The Effect of Premise on Narrative Structure

Encoding meaning into the order of events.

What you want to say with your story determines what you write. It seems simple enough—until you realize that the order in which those events appear in your story carries significance. Suddenly, your purpose becomes more than a reason to get out of bed in the morning. What you want to say, your Premise, orders your thoughts into a unique and meaningful narrative structure.

In On the Art of Dramatic Writing, Lajos Egris identifies the Premise of Shakespeare’s Macbeth to be “Ruthless ambition leads to self-destruction.” Othello’s Premise is “Jealousy destroys itself and the object of its love.” And while he champions the Premise as the basis for all grand narrative, Egris also recognizes that it’s only a start:

The Premise contains all that is required...character, conflict, and conclusion. What is wrong, then? What is missing? The author’s conviction is missing. Until he takes sides, there is no play. Only when he champions one side of the issue does the premise spring to life.

It wasn’t until fifty years later, and the introduction of the Dramatica theory of story, that we finally found the nature of that conviction.

But it requires us to make a choice.

When I read the Dramatica manual, they always seem to fall into dualistic thinking: is your story a success or failure? Does it have good judgement or bad judgement? Who wins the thematic argument, IC or MC? Problem vs. solution, one vs. the other. So right now, to me it seems that Dramatica wants you to take a side. Or am I interpreting the manual falsely?

Yes, Dramatica wants you to take a side. The same way Egris recommends taking a side.

The same way your Audience expects you to make a choice.

If you don’t take a side, then no one will have any idea what it is you’re trying to say. Your Audience won’t bother with your story.

If ambiguity is your purpose, then argue the success or failure of not knowing the truth. Inception did. Cobb’s turning away from the top signals the success of choosing one’s perception over reality. It doesn’t matter whether or not he continues to dream—he wanted himself, and that was an argument for success.

The outcome of a story is not a black and white event. There are degrees to success and failure, and there exists an emotional component in the form of the Story Judgment. Also, Story Costs and Story Dividends help balance out the seemingly heavy hand of the Story Outcome.

But you need to say something.

The Dynamics of a Narrative

When setting the stage for a narrative argument, an Author addresses eight key dynamic questions. By dynamic, we mean to establish the forces of energy working through the narrative structure—not the structure itself.

One such dynamic is the question of whether or not the story ends in Success or Failure. This Story Outcome focuses the Audience on a key fundamental of the Author’s Premise. Is he seeking to make an argument as to why things fail? Or is he writing about the kind of approach needed to ensure success?

Consider the Premise of Casablanca:

You can secure freedom for others when you give up restraining yourself.

The film specifically argues what it takes to achieve freedom for those around you successfully. Give up controlling everything, and you can win.

What would that same story look like if the Premise focused on Failure?

