Tying the Towers of Story Structure Together

Storytelling's timeless backbone: exploring the integrity of structure through Dramatica theory

Ever wonder why the works of Shakespeare endure hundreds of years later? What of Tolstoy or Shaw? One possible explanation exists, an explanation that has everything to do with the integrity that comes with a solid story structure.

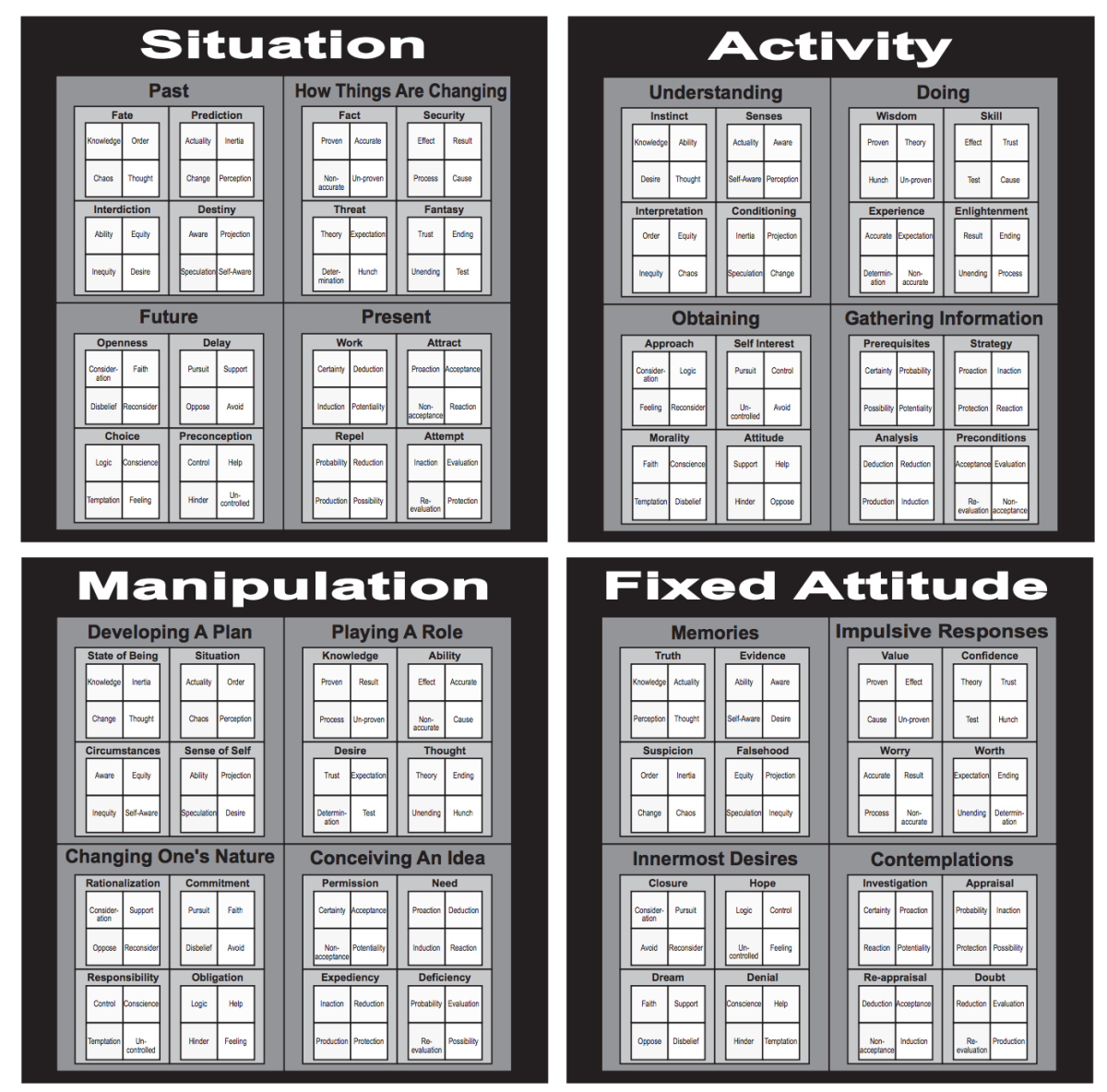

What discussion of story structure could be considered complete without a chart? Those attracted to such devices--structuralists-- love order and pounce on every opportunity to see storytelling delineated into clearly defined boxes. Luckily, the Dramatica theory of story structure (narrative science) has the ultimate chart for these crazed lunatics:

