate this reality through the various Throughlines, giving the Audience the experience of living within that mind.

Witnessing the space between things is an integral part of that experience.

A story is a person. A single mind.

Appreciating this connection between the mind and narratives helps us better understand the function of a Relationship Story Throughline in a narrative.

It also helps us appreciate the reality of our experience.

The Struggle for the Rational Mind

If a story is a model of the mind at work, then the individual Throughlines of that story represent the various perspectives available to that mind.

The Objective Story, or plot, offers a They perspective of the conflict.

The Main Character Throughline presents the first-person personal I point-of-view.

The Obstacle Character challenges that perspective by delivering the alternate You position.

Finally, the Relationship Story Throughline furnishes the We perspective.

As we began to see in the previous article, the Relationship Story Throughline does not have to be carried out by the Main Character and Obstacle Character. It certainly makes things more comfortable, but it is not a requirement.

Predominantly Male thinkers struggle—if outright can’t see—that We does not include I or You. They completely understand the separation between I and They (walk a mile in a man’s shoes) but they labor to do the same within a place of subjectivity (drift a mile in our boat). If We included I, then there would be no need for We.

You and I are a part of We just as much as You and I are a part of They—which is to say, they’re not. The Main Character Player holds the unique and subjective I perspective. This Player also holds an objective view—typically as Protagonist—by performing a function in the Objective Story Throughline. While the Author may draw connections between the subjective and the objective, one can’t be wholly objective when subjectivity exists.

Except in a story.

The Objective Story Throughline provides the objective point-of-view. The Relationship Story Throughline offers the subjective point-of-view of that Overall objective perspective.

It’s easier for Male thinkers to see the difference between I and They because they think in terms of separation and binary. They struggle to make the same distinction between I and We because they don’t consider in terms of holism and of the connectedness of things.

That’s why you can absolutely have a happy marriage where one of the parties is not pleased. It’s not about the individuals—it’s about that space between them—and that space has nothing to do with whether or not you or I am happy.

The Consciousness of a Narrative

Or is a different way to look at it that we imagine the marriage as a third person and we put ourselves deep inside this strange etheric bubble and say, “if I were a consciousness that suddenly existed inside this marriage, how would I describe it”? In that sense, the RS isn’t so much a perspective on its own but a sort of judgment the author is making about the relationship.

Absolutely, 100% this.

It’s the exact same concept as a sunrise being an Spacetime or a Timespace. A narrative (storyform) is the author’s judgment on everything—objectivity, perspective, and yes—relationships.

That “consciousness existing inside the marriage” is you—the Author.

this struck me in an odd way because in a literal sense there’s no such thing as a relationship as distinct from the two individuals. Relationships can’t “feel” anything (I’m talking outside of Dramatica here.) Only the people involved can feel something. In fact, even when you and I use the exact same word to describe our relationship, we’re not actually feeling the same thing, nor is the space between us feeling anything because it’s literally not there. In this sense, a relationship isn’t an entity but rather an effect: it’s what happens when you and I interact.

I bet if you asked Yoda you might get a different answer. 😁

When people speak of “laws of attraction” or “The Secret,” they’re trying to put words to this sense that there is something between us that doesn’t include You and I. They’re driven to tell this story because they’re trying to give meaning to our relationships that exist outside of the objective Objective Story Throughline. They’re not being deluded or suckered into a scam, they’re buying into it because it reflects how they see the world.

These lines of thought sound like a religion or a cult because they’re doing the same thing religion does for us on the other side in the Objective Story Throughline of our lives—they’re giving us a context for understanding what it all means.

It’s just doing it from a We perspective, which is why it sounds so weird and kooky to the more rationally-minded.

A story, or a narrative, is an attempt to ascribe meaning to our lives. We can’t simultaneously be both within and without ourselves in the same context (I and They), but we can in a story. Personal relationships are an integral part of that understanding. Those who see the individual components of a relationship prefer the objective view of things. Those who see the dynamics between individuals prefer the subjective.

Many fail to see the difference between I and We or You and Us—all you have to do is look to the countless number of relationships that dissolved because someone took the relationship for granted. They literally didn’t see We as being separate and worthy of consideration.