Seeing the Other Side

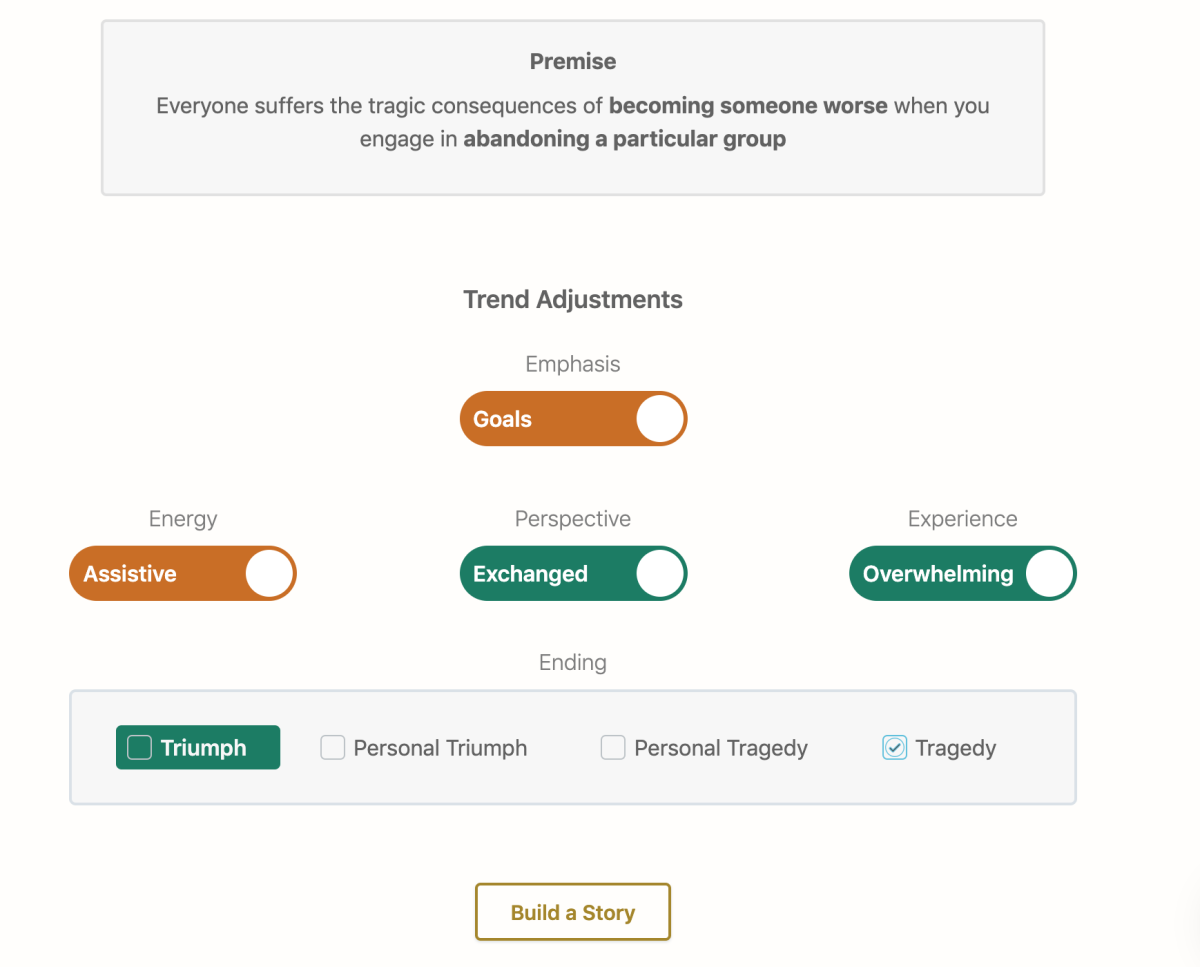

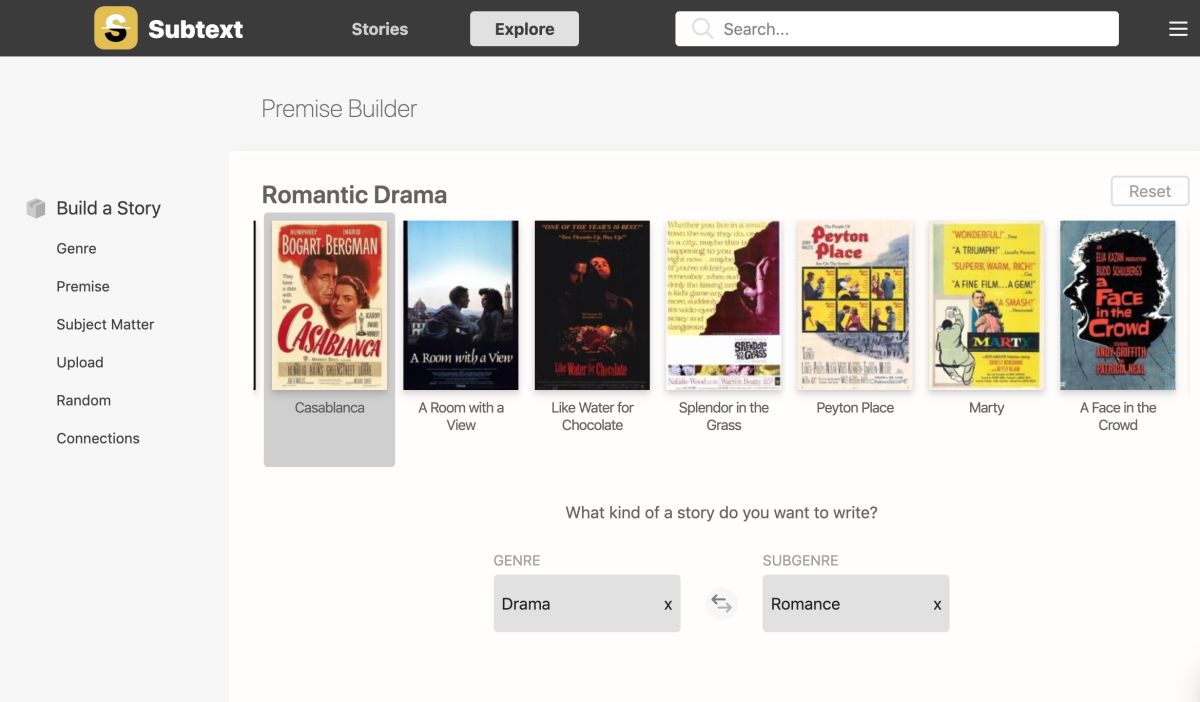

Open up Subtxt, click on Premise, and then search for Casablanca.

