The Sound of Music Making History Meaningful

Weaving the von Trapp familys escape into a purposeful narrative

Some Authors find themselves inspired by a bit of character, a few lines of dialogue, or a genre that they themselves wish they could explore. Others find their muse within the real life actions of those who overcame insurmountable odds.

The latter describes the motivation that led to The Sound of Music. Inspired by the historical escape of the von Trapp family from Nazi encroachment at the dawn of World War II, Ernest Lehman (from a book by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse) endeavored to give meaning to that Austrian family's life story.

No easy task, mind you, especially in light of the fact that life can have several meanings depending on how one looks at it. Deciding how to frame historical events, what to leave out and what to emphasize, becomes the tenuous task of the purposeful writer. Sometimes, in the effort to capture it all, one ends up creating a long, involved final work.

Why the Film Is so Damn Long

Why is that so many people turn the TV off once the Captain and Maria get married? Are audience members that insensitive to the plight of Austrians under Nazi rule or do they simply have better things to do? Could there be a more interesting structural explanation for this all too common behavior?

Turns out people aren't that heartless--they're simply more interested in the first story, rather than the second.

The Complete Story Unit

What does it mean when someone refers to a complete story? Aren't all stories equally complete when the Author puts the pen down?

No.

When speaking of completeness in the context of story structure, one refers to a piece of narrative fiction that looks at the story's central problem from every angle. This is how a story becomes more than simply a telling of events: by allowing an audience member to experience the efforts to solve a problem both objectively and subjectively at the same time, a work of fiction creates meaning. We can't do this in real life. Sorry to say, but life has no meaning unless we create some objective context within which to appreciate it (religion, politics, story structure, etc.). To be perfectly accurate, said objective context is only subjective as we can never know what is going on...but such matters are probably best served elsewhere. Suffice it to say, complete stories deliver an experience of meaning...but only if they cover every viewpoint.

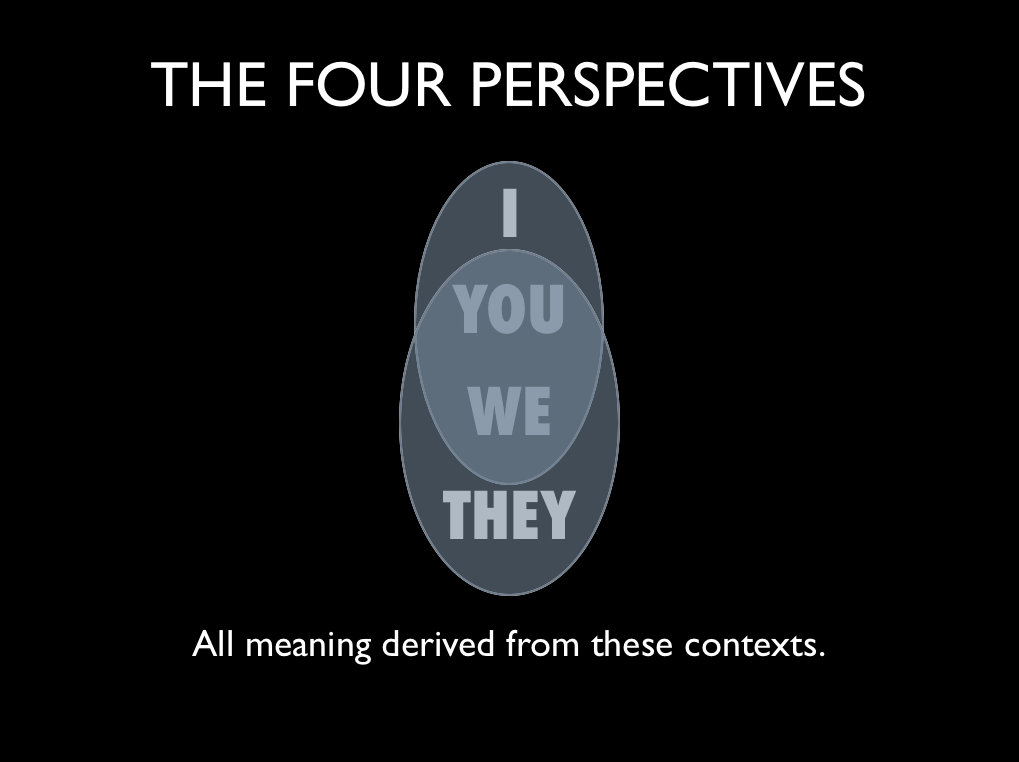

There are four contexts with which one can look at a problem: I, You, We, and They. Those four cover every angle. Those four cover a problem completely. And those four are the only four. Our present understanding of the universe does not allow for anymore.

A story examines these four perspectives through four throughlines: the Objective Story Throughline, the Main Character Throughline, The Relationship Throughline and the Obstacle Character Throughline. The correlation between these throughlines and the perspectives they take should be obvious. The Main Character represents the I perspective, the Objective Story takes the objective They perspective and so on. The Relationship Throughline takes a look at the problem between the Main Character and the Obstacle Character, as in We have a problem.

For a story to be complete, for the problem to be throughly examined, a work of meaningful fiction must have all four throughlines and must have them throughout the entire "story". Kung Fu Panda 2 abandoned its Relationship Throughline (between Po and Tigress) halfway through. That is why the film feels broken in two. The Nightmare Before Christmas didn't even get that far. Jack and Sally have their own throughlines but never fully develop a relationship--which is why that film feels so cold.