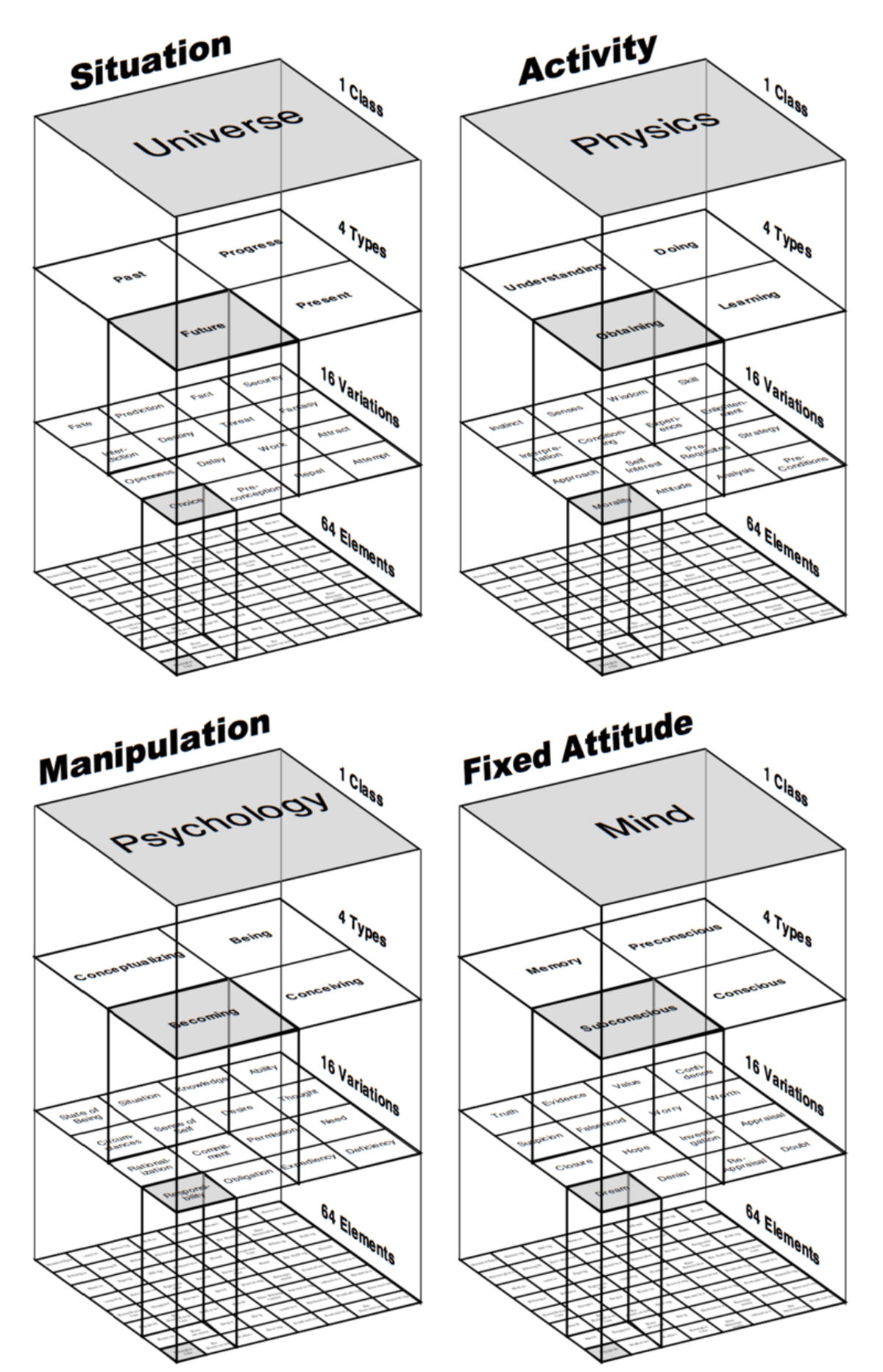

Impressive yes? This Table of Story Elements breaks the individual pieces of narrative down into separate and distinct families of elements. At first glance it seems to be simply a collection of familiar and not-so-familiar terms, but look what happens when one pulls back and shifts the point-of-view ever so-slightly:

From this angle one can see that the Dramatica Table of Story Elements exists as a 3-D model of story-structure! More than simply a linear progression of timed events, this model of story frames a complete model of human psychology by breaking down narrative into four distinct levels--Character, Plot, Theme and Genre. This chart does more than define a story...it is story.

But stories are monumental things and to build something as full and robust as a great classical narrative one has to reach ever higher and higher. Only one catch. Anyone who has ever sat down with a bucket of Legos and a 6-year old eventually reaches that point where they can't build the tower any higher without risking collapse. Multiply this by four and the need for a solid foundation and perhaps even some interlocking "bridges" becomes all too clear.