So yes, as far as the Author is concerned, in trying to find and give meaning to our experience, a relationship has a “consciousness.”

And it’s worthy of writing about.

Perspectives and Players in a Functioning Story

Understanding the purpose of a character.

Many attach the Throughline, or thread of a story, to an individual character. They might call it the “B” storyline and say it is all about the Protagonist of the story. Or they might merely track the events of a single character from beginning to end.

A more comprehensive and accurate approach is to think of Throughlines as representing points-of-view, or perspectives of the conflict.

The Storymind Concept

The Dramatica theory of story rests on one central conceit: that a complete story functions as an analogy to a single human mind wrestling with an inequity. Character, plot, theme, and genre act as stand-ins for what goes on inside our heads when faced with conflict. An essential part of the majesty of this process is the ability to shift perspectives and to look at something and consider it from a different angle.

Our minds possess four distinct points-of-view:

- I

- You

- They

- We

We perceive and shape our world to these distinct points-of-view. The narratives we tell ourselves and those we project on others only mean something because of our ability to compare and contrast these alternative perspectives.

In a story, these four perspectives find correlation in the Four Throughlines:

- Main Character (I)

- Obstacle Character (You)

- Objective Story (They)

- Relationship Story (We)

These aren’t the perspectives of the individual characters—we’re not talking writing in first person or third-person omniscient. Instead, these are the perspectives assumed by that single human mind—the mind that is the story.

Seeing these Throughlines in context of perspectives affords Authors a more excellent range of mobility in writing their stories while maintaining thematic integrity.

And this is where thinking of the Relationship as a character—as mentioned in the previous article on Separating the Relationship from the Individuals in a Relationship—begins to pay off.

The Relationship Player

While it’s not ultimately clear in the Dramatica theory book and supporting materials, the Relationship Story Throughline perspective is not an argument—it’s one part of the story’s broader discussion, another point-of-view for the story’s mind to consider.

And just as you can hand off the Obstacle Character Throughline perspective from one ghost to another in A Christmas Carol or from Alfred to Robin to Barbara to the Joker in The LEGO Batman Movie, you can hand the We perspective of the Relationship Story Throughline off to other Relationship Players.

In Dramatica theory, a Player is an empty vessel—a container to hold a perspective. The length of time keeping that perspective can last an entire story, or it can last for a fraction of an Act.

In Aliens, James Cameron hands off the Obstacle Character Throughline from Newt to Lt. Gorman and Burke for one Act, and one Act only. The Familial Relationship between Ripley and Newt as mother/daughter lasts the entire story but doesn’t even fall into place until the closing minutes of the first Act. Before their initial engagement, another mother/daughter relationship steps in to fill the emotional void in the narrative—the relationship between Ripley and her birth daughter (later excised from the final film).

In the original screenplay of Aliens, the Relationship Story Throughline is handed off from one mother/daughter relationship to the next. It works because the links both share the same point-of-view and the same thematic material—namely the disruption of that bond through a twist of fate and its ultimate destiny to continue on through another.

This handing off of a perspective is not a one-time deal. The Audience deals with the totality of the story’s message, not the specifics of storytelling. A view can jump from one vessel to the next, and then back again—all without disrupting the integrity of the narrative.

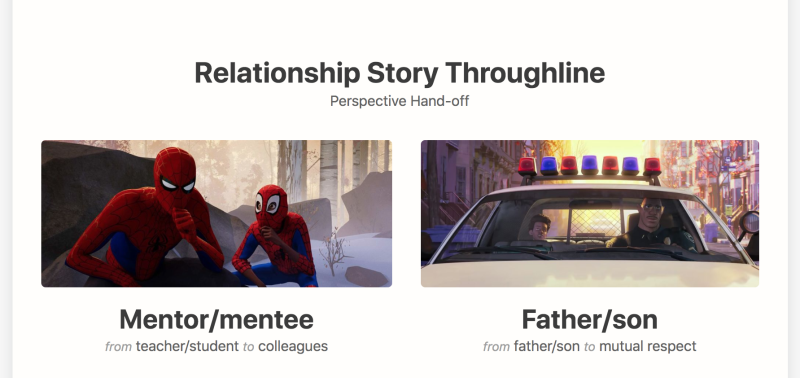

The dual relationships in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse take this approach. Father and son establish a Familial Relationship based on an imbalance of trust. Peter B. Parker arrives later, and the Mentorship he develops with Miles assumes that Problem of Trust. Later, father and son return to pick up that mantle of an inequitable relationship, only to pass it off back to the Mentorship (which then develops into something more closely resembling father and son).

