The Magic of the Storyform

Unveiling the unknown: where storytelling meets magic

Rare is the opportunity for us nowadays to experience something truly wondrous. Sure, we might witness the birth of our own child or watch with bated breath as a satellite a billion miles away navigates its way through the rings of Saturn. But what about story?

If there is one quality that propels the Dramatica theory of story above all other paradigms it is that it can predict certain parts of a story. The program is smart enough to take the choices an Author makes about what it is they want to say with their story and give back to them parts of their story they hadn't even considered. The effect is pure magic. Things unknown about a story become known, revealing parts essential for the story to feel full, complete and meaningful.

Kurt Vonnegut, the writer behind Slaughterhouse Five, may have taken issue with computers and their efforts at "graphing" storytelling, but chances are he never had a chance to see Dramatica in action. Even if he did, he probably would have hated its accuracy in predicting some of the choices he made. How could a computer possibly mimic the intellect of a great writer? His disdain for such applications may have inhibited the wheels of progress for some time, but then, bruised egos often can't help themselves.

We are learning at an exponential rate how our minds work. The Dramatica theory of story is simply one aspect of that research and a fascinating insight into why some stories work better than others. The best way to witness this uncanny feature or predictability in action is to answer the program's questions about a great story that already works, and see if what the application predicts fits the work in question.

Steadfast Characters and Their Problem

Before diving into the specific examples, it becomes important to understand the nature of a Steadfast Character and the Problem at the core of their Throughline. With Change characters, the Problem works as expected: it identifies the source of trouble in their life and the matching Solution signifies where their change will lead them. With Steadfast characters the Solution never comes fully into play (it will in small doses throughout a balanced story, but never like the Change character), their Problem will appear to be more like the source of their drive rather than a true problem. It will define them, almost like a core characteristic. By looking at the Steadfast character's Problem within these examples, one can get a sense of Dramatica's magical ability to predict elements of a story.

What is a Storyform?

For those unfamiliar with Dramatica, a storyform describes the unique collection of thematic dynamics and story points that communicate the meaning of a story. In the present incarnation of the program, there are 32,768 possible storyforms. The process of storyforming needs an Author to make structural choices about their work in order to narrow down that broad number to the one unique set of appreciations that matches what it is they want to say.

When analyzing a work through Dramatica, the analyst tries to discover the one storyform that best matches the story in question. They begin with the most easily-identifiable story points, slowly working their way to the less obvious until they get down to the one storyform. When that happens the storyform will magically "sing", predicting story points and thematic elements that the analyst did not provide. That's the moment when the analyst knows they've hit upon the right one.

And that's the moment we'll be looking for in these examples.

