Writing a Screenplay with Dramatica

Misconceptions and limitations in popular storytelling paradigms

Misguided conclusions abound regarding the Dramatica theory of story with many claiming that this revolutionary look at structure is only good for after-the-fact analysis, not writing. Such thinking flows from a lightweight understanding of what the theory is, and isn’t.

When it comes to popular models of screenplay structure, whether it be Robert McKee, Michael Hague, John Truby or Blake Snyder, many writers flinch at the prospect of following a simplistic formula. How can the complexity of Hamlet or the subtlety of character growth in To Kill a Mockingbird be possibly broken down into a simple set of common sequences? This instinct to rebel seems appropriate given the reductive nature of many of these paradigms.

The problem isn’t that these ways of looking at structure are particularly wrong. In fact, for many stories, they can be quite revelatory in their explanations of proper sequencing and emotional growth of character. Where they fall short, however, is in the breadth of their understanding. Accuracy becomes a casualty of these efforts to pare down the complexity of a complete story into a bite-sized catch-word paradigm.

An all-encompassing understanding of story

Dramatica sacrifices easy digestion for high accuracy. The theory is not easy to understand because story is a complex and complicated beast. When people in development say “trust the process,” what they are really asking for is more time — more time for their inaccurate or simplistic models of story to eventually arrive at a story that sort of works. This hopeful anticipation drives those long periods of development time when really it should be purposeful intent at the helm. Dramatica, while significantly front-loaded on the initial comprehension level, ultimately saves time by delivering a precise and meaningful understanding of the story an Author wishes to tell.