The hand-off works because they both explore similar thematic content. As we will discover later, the other two prominent heartfelt relationships in Spider-Verse—the friendship between Miles and Gwen, and the Mentorship between Miles and his Uncle—sample alternative thematic material. They play an essential role, just not the part of delivering the Relationship Story perspective of We.

Assigning Buckets in Subtxt

A Player is a bucket for a perspective. In Subtxt, you can assign various Player “buckets” to different Throughlines. Their presence at the beginning of a Storybeat signals their ownership of that perspective for that particular Storybeat. This approach allows the writer to seamlessly hand-off perspective from one Player to the next—all without breaking the momentum and trajectory of their story.

Player Buckets split off into three major categories: Individuals, Groups, and Relationships. Individuals are self-explanatory. Groups are there to define a shared purpose of dramatic function commonly found in the Objective Story Throughline. A group of Stormtroopers helps provide the Antagonist role in the original Star Wars. A group of political cabinet members assists Protagonist Khrushchev in The Death of Stalin.

The Relationship option allows writers the opportunity to track different relationships with shared thematic material and mark the development of these relationships within the context of individual Storybeats.

If you were writing Aliens, you would create a Relationship Player bucket for the Familial Relationship between Ripley and her daughter, and another to hold the Maternal Relationship between Ripley and Newt. We make a distinction between the two because the bulk of thematic exploration in the latter rests heavily on the development of that maternal bond.

Furthermore, you would want to track the growth of that Maternal Relationship from beginning to end. Relationships are always changing, they’re never static—the moment stasis kicks in is the moment a relationship dies.

In Aliens, the Maternal Relationship grows from protector/ward to familial. As we will discover in later articles, a relationship not only grows but changes its very nature during that growth. Here we see the development of a link from a sense of the individuals to a blend where one loses track of the other, and a family is born.

Freedom and the Integrity of a Narrative

The greatest thing about this new understanding of the ability to hand-off the Relationship Story Throughline perspective is the freedom it affords writers. No longer chained to the idea that the Relationship must be between the Main Character and Obstacle Character for the entirety of a story and that their relationship must be an argument, Authors can now embrace their intuition while maintaining the integrity and consistency of thematic exploration that the Dramatica Theory provides.

Strangely enough—it’s always been there.

As Chris Huntley, co-creator of the theory explains, this concept of perspective-first was always an essential component of the theory:

When we wrote the book, both the Obstacle Character and Relationship Story throughlines were new concepts, though we did call it the Subjective Story before we changed it to MC vs. IC throughline – a label easier to understand but one that led to inaccurate interpretations. That’s why I/we changed it to Relationship Story in the third iteration.

An Objective view of the conflict between us (plot) juxtaposed against a Subjective view of the conflict between us (relationships). This is how a story works. It’s a model of how we think—not how we believe others think.

The more one sees the throughlines as perspectives, and one removes the ‘character’ from the throughline labels, the closer you get to a true understanding of them.

The Relationship Story Throughline is not about two characters arguing—it’s about a perspective of conflict available to us when approaching the inequities we find in our lives.

Relationship Players can maintain that perspective all by themselves, or they can hand it off to other couples for further exploration. In the end, the Audience compares and contrasts perspectives, not characters. The actual Players themselves fall by the wayside, allowing a greater appreciation of the meaning of the narrative.

Writing a Relationship that Counts towards a Premise

Balancing the objective with subjectivity.

While the heart of a story often feels good and sometimes brings tears to your eyes, the purpose it plays within the context of a narrative proves to be something much more meaningful. This emotional center, portrayed by the intimate bond between two characters, serves as a subjective balance to the more objectified concerns and issues of the central plot. Capturing the essence of this relationship rounds out a narrative and gives the Audience a sense of fulfillment that works with the satisfaction of a complete story.