The Sound of Music, on the other hand, had so much to say about what happened that they created two complete stories in one work.

Making the von Trapp Family

The first story covers the area most people cherish and remember: the romance and eventual wedding between Maria (Julie Andrews) and the Captain (Christopher Plummer). The romance takes care of the Relationship Throughline, or the We perspective. The conflict between the two grows from the disparity between how each thinks. They know how they feel about each other, or at least can sense it, but how to make it all work becomes an entirely different matter.

The wedding, on the other hand, takes care of the Objective Story Throughline, answering the question: what do we have to do to make the von Trapp family whole again? Because this throughline represents the perspective of They, it covers a more objectified look at the characters. Instead of the heartfelt romance, here we see the commandant father, the chaotic kids, the governess, the baroness and so on. Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer as players fulfill roles in both the Relationship Throughline and this more objectified Objective Story Throughline. Seeing both throughlines at the same time speaks to that ability of a story to manifest meaning from the objective and subjective.

If their romantic relationship encompasses the heart of this first story, then it only follows that one of them will be the Main Character and the other the Obstacle Character. Clearly Maria represents the audience's eyes into the story, with the strict rules-oriented Captain as the Obstacle Character. Maria's personal problems center around her status in life--is she a nun or isn't she? The Captain has issues of his own surrounding his former wife--can he forget his love once and for all, or is he to be always reminded of what she was like and how happy his family used to be?

This last throughline tells of the genius behind the Authors of this piece. That bittersweet song the Captain sings during the final concert, the song of the Austria he remembers and will always remember ("Edelweiss"), resonates so strongly because it is a bridge between the first story and the second. Reminded of how happy his family once was, the Captain carries this over into his realization that he is losing his bigger "family", his country. The first story ended in Triumph, the family came together and Maria found peace beyond the sisterhood. But that song feels bittersweet and not at all triumphant for a reason, and that reason has everything to do with how the other story comes to a conclusion.

The Rise of the Nazis

Ooohhhh, sounds scary. But that is what the second story is all about. Instead of taking an objectified look at the efforts to create a family, this story takes an objectified look at how the characters deal with the rise of Nazism. They deal with a specific mindset, one based on certain expectations as to how one should act. The Captain sits at the center of this conflict. Maria was the Protagonist in the first story--driving the efforts to make the von Trapps whole again. The Captain is the Protagonist in the second story--trying to stop his country's knee-jerk response into fascism. The bittersweet feeling that comes at the end comes as a direct result of his failing as a Protagonist, the Nazis take Austria.

But he isn't the Main Character of this second story.

Instead, one need only look to Liesl, and her budding romance with Rolfe for the heart of this second story. Here, Liesl fulfills the Main Character role and the strapping young lad takes over the role as Obstacle Character. Their love story parallels the more adult romance in the first story, both in structure and in song, yet finds itself dissolving into a far more tragic ending.

The Importance of the Second Story

The story of the von Trapp family is an historical one. As mentioned before, real life events unfortunately don't have meaning. That's why we have Authors. In order for the entirety of the von Trapp story to unfold and to unfold well, this second story needing crafting. To continue on after the wedding, as they did in real life, without an actual story to support it would have secured The Sound of Music's place in film history right beside You've Got Mail or the countless other forgettable films that end their stories 30-45 minutes before the credits start to roll. The von Trapp's ascent into the Alps would have been a yawn-fest.

Luckily for us, the Authors knew the importance of a complete story.

Weaving Two Stories Together

Again, addressing the relative talent and genius of these Authors, this second, more dramatic story, does not simply begin when the first ends. Instead it weaves its way into the first, like a fine tapestry of meaning, inserting little tidbits of the story to come. From there it is the first story that occasionally makes its presence known, tidying up any loose threads and offering any meaningful commentary (such as the Captain's song) on the events that unfold.

While handing off the reigns of problem-solving from the first to the second, the Authors were careful to make sure that they didn't infuse the wedding with a bombastic That's All, Folks! sort of moment that one finds at the end of Star Wars or Top Gun. They made sure they resolved the first inequity, but did it in such a way that the two stories, the story of the von Trapps, feel like one continuous piece.

But try as they did, they simply can't fool the human mind.

Because stories function according to the mind's problem-solving processes, when a problem loses that energy (i.e., the problem resolves) so too does the audience's interest in a work of fiction. This is why, if you're ever watching a film or TV show with children, they start to get squirmy before the credits even roll. Instinctively, their minds know the problem at hand has come to an end. They don't care who worked on it!

And this is why many abandon the von Trapps in their time of need. Sure, it's great to see them cross that mountaintop threshold, but the story most care about--the story of what to do with Maria, and the romance with the Captain, and the wedding that brings them all together--that story ended long before the curtain dropped.

Bringing meaning to the meaningless requires setting up the dynamics of a complete story. It means placing actual events within the context of the four throughlines. If one can't cover said events within one set, the work as a whole demands another story. If not, the creators risk losing their audience and diminishing the importance of the history they were so inspired by.

:: expert Advanced Story Theory for This Article The Dramatica theory of story is the only known understanding of story that calls for all four throughlines. Recently there have been some paradigms that have felt it appropriate to "adopt" these concepts without proper credit. Prior to 1994 this understanding was only instinctively known by the great writers of old. ::

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.