Time and Space in Dramatica: Rewriting the Story Limit

Appreciating the flow of consciousness through a story

The Dramatica theory of story is more than a cookie-cutter template of popular story structures. Dramatica is a model of psychology, an attempt (a good one) at codifying the structural elements and dynamic forces that compose consciousness. While the original conceit and intent of the theory remain solid, some story concepts require a finer tuning.

For the longest time, the Appreciation of the Story Limit escaped my concerted attention. Listen to any of the Dramatica User Group analyses over 2 1/2 decades, and you'll find me conspicuously silent in regards to the Limit.

It just didn't seem like that big a deal to me.

Sure, I understood the need to let the Audience know when the story was going to end. And I loved the Limit's explanation as to why the structure of the movie Speed felt broken. But I continued to look away during discussions of the Limit, never emotionally connecting with the concept and how it worked into a story's argument. The Limit always seemed arbitrary, forced onto an otherwise elegant model, and sophisticated in its relationship between items.

Recent discussions in the Discuss Dramatica forums ignited my curiosity. Knowing the intricate details of Dramatica theory, and the seemingly out-of-place nature of the Story Limit[^noeffect], I set out to clarify the concept--only to figure out exactly why I couldn't connect with the Appreciation.

The definition did not describe the Dynamic's actual impact upon the meaning of a narrative.

So I coined a new Dynamic of story structure.

[^noeffect]: Altering the Story Limit appears to do nothing to the Storyform in the current version of the Dramatica Story Expert. It does—we just can't see it.

The Continuum

Time and Space are affectations of our consciousness; they do not exist in the Universe outside of our minds. This reality requires them to play a significant role in any model of human psychology. A model of narrative structure must account for the dynamic nature of these two aspects.

The relationship between time and space in the mind is simple—yet sophisticated in its role within a story's meaning:

A re-arrangement of spatial concerns defines a shift in temporal sequencing. A change in temporal sequencing re-arranges dramatic potentials.

In a practical example, the difference in flow (both temporal and spatial) is so subtle as to be almost unnoticeable.

Example:

You stand before a vast mansion estate with eight rooms. In one of those rooms sits hidden a small chest with the key to a billionaire's fortune.

You have 5 minutes to explore three rooms.

With the original Dramatica terminology, you would appreciate the Story Limit. Is this story a Timelock or an Optionlock? The answer defines whether the climax occurred from a dwindling duration or a disappearing set of options. Vast arguments abound on the forums arguing for both solutions: Is a sunset a Timelock or Optionlock?

It's neither.

The flow of space and time through the Continuum of the story told is all that matters. Are we seeing through linearity to see relativity? Or are we seeing through relativity to see linearity?

If I choose a downstairs bedroom, I see the temporal sequence. That room is first. As I choose an upstairs closet out of the remaining seven rooms (it's a big closet), I again see more of the temporal sequence. The closet was second; the downstairs bedroom was first.

The above is an example of a Spacetime Continuum. Re-arrange spatial concerns and you set a temporal sequence.

If I go back to the beginning and, instead of choosing a room, I spend no more than 2 minutes exploring one room (these rooms are enormous), I re-arrange the remaining rooms' potentials. This room came up empty; what awaits in the next? Will it increase the possibility of finding the key, engender more resistance, create more conflict, or make manifest the eventual outcome?

The above is an example of a Timespace Continuum. Set the sequence, and you see the balance of dramatic potential.

Answering the Call

The lazy man's illustration of the Story Limit before this understanding of Continuum was, "There are only so many blah blah blahs before the climax…" Meaningless to the Premise of a story and pointless to discussing what a story intends to communicate to an Audience. Who cares whether or not a story is about Ten Little Indians or 48 Hours? The answer to either leaves us manufacturing constraints out of what is ultimately an organic process.

With a better understanding of the relationship between time and space, we step closer to applying this Dynamic within our stories.

It's important to note that this new understanding is not a simple re-telling of the notion that an Optionlock feels like a Timelock to the characters, or that a Timelock feels like an Optionlock. Subjective ideas of Appreciations confuse and obfuscate practical application of Dramatica theory. Having consulted and helped develop novels, plays, musicals, video games, television series, and feature films, I know the most significant thing holding Authors back is the assumption that a Dramatica Appreciation is felt or understood by the characters.

It is not.

Dramatica is a theory for Authors—not for characters. It matters little to the meaning or stated intention on a story how a Dynamic " feels " to a character.

There is no universal "Answer to a Call" or an understanding of time running out or space, closing in as ultimately significant to a story's meaning. Any appreciation of pressure or confinement is a subjective perspective from within the story. Dramatica, and the Storyform to which time and space apply, is an objective point-of-view from without—the Author's view.

The Story Continuum is a relationship between space and time (all Dynamics are relationships) with subtle implications across the temporal sequencing of a narrative.