This series of articles on The Relationship Story: The Missing Piece of Narrative explores a revolutionary new way to appreciate the Dramatica theory of story. As covered in previous chapters, the theory’s first two decades cast the Relationship Story Throughline as the meeting place between the Main Character and the Obstacle Character. Once even referred to as the Main vs. Obstacle Character Throughline, this reductive understanding shackled Authors to a limited perspective of the emotional center of their stories.

Now, we know better.

We see clearer.

The Relationship Story Throughline is a perspective, every bit as mobile as the Obstacle Character or Objective Story Throughlines. It passes from one relationship to the next, cluing Authors into the level of freedom they possess when it comes to maintaining the integrity of their narratives.

As long as those Relationships explore the same thematic material.

The Development of a New Understanding

This most recent development in the understanding of the Dramatica theory of story began as it always does: with a conversation about a film.

John Dusenberry, a student of mine when I taught at the California Institute of the Arts, now does a ton of work behind the scenes to help develop our app, Subtxt. If you’ve read the Storybeat Breakdown of Back to the Future or enjoyed the detailed analysis of The X-Files episode Milagro, you know his work.

John loves Back to the Future—so much so that he couldn’t line up his love of the film with the official storyform. Why was Beating the space-time continuum seen as the Goal of the story? And why was the father/son relationship between George and Marty elevated in importance, when clearly the “heart” of the story was the friendship between Doc and Marty?

Their very friendship hangs in the balance over whether [or] not doc will give [in] and want to know about the future, right?

Of course, knowing what I assumed to be correct at the time—that the Relationship Story Throughline was always between the Main Character and Obstacle Character—I gently led him to a better appreciation of the film...

...in a chat conversation that lasted almost an entire week.

John wouldn’t let up, and thankfully so, because honestly—this series of articles and this more significant appreciation of relationships would not be here if it weren’t for his persistence.

This was the moment it all became clear to me:

Hmmmmmm.. Is it possible that the RS doesn’t just apply to one person in every story, but can be seen as split up between several people that the main character has a “relationship “with?

Something about that sounded right, almost as if it contained traces of our understanding of Obstacle Character hand-offs, but I wasn’t entirely sure...

Isn’t the relationship with Marty and Lorraine also about temptation?

And that’s when it all locked into place.

Moving from a place of temptation (having the hots for him) to the conscience place of, as she says, “this is all wrong”

With temptation and conscience, John refers to the Relationship Story Problem of Temptation and the Relationship Story Solution of Conscience—key thematic Storypoints needed to balance out Back to the Future’s premise. Previous analyses only saw these Elements in light of the father/son relationship, but it makes even more sense here—if not a bit creepy in nature—as it applies quite accurately to the mother/son relationship.

And as it turns out—it works just as well for Doc and Marty’s friendship.

The Balance of a Story

If a complete story is truly an analogy towards a single human mind trying to resolve an inequity, then it would only make sense that that mind would want to sample that inequity from all sides. As we discovered in an earlier article Separating the Relationship from the Individuals in a Relationship, the Four Throughlines in a story represent the four different perspectives available to our mind.

We can never be sure if inequity is what it seems, so we need these perspectives to help us triangulate (quadrangulate) our perception with reality.

I. You. We. They.

The Relationship Story (We) balances out the Objective Story plot (They) in the same way that the Obstacle Character (You) balances out the Main Character’s concerns and issues (I).

The Unspoken Inequity at the Center

Stories find motivation in a single inequity—an imbalance that is impossible to describe directly. That’s why we create a story to explain it.

By definition, inequity is the imbalance between things, not the things themselves, and the only way to honestly describe that space is to approximate it by sampling this disparity from all sides.

In Back to the Future, that inequity appears as an Element of Avoidance from the Objective Story perspective. The terrorists seek revenge on Doc. Marty chases getting his parents back together. Biff pursues Lorraine.

That inequity also looks like Avoidance from George’s Obstacle Character point-of-view. His inability and refusal to pursue Lorraine creates an enormous amount of conflict for those around him.

It’s when we start to look at the remaining points-of-view, the Main Character and Relationship Story, that we begin to get a better idea of what the inequity in Back to the Future is all about.