When you select the film as a single storyform, scroll down past the Premise until you reach the Adjustments section. There, you’ll find a box labeled Meaningful Ending and a checkmark next to Triumph.

Click on Tragedy, and watch what happens to the Premise when the dynamic shifts from Success to Failure:

Everyone suffers the tragic consequences of becoming a Nazi when you give up living free.[^premise]

[^premise]: Your premise in Subtxt may differ from this example. While the superficial Storytelling may be something other than "becoming a Nazi" or "living free", the base Elements of Becoming and Freedom (Free) will remain the same.

Do you see the difference?

More importantly, do you feel the difference?

Sure, it may appear as if they’re two sides of the same coin—that they make the same argument, just from two different points-of-view.

But they’re not the same argument.

The original proves for Success. The latter for Failure. In the first, giving up living free doesn’t even factor into it—save for some lip service paid to help strengthen the argument. The latter is all about living free.

Playing the Ends of an Inequity

Remember Rick's spurned ex-lover, Yvonne (Madeleine LeBeau), in Casablanca? She was a stand-out example of the consequence found when giving up one’s freedom. Consorting with the enemy painted her as a traitorous tramp, and she paid the price with humiliation.

But the film didn’t make an argument about her humiliation. Her brief moment was a signal of the consequence of living under Nazi rule, not of giving up one’s freedom. While that may sound like the same thing, the subtle contrast makes all the difference when it comes to writing a story.

Living under Nazi rule is a problem of Control.

Giving up one’s freedom is a problem of Freedom.

Two completely different stories.

Control and Freedom[^update] sit at two opposite poles of inequity within the Dramatica Table of Story Elements. As such, they function as solutions for each other. Freedom is the solution for an over-abundance of Control, Control is a solution for a complete lack of Freedom. Casablanca as is portrays the first relationship of conflict; our imagined Failure story with Yvonne front and center takes the second.

[^update]: The original version of Dramatica identified the dynamic pair of Control to be Free. A more accurate interpretation of this Element would be Free (Freedom), and will be reflected in a later version of Subtxt.

For the latter, consider a scenario where Yvonne saves the day by taking control of her life and the city she loves. She takes over Rick’s cafe, kicks out the remaining Nazi sympathizers, and sets boundaries for any further foreign invaders.

It sounds like an analogy for her personal issue with boundaries, right?

Totally different story. Totally different direction when going from Problem to Solution. Casablanca moves from Control to Freedom, Yvonne’s Revenge moves from Freedom to Control.

That difference in direction makes all the difference when it comes to laying out the structure of the story.

But that’s not even the story we were trying to tell.

The Meaning of Failure

Note how easily I slipped into the assumption of Success. Yvonne takes over and takes back Casablanca. That’s what happens when you move from a Problem to a Solution.

Our Premise, however, was about the Failure of giving up Freedom:

Everyone suffers the tragic consequences of becoming a Nazi when you give up living free.

In a Failure story, you never quite reach the Solution; failure comes as a consequence of being overwhelmed by the Problem. Those consequences of becoming a Nazi happen when you give up the Solution of Freedom—not the Problem of Freedom. Huge difference.

The proper Premise for Yvonne’s Revenge would be:

You can win back your own sovereignty when you give up abdicating your freedom.

She solves her problem of a lack of freedom by directing her efforts in a concerted effort. That would be a Success story.

Signaling the Purpose of Your Story

Casablanca doesn’t unequivocally say that Yvonne becomes a Nazi sympathizer. We might infer that outcome, but we’re never told the result of her actions explicitly. If we had followed her story and taken it to the extremes, then yes, we would make an argument worthy of the Failure Premise.

But we stayed with Rick.

The purpose of the story was not to focus on the consequence. Instead, Casablanca portrays the successful achievement of the Goal. And Rick’s giving up personal restraint wins freedom for the good guys.

The Author’s conviction that giving up control leads to success plays out in the final film.

Your selection of Success or Failure clues the Audience in on the message, or point, of your story. Are you saying that this approach definitely leads to success? Or are you saying that this way leads to failure?

This choice is essential, as it sets the specific areas of conflict in each Act.