Which is why you can't see it in a current Dramatica storyform.

And why it exerts no perceivable influence on the "size" or scope of a narrative.

The Scope and Size of a Mind

In the past, Dramatica defined the Story Limit as defining the "scope" of a narrative.[^scope] As if setting Three Wishes or a Road Trip from NY to LA played some significant role in the message of a story. This definition is an over-generalization of the Dynamic's role in forming a narrative—a simplification in service of practicality.

To establish how much ground the argument will cover, authors limit the story by length or by size. Timelocks create an argument in which "anything goes" within the allotted time constraints. Optionlocks create an argument that will extend as long as necessary to provide that every specified issue is addressed.

What's easier to write? A story limited by length or size? Or a relationship between time and space across a continuum of consciousness?

Clearly, the former.

Dramatica was difficult enough to explain to Authors in the early 90s, so why not cut right to the chase to attract a broader Audience? The unfortunate side-effect of such a reduction is the assumption that this relationship between space and time somehow sets the size of the Storymind.

[^scope]: My article "Understanding the Continuum of a Narrative (formerly wrangling the "scope" of an entire narrative) played into this misunderstanding.

The Story Continuum is a Dynamic—a process of narrative. The Story Limit is static—seven sins, high noon, OptionLOCK, TimeLOCK—incongruent appreciations of what it means to be dynamic. A lock is a counter-intuitive concept within the context of the dynamics within a relationship. The very idea inspires one to set boundaries, limiting the scope of a story.

The same misplaced notion that assumes a "Limit" to wrangle the size and scope of a narrative leads one to see Actions and Decisions as Story Driver indicators. They're not. Actions engender decisions; Decisions manifest actions. It's the relationship between external and internal that concerns the Dynamic of the Story Driver.

The Story Limit is a misnomer. It categorizes a dynamic relationship as a static object, breaking any appreciable meaning from the relationship between space and time.