Star Trek

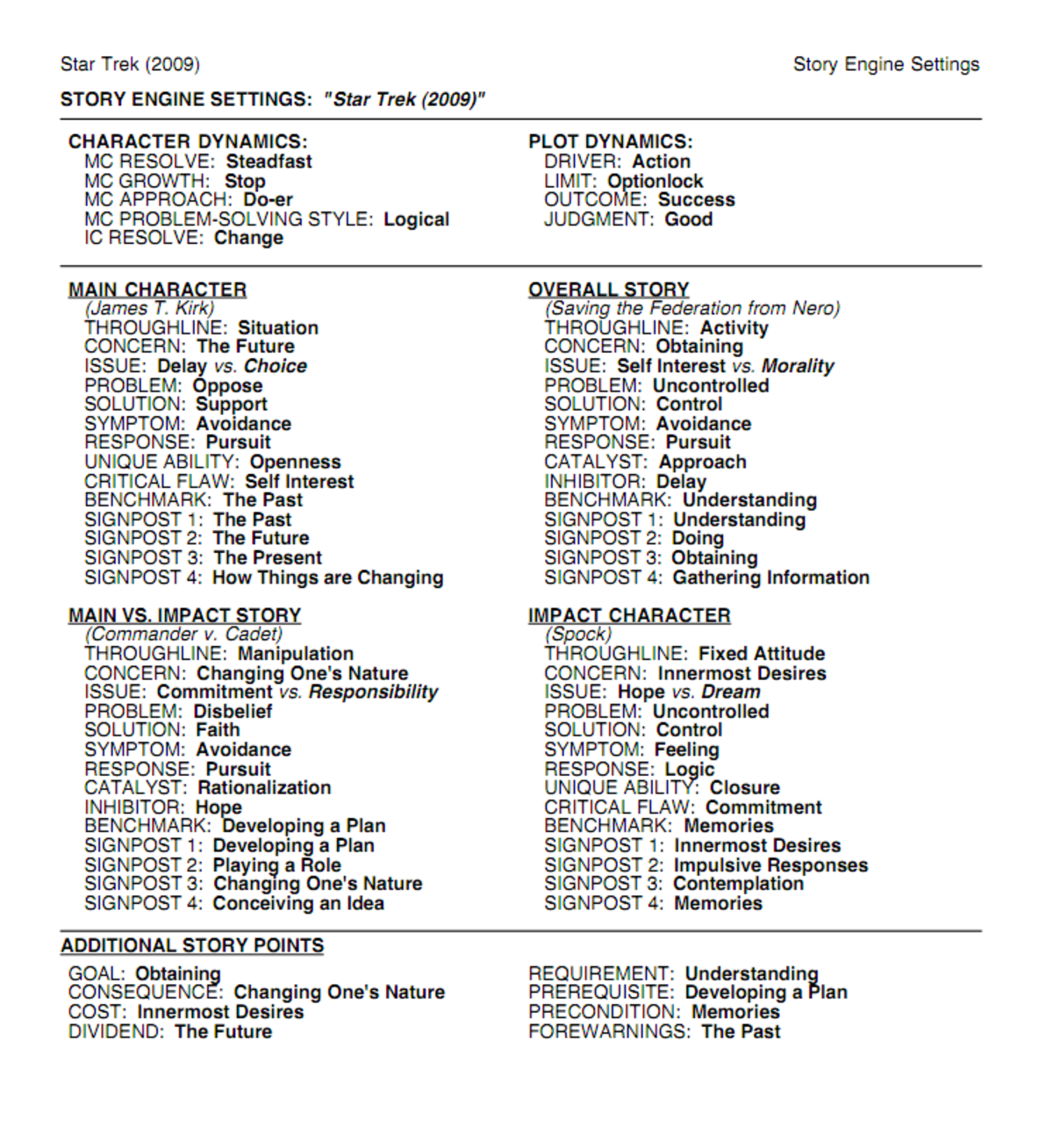

J. J. Abrams' sci-fi lens-flare spectacular offers audiences a solid, well-illustrated storyform. Starting with Kirk's Main Character Resolve of Steadfast (and Spock's Resolve of Change), the Captain's Approach of Do-er and Male Problem-Solving Style seem most obvious. So too do the Story Dynamics of Action Driver, Spacetime, Story Outcome of Success and Story Judgment of Good (a Triumphant ending).

The Objective Story, with its chases and space battles, fits nicely in the Domain of Activity, as does Kirk's personal Main Character Domain of Universe (the ne'er-do-well son of a hero). This forces Spock's Obstacle Character Domain into Mind--and our first glimpse at the magic in action. Mind describes Spock's Throughline perfectly: a Vulcan fixated on the rational. The Relationship between the two falls into Psychology, meaning their battleground centers around conflicting ways of thinking. Once again--magic. A perfect way to describe the conflict in their contentious relationship. They each have different ways of thinking how best to solve the problem at hand, both trying to manipulate the other into seeing things their way.

Here, things become less obvious. Certainly the Objective Story Concern must be Obtaining, particularly in a story about revenge, but beyond that is the story exploring an Issue of Self-Interest, Altruism, Approach or Attitude? Perhaps Spock's Throughline would offer an easier way into the storyform.

Stepping down into the Mind Domain and a Concern of Subconscious (what drives him!) we find four groups of four elements each. Scanning the four for the best grouping, the quad below Hope sings out the name Spock: Logic, Feeling, Control and Free. If ever there was a group that described what problems a Vulcan goes through, this would be it!