From Marty’s Main Character perspective, that inequity at the heart of the story looks like an Element of Hinder. The principal tells him he’ll never make it anywhere, no one wants to hear his band, and everyone and everything else basically stands in his way and hinders him from living the life he wants to lead. This Element packs a ton of motivation into Marty’s Throughline.

The Relationship Story Throughline brings it all full circle (square) with an entirely different look at conflict. An inequity that looks like Avoidance from the You and They perspectives, and Hinder from the I perspective, must be balanced out by appearing as Temptation from the We perspective. No other Element would compliment and finish off the narrative in a way that feels balanced and whole as much as Temptation.

And it just so happens that Back to the Future finds not one, but three different relationships to illustrate this essential Element.

Sharing Thematic Elements

A brief look at the storyform for Back to the Future reveals these key Storypoints for the Relationship Story Throughline:

- RS Throughline: Psychology

- RS Concern: Relationship Story Concern of Becoming

- RS Issue: Commitment

- RS Problem: Temptation

While these Storypoints possess unique names like Concern and Issue, know that in the final result they’re all problems—just seen at different resolutions. The Problem is the most discrete and most delicate resolution, the Throughline is the broadest and most general. Understanding Dramatica’s Complex Terminology Made Easier makes this easier to understand.

For a relationship to count towards the balance of the narrative in Back to the Future it must exhibit one, or several, of these Storypoints throughout the story.

All three relationships feature all four Storypoints.

For the Kinship relationship between Marty and his father George, the one that moves from technically related to family, the Psychological dysfunction can be found in the opening scenes where Marty contends with George’s affable fatherhood. The incompatible natures of both force their relationship into several different transformations (Becoming), from friendship to mentorship to paternal. The Issue of Commitment plays out with their refusal to give up on one another. And the Problem of Temptation balances George’s always taking the easy way out when it comes to being a father with Marty’s preference to rush in and fix things.

The Friendship relationship between Doc and Marty explores the same thematic material but in its own unique and fun way. At the outset, their friendship is one of playful dysfunction, both in the present day and when they meet back up in the past. Transforming from partners to friends and avoiding the devastating transformational effects their friendship could have on the space-time continuum illustrates their relationship’s concern with Becoming. Being friends with someone who clearly needs to be committed takes an equal amount of dedication and tenacity, thereby fulfilling the Storypoint of Commitment. And that Temptation to take the easy way out, to tell a friend the truth regardless of consequences threatens not only their relationship but also their very existence.

And then finally, the reason Disney initially passed on Back to the Future: the relationship between mother and son. Dysfunctional to the core and contentious in its attempts to become something it should not satisfy Psychology, Becoming, and Temptation all in one fell swoop.

But what about Commitment?

The Meaning is the Message

You could conceivably find a way to justify the Issue of Commitment as showing up in the mother/son relationship, or you could realize—it doesn’t matter.

The tapestry of the hologram that is the storyform interlaces meaning in the minds of the Audience, not specific Storypoints. The storyform isn’t crucial to the viewer, instead, what it represents is paramount. If a story clearly covers key Storypoints in other relationships, as it does here with Back to the Future, then the integrity of meaning will remain intact.

One could conceivably choose a single Storypoint from the Relationship Story Throughline to show in four different relationships and still honor the fabric of intention. The gestalt of the relationships between these Storypoints is all that matters. That’s why you can easily hand them off from one to the other.

So, it’s OK that the relationship between mother and son in Back to the Future dials back Commitment—the other two relationships pick up the slack, Creating in the minds of an Audience a seamless whole.

When It All Adds Up

Appreciating the real intention of narrative requires one to separate themselves from notions of characters as real people and of plot-lines, or Throughlines, serving these characters. Instead, these characters and plots work under the employ of the story’s meaning—of its ultimate premise.

Creating a relationship that matters requires an understanding of the kind of conflict needed to balance out a story’s thematic exploration. By touching upon key Elements, the Author signifies that this relationship matters—pay attention because it counts towards what I’m saying with my work.

Ignore this connective tissue, and you risk writing something insignificant—a throughline or relationship that might touch upon other areas of the narrative, but not the heartfelt emotional core at the center of it all.