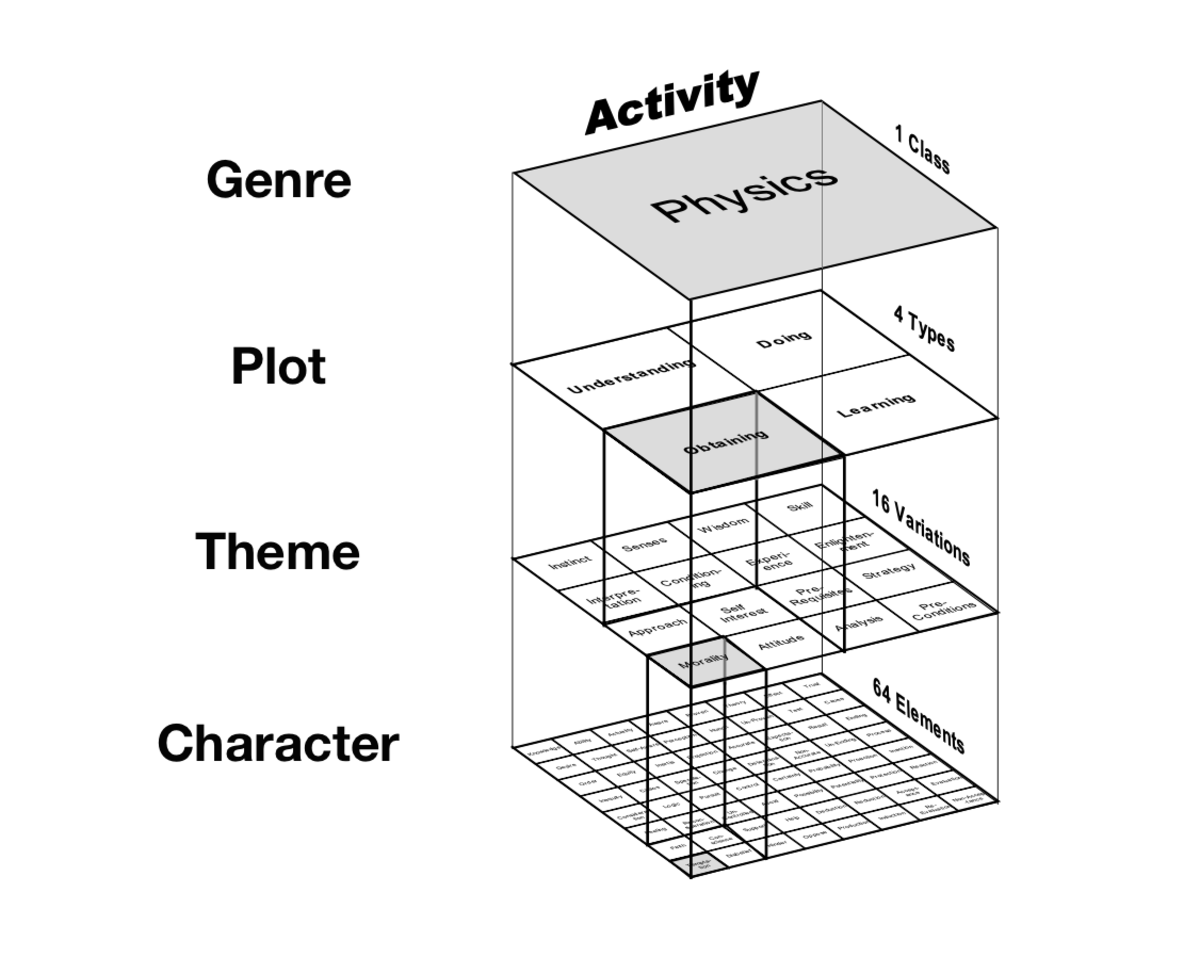

Further, it leads to a misunderstanding that the Story Limit somehow alters the Size of the Storymind. The Size of the Storymind is a fixed constant. The mind can only hold so many reference points before the holographic image of the narrative's meaning breaks down. This size finds representation in the four towers and four levels of the Dramatica model.

This model is a visual representation of the Size of Mind Constant. If you were to dive down below the Element level, you would lose sight of the top level. Anything beyond this, the mind loses, given the current story.

This situation is what happens when you write an Episode of a Television series, losing sight of the Storyform of the Series. You can approximate it with notions of Variations and Types, but you cannot see the Domains. Shifting the Size of the Mind constant to look below the Element level obfuscates the original top-level Domain. The result is an approximation, but no certainty, of the Series' ultimate meaning. Only once you experience the entire Series, can you look back and appreciate the show's purpose.

The box-car analogy provided by Dramatica co-creator Melanie Anne Phillips seeks to explain this Constant—you can only "see" or rest over four railroad ties at once. Move the box-car up or down and the scope of the Storymind shifts. This visualization is what is meant by the Size of Mind Constant: the box-car size does not shift, its location on the railroad track of consciousness does.

Practical Application of the Continuum

This new Appreciation of Story Continuum alleviates any struggle to identify the relationship between time and space in films like Ex Machina or The American President. In the former, engineer Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson) arrives for a fun and frivolous week with founding genius Nathan (Oscar Isaac). Timelock or Optionlock? Some would say both, some neither.

Spacetime or Timespace? Most definitely the second (notice I didn't say the latter 😊). Ex Machina is a narrative that exists in a Continuum of Timespace.

Each day ticked off re-arranges the potential for conflict in the next room (quite like the example above). The narrative of Ex Machina is an exploration in Timespace. Check this understanding against the alternate appreciation of the Continuum (Spacetime): what if there were no references to the days of the week, and only a focus on the change in potential as Caleb unravels Nathan's empire? Each stone unturned would be another in a sequence of events.

Spacetime applies a lens of relativity and sees linearity. Timespace sees relativity through linearity.

:: expert Advanced Story Theory For those more versed in the Dramatica theory of story, the Continuum describes the relationship between PRCO (Potential, Resistance, Current, and Outcome) and 1234 (a temporal sequence set). Does the PRCO of a dramatic unit define 1234 or does 1234 alter the PRCO of a specific unit?

This is a relativistic relationship. Both happen simultaneously.

The answer determines where and when space and time fall out of phase with each other. ::

Avoiding Cause and Effect

This Continuum sets the flow of narrative concerns through the model vertically, a temporal aspect to reflect the spatial relationships across the horizontal plane. Whether employing Spacetime or Timespace to appreciate the relationships within a narrative, this Continuum flows up and down through the model resulting in Acts, Sequences, Scenes, and Events. By means of comparison, the horizontal relationships work across Genre, Plot, Theme, and Character.

The Dramatica theory of story coined the term frictals to describe these times spiraling vertically through the model. This relationship is NOT a cause and effect similar to the Story Driver. Space does not lead to Time, nor does Time lead to Space.

The Continuum of consciousness within the Storymind is a relationship of relativity—a fundamental dynamic of self-awareness.

The Storyform is a holographic image of a story from beginning to end. While the Audience experiences the story one piece at a time and therefore interprets various Storypoints from within, the Author writes from without knowing the relationship between space and time.

He or she knows which comes first in the sequence, and the re-arrangement of potentials. It isn't something discovered after the fact or written in sequence, but an appreciation of flow inherent in every story, vibrating out-of-sight and below the surface.

Removing the Limits on Storytelling

The distinction between a concept of Story Continuum and the original appreciation of Story Limit is slight, yet massive in practice and focus of attention. The latter is fixed, restrictive, and potentially misleading in its play upon the forces of a narrative. The former is conceptual, a factor of process over static observation, but one infinitely more applicable to the mind of a story.

How do you write Spacetime or Timespace?

Intention.

The Dynamic of your intended direction is the path.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.