The question now becomes, which one is his Problem? What is the true source of his inequity? It's clear that he believes his emotions get the best of him, a Focus of Feeling seems to be the best choice as the Focus describes what a character thinks their problem is.

And with that, we're down to one storyform. And here is where the magic begins.

The program has identified Spock's Problem as Free and his Solution as Control. Think to his fistfights with the young Vulcans earlier on in the film for an example of his Problem, and his ability to control his emotions at the end for proof of his Solution. Hopping up to the Objective Story we see that the program has identified Free as the Objective Story Problem as well (Nero anyone?) with Avoidance as the Focus (warp-holing to prevent things from happening) and Pursuit as the Direction (pursuing Nero to the ends of the universe). So far so good.

But the greatest instance of magic, the one that solidly identifies this particular storyform as being the one, is in Kirk's Domain. Based on the choices made, Dramatica predicts that Kirk's Problem would be Oppose. How could one possibly find a better term to describe him in this story? Not only does this trait show up in the opening scene where he borrows his step-dad's car, but also in every other scene where someone tells Kirk he can't do something. When people Oppose Kirk, he goes after them (MC Direction - Pursuit--more magic!).

Without any tampering from the analyst, Dramatica has accurately predicted the types of thematic elements that would make Star Trek work as a solid story. If one were looking to write this story within the first couple months of development, a simple adherence to the suggestions made by the program would help guarantee the final product would mean something - that everything would together in a seamless holistic piece.

But what about something a little less popcorn-predictable? Maybe something more scholarly, more character-driven?

Jane Eyre

No way a computer program can predict the intricacies of Charlotte Brontë's 1847 novel, right? Well, if you plug in Jane's obvious Resolve of Change, her Approach as a Do-er, her Holistic Mindset (how else to explain her new home in the middle of nowhere?), and the Story Dynamics of Decision, Spacetime, Success and Good, the storyform begins to take shape.

Add to this an Objective Story clearly set in Psychology (conflict stemming from the myriad of characters who have designs on Jane) and an Objective Concern of Becoming (again, manipulating Jane to become what they want) and the program has narrowed down the possible storyforms to 16. One of those sixteen elements must be the Objective Story Condition--the condition plaguing everyone within the story.[^condition] As with the analysis of Spock, we group the four quads of four as a group in order to figure out which set feels more like the source of trouble within the story. Realizing that everyone creates trouble for themselves when they act from a sense of Obligation, an analyst could easily see how Logic, Feeling, Help and Hinder "sing" the nature of difficulty within this story. In fact, doing what is sensible (Logic) screams out as the actual Problem, particularly in light of Jane's final decision to go with her emotions instead (Feeling).

[^condition]: The Objective Story Condition is part of a new development in Dramatica theory surrounding the Holistic Mindset. The Holistic Mind sees inequity as a Condition moreso than a Problem.

But where is the magic?

Hop on over to Rochester's Obstacle Character Domain (Mind (a fixed attitude)--how about that for starters?) and one can see how the program has predicted his Problem to be Conscience. How else would you describe a man who cares for a wife who so clearly belongs in a mental institution? Is that not doing the right thing, rather than taking the easy way out? Amazing, right? A computer program has accurately predicted the choices a mid-19th century author made during the writing of her novel.

Magic. Pure and simple.

The Enduring Model of the Mind

The reason Brontë's novel has lasted for nearly 200 years and the reason why people still feel compelled to retell that story is because it based its narrative on a solid storyform. Storyforms are simply models of human psychology--a snapshot of the human mind at work trying to solve a problem. Audiences recognize this fact and appreciate the care given to a story that thinks the way they do. They feel drawn to stories that have something meaningful to say.

So does one need this program in order to create something as powerful and lasting as Jane Eyre? Dramatica co-creator Chris Huntley had this to say:

The theory is a discovery more than an invention. The software is an invention based on the discovery.

These principles of story structure were there long before the invention of the computer and the programs that followed it. So no, by trusting their instinct, an Author could conceivably create something enduring and everlasting. The theory is a discovery of the process of acquiring meaning already within us. The invention of the application Dramatica simply offers us the opportunity to see that magical process in action.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.