The Structure of a Short Story

Dramatica's truth: all stories mirror the mind's process

Story is story, regardless of length, format or delivery device. There is no specialized structure for a two-act play anymore than there is one for a Saturday morning cartoon. Assuming that the purpose of narrative fiction is to create some greater meaning that we cannot experience in our own life, the process to deliver that meaning will always be the same.

The Dramatica theory of story--the most accurate model of story available today--is based on the premise that every complete story is really an analogy for the human mind's problem-solving process. When a film or novel deviates from this process, whether it be through a missed plot progression or inconsistent character motivation, the audience instantly picks up on it because each and every one of them has their own mind. They are all intimately aware of this process. They are all experts in story.

Different Minds, Different Stories

Regardless though of the similarities between how everyone is constructed, no two human lives are exactly the same. Everyone has their own idiosyncrasies, their own way of going about things and their own take on the issues affecting them. Everyone is unique. The same can be said of complete stories.

The psychotic mind at the center of Se7en is completely different than the pop princess mind that is The Little Mermaid. Both operate under the same process and the same dynamic forces, yet their personalities and the way they go about solving problems couldn't be more different. The reason they both found success with their individual audiences is because they both honored the analogy between story and mind.

The Analogy Revealed

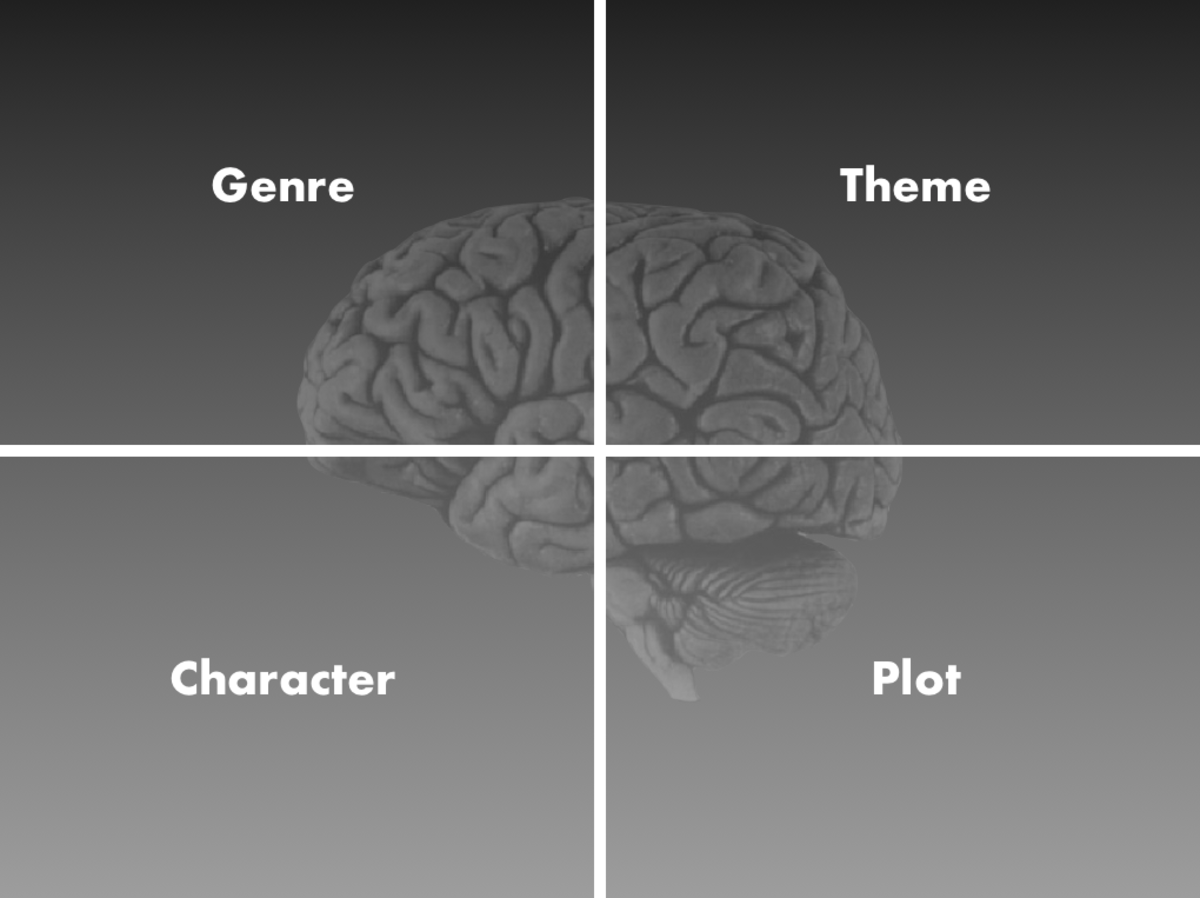

What good can come from classifying stories as an analogy to the human mind? Well, for starters, the reason why Character, Plot, Theme, and Genre ever came into existence becomes clear.

Characters were developed as a means of expressing the motivations within the human mind. Just as there are motivations within a single mind to solve a problem, delay it, or avoid it all together, so too are there characters within a story who exemplify the same motivations.

Plot came about as a natural representation of the methodologies that the human mind explores in solving problems. The various strategies and approaches taken within a story perfectly mimic the actions and reactions the mind employs.

Theme, often seen as the measuring stick with which to judge the characters and the actions they take, was developed as a need to express the evaluations the human mind undergoes. Determining whether the process is worth continuing or whether or not to trust Progress are natural processes everyone experiences in their own lives millions of times a day. In a story, Theme assumes that mechanism.

And finally, Genre was created as a way of expressing the purpose behind a mind's attempt to solve a problem. Typically Genre is viewed in light of its category on Netflix or in iTunes - Romantic Comedy, War Drama, Action/Adventure, and so on. But seen in the context of the human mind solving a problem it becomes apparent that these genres are really aiming at a specific purpose: Action/Adventures aim to entertain and delight with explosions and fast-paced editing, Period Pieces aim to inform while also exploring human relationships over the centuries. The Genre specifies the purpose.