So what is that keeps these towers of psychological structure from toppling over?

Character

Looking at the very bottom level of the structure one finds the various elements of character found in every great story. Temptation, Chaos, Proaction and Expectation represent just a small portion of the 64 individual "traits" that can be combined and mixed to create character.

Examining further one may also notice that the same set of 64 elements repeats itself within each tower--albeit with slightly different arrangements. This falls in line with the theory as each "tower" really acts like a lens focused on the same thing--namely, the story's central problem. The throughlines represented by each tower offer audiences perspective (I, You, We and They) and this point-of-view--depending on where one is looking from--determines how those base elements will appear.

But more importantly, these similar elements offer the first and strongest instance of the ties that bond the throughlines together.

Depending on the story's dynamics 2-3 of these towers will share the same Problem and Solution element. In other words, they'll see the story's central problem as being the same thing. Likewise 2-3 of them will see the Focus and Direction to those problems as being the same. Regardless of the story's dynamics, in the end, all four throughlines will interconnect by virtue of these common elements. Thus, the similarities in how these perspectives witness the conflict and apparent conflict pull the four throughlines together, binding them together tightly at the base.

Theme

The next level up one finds a another set of entanglements, only this time more thematic in nature. Set apart into 64 touch points across all four throughlines (as opposed to the 64 found in each at the Character level), these Variations define the various Issues and Counterpoints found in each Throughline.

But they also call to attention the Unique Abilities and Critical Flaws of the two central characters--the Main and Obstacle Character--and the Catalysts and Inhibitors of the Overall and Relationship Throughline.

Interestingly enough, again depending on the story's dynamics, several of these appreciations will be found in a tower other than the one they are associated with. A Main Character dealing with issues of Preconception (in the Universe tower) might find their critical flaw in his or her Approach (located in the Activity tower). Likewise a Relationship with deep Commitment issues (the Psychology tower) might find doing what is best for others (Altruism, again in the Activity tower) a real downer to their relationship. Regardless of the particulars, these connections and similar thematic tissue insure that these towers of structure won't topple into one another.

From here on up the connections become looser and less entangled. This makes sense--one would hope the foundation to be rock solid, while simultaneously allowing for a little wobble towards the top.

Plot

The next step higher one finds 16 cornerstones of structure most akin to plot. Past, Progress, Doing, Obtaining--all different elements of plot that define the type of narrative conflict found in each and every Act.

They also help guide the audiences attention in the right direction. In order for a story to "hold together", the major Concern--or area of focus--for each Throughline must be centered in the same quadrant for each story. In other words, if one Throughline finds itself concerned with Obtaining, then the other Throughlines must have Concerns of The Future, Subconscious and Changing One’s Nature. If instead the Concern is Doing, then Progress, Impulsive Directions and Being must show up as Concerns in the other throughlines. In this way, a story guarantees that the viewer (or reader) will be able to appreciate some meaning by looking at the same thing through different eyes.

Note that the connections here do not involve cross-pollination as they did with the previous two levels. They begin to show the signs of individuality one would find in broadening the scope of the viewport. Similarities appear because of the consistent focal point, but they don't involve thematic or elemental material from another tower.

Genre

Upon reaching the zenith of each story structure tower, one finds the four basic ways of categorizing (or seeing) conflict. No matter what the source of trouble for characters in a story, conflict must always fall in either a Universe, an Activity, a Psychology (or Psychology) or a Mind. It's impossible to define conflict any other way.

But you'll notice how broad and general these terms are when compared to the specifics found in the lower levels. By assigning the throughlines to these four domains of conflict, one sets the personality of a story: and thus why they come closest to defining Genre.

But Genres are fluid, like personalities, and thus the ties that bond them are looser in nature than those below. Make no mistake they still exist: external conflicts across the top (Universe and Activity), internal along the bottom (Mind and Psychology), states, or static sources of conflict across one diagonal (Universe and Mind), and processes of conflict spanning the other (Activity and Psychology). Here the towers connect through their relationships to one another, thus creating a holistic model out of something that on the surface appears strictly logical. While not as tangled and intertwined as the base, this highest level of story structure works to maintain the integrity of the mechanism as a whole.

Solid Construction

Understanding the connective tissue between these towers helps one to better appreciate the complexity of a solid and complete story. Those tales and flights-of-fantasy fiction that ignore the common-sense building techniques of solid structure risk creating a faulty and ultimately doomed enterprise. With the knowledge of the psychological underpinnings related to the construction of a working story, authors everywhere can build structures destined to survive several lifetimes.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.