Meaningful Plot Progression

Objectively, Casablanca is an exploration of physical conflict. Refugees seek visas, couriers make backroom deals, the local police trade freedom for sexual favors, and Nazi soldiers shoot libertines dead in the street.

Conflict bred from Physics falls into four general areas:

A story feels complete when it addresses all four areas of its objective conflict.

The order in which a story proceeds through these areas finds influence in several crucial dynamics—the most important being the Story Outcome of Success or Failure.

If the Goal of a story is a location on a map, then the narrative structure is the path from where you stand to the end. Success heads one way, Failure the other.

Casablanca as a Success story takes on this plot progression:

- Learning

- Understanding

- Doing

- Obtaining

Feels successful, right?

In the first Act, everyone tries to Learn the location of the stolen visas, while Ugarte and Rick keep it a secret. Rick’s refusal to stick his neck out for anyone leads to Ugarte’s death, beginning the 2nd Act campaign of Nazi intimidation.

Commandant Strasser makes everyone Understand the severity of their situation by bringing them in for questioning, while Ilsa works on Rick. When that doesn’t work, she pulls a gun on her former lover—threatening to Do him in if he doesn’t hand over the visas.

Rick’s decision to help Lazlo escape signals the start of the 3rd Act, and a shift into the final context of conflict, Obtaining. Lazlo and Ilsa secure a plane to freedom, while Rick and escape Nazi rule.

The structure of a narrative communicates intent. This path of Learning to Understanding to Doing to Obtaining is equivalent to Success within the mind. The reason the Audience equates the ending with triumph lies in recognition of this pattern.

The Path Not Taken

The Failure version of Casablanca not only heads in the opposite direction—it takes an entirely new path altogether:

- Obtaining

- Learning

- Understanding

- Doing

Sounds outright depressing to me.

Even just saying those words in that order, without context, feels like things are headed in the wrong direction.

In the 1st Act, Yvonne and her compatriots start things out by abdicating their liberty—handing over their freedom to the Nazis, who gleefully Obtain their allegiance.

Rick decides to hide the letters of transit at the start of the 2nd act, forcing Yvonne and the others to Learn what it takes to keep Nazi invaders happy and peaceful (told you it looked grim). When that doesn’t work, and Rick seems more interested in this beautiful new arrival than the plight of his friends, Yvonne goes all-in with her Nazi boyfriend. Her mis-Understanding sets the stage for the same scene to play out where the locals call her out in front of everyone—only this time, we appreciate and understand the meaning behind her actions.

Everyone suffers the tragic consequences of becoming a Nazi sympathizer when you give up living free.

Misunderstanding Rick’s intentions was just another step down that path of giving up personal freedoms.

When Yvonne overhears Rick’s conversation with Lazlo and his decision to leave with Ilsa, the only thing left for her to Do is help her Nazi overlords.

The 3rd Act plays out as it did in the original film, only this time we see it from Yvonne's point-of-view as she helps the Commandant and Renault set a trap for Rick and Lazlo.

Yvonne and Renault arrive just in time to thwart the escape. Rick pulls a gun on Renault, and orders Ilsa to board the plane with Lazlo. Strasser arrives just in time to see the leader of the French resistance taxi into position for freedom. The Commandant dashes for the phone and makes the call—

BLAM!!

Strasser turns to see Rick crumple to the tarmac lifeless, Yvonne standing behind him, pistol smoking.

“Welcome to Casablanca, Herr Strasser,” she tells him.

Renault stops the plane, takes the pistol from Yvonne, and reluctantly suggests something about pinning his friend’s death on Lazlo. “The usual suspect will do fine in this case.”

Yvonne takes control of the situation by giving up the last remnants of her freedom. She transforms the face of Casablanca, and possibly the course of the war, sealing our imaginary Yvonne’s Revenge in abject tragedy.

The Purpose Behind a Premise

The Premise of a story is more than merely what you want to say—it’s code for how to structure what it is you want to say.

Triumphs dictate one path; tragedies another.

If you’re unsure of the purpose of your story, or what it is you want to say, your path will meander, and you will eventually get lost.

Many refer to this uncertainty as writer’s block.

The Premise exists to keep an Author on course, or at the very least, give her a direction to find a course while she writes her story.

The dynamic questions of a Premise identified by Dramatica frame Author’s Intent. They force you to become intimate with your subconscious impulse to express yourself through a story. No more hiding behind “writer’s block.” No more fishing aimlessly for an answer because you’re not sure.

Get real with yourself.

What is it you want to say with your story?

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.