Put together, each part combines to create a meaningful model of the human mind at work. Each part combines to create a complete story.

Slicing the Short Story

But when it comes to stories that are shorter in length, it becomes impossible to explore the whole thing. There simply isn't enough time to go down every avenue and accurately depict the entirety of the human mind at work.

But Authors can take a slice.

The key is to give the audience just enough of the taste of the "mind" of a story that they become hooked, seeing an Author as someone they can trust to give them the kind of meaning they go to stories for. Authors could simply focus on Character, insuring that the central character develops over time, growing to an eventual meaningful resolution. Or they could simply offer up a slice of Plot, constructing a story that ends meaningfully or naturally develops through four Acts. They could even cross-cut their piece, taking a bit of Character, Plot, Theme and Genre with it in an attempt to provide a glimpse of something greater just beyond.

This latter approach is taken in John August's wildly entertaining story, The Variant. In the short span of 23 pages, August delivers a combination of all four aspects of story that hints at something deeply meaningful. In essence, it is the final set piece of a potentially engaging complete story. Take for example, this one Amazon review, typical of many:

25 pages of on your edge can't wait to read next line thriller. At the end you're left with the feeling of more, I want more. Give me more John. You want the whole story, what happens next. Never any slow moving pieces to the story it all flows together seamlessly, a straight read through, you never want to put it down and come back to it, just keep going from page 1 to 25.

That desire for more, that need to fill in the rest of puzzle comes as a result of expert craftsmanship. The hints of natural character growth and a clear-cut ending that actually means something, tantalizes the human mind into desiring even more.

Another great example of this slicing occurs in Scott Frank's short story, The Flying Kreisslers. Here, Frank focuses on delivering four very clear Acts, a slice of Plot that delivers the feeling of a complete story. Because there isn't enough fictional real estate to explore every aspect of the human mind at work, Frank chooses to fixate his narrative on the Main Character's throughline, tracking the development of Ivan's journey from manipulated to manipulator. In less than 2000 words, he delivers a sense of completeness, a savory morsel that honors the mind's natural problem-solving process.

One Bite and You're Hooked

Audiences crave meaning. In the case of the short story, they want an Author to respect them by sampling just enough of that greater picture that they get the idea that there could be something greater at work here, some intelligence that more closely resembles their own. Audiences leave insulted when there is no attempt at crafting something worthwhile. If Authors wish their short stories to become cherished works they would do well to investigate how to apply the mind's problem-solving process through Character, Plot, Theme and Genre.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.