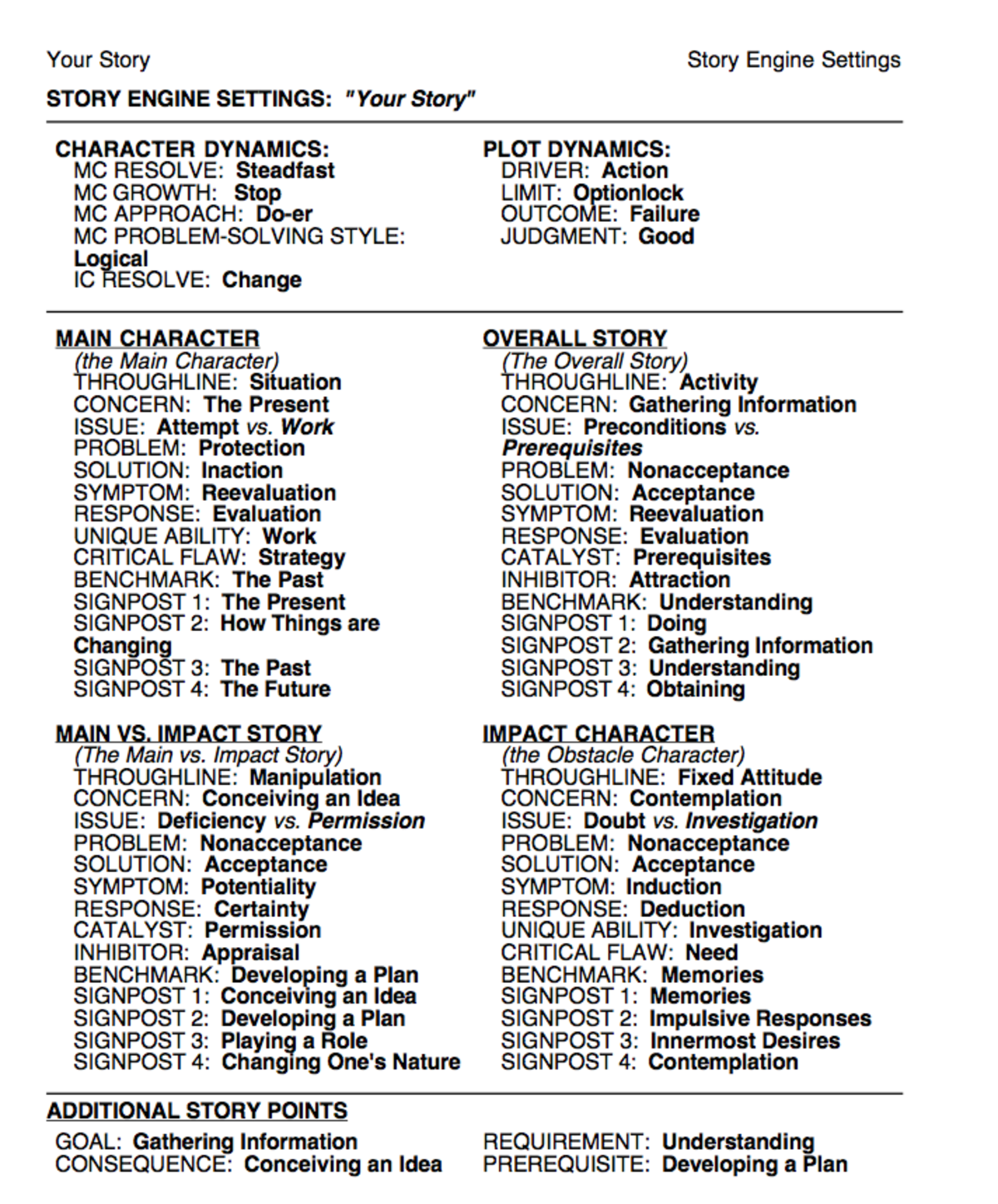

The key is the storyform

Once a writer determines what it is they want to say with their film, the Dramatica theory of story presents them with what is known as a storyform. This collection of sixty or so elements of structure elaborates in great detail the meaning or message the Author wishes to communicate. Balancing purpose with the sequence required to deliver it effectively, the storyform represents a holistic snapshot of the human mind trying to resolve a particular problem. And because complete stories are about solving problems, there can be no better tool to construct an effective work of narrative fiction than this simple one-page report.

Meaning exists independently of subject matter

While the storyform is precise in its arrangement of thematic elements, how they are exposed to an audience is left completely up to the creativity and talent of the individual Author. Take for instance the storyform for Dreamworks’ How To Train Your Dragon. At first glance it might look less like an emotionally compelling movie and more like a collection of semi-scientific words that seemingly have nothing to do with telling a story. But upon closer examination, certain items might resonate with one familiar with the message of the film. Stoick’s Problem of Rejection and his eventual Solution of Acceptance, as covered in the article What It Means to Fail, can be found under the Obstacle Character’s Throughline. Likewise the bittersweet Personal Triumph of Success/Bad, as detailed in the article When Failure Becomes a Good Thing, sits up top under Plot Dynamics. In fact, the more comfortable one becomes with the terms listed in this report, the more obvious it is that this storyform is a very accurate representation of the meaning behind How to Train Your Dragon.

But it does not just have to be an animated film about Vikings and dragons. In fact, this storyform is the foundation for any story that wishes to explore the same thematics and come to the same conclusions regarding acceptance and learning.

Writing from intent

Let’s say we wanted to write a modern sci-fi thriller, something along the lines of Moon or Sunshine. We know that the exploration of other planets and other worlds is the next step for human advancement and that one of the most interesting places to start would be the icy moon of Jupiter, Europa. Why? There are some in the scientific community that believe its thick icy crust protects an ocean of life unlike anything we have here on Earth. What if, in the middle of this century, there was a manned mission to uncover the truth beneath the surface and what if this mission went horribly wrong?

Following the current trend of single-word titles, we’ll call it Europa. The film would be a taught character-driven piece about isolation and our influence on the universe around us and attempt to have the same emotional impact that Dragon had. It will follow an expeditionary force of astronauts, scientists and most importantly students eager to learn the right, and wrong way of collecting scientific evidence. Taking the above storyform as a basis for the dramatic intent of our piece, we can begin to outline or imagine how the film will play out.

Exploring the storyform

Before writing word one, we already know how the film is going to end — the world is not going to learn what is under that icy surface (Story Outcome of Failure). We also know that our Main Character (Aaron?), as Antagonist, will be satisfied as to this outcome because he would have been the problem student working to prevent it all along (as Hiccup was in Dragon — for further explanation, please see the article How to Train Your Inciting Incident). How exactly this will all play out is, of course, up to us, but we know going into it that the efforts to reach the Story Goal are going to end in Failure just as they did in Dragon.

Beginnings

We also know the Act order the characters will go through - Doing to Learning to Understanding to Obtaining. This means that in the First Act the scientists/astro-students will be landing on the surface of Europa, perhaps arguing over the best place to land, trying to balance their safety with the safety of the inhabitants below. This argument would showcase their conflict with Doing. Maybe, in an effort to Protect the sanctity of life below (Aaron, after all, is driven by Protection), our Main Character covertly hacks the ship’s computer so that they are unable to land safely. This Action could be the Plot Point, or Story Driver, that pushes our story into the structural second act.

The Second Act

So then we have the monster of the Second Act to focus our attention on. No need to panic though because we know, in order for our story to be meaningful, that it will begin with our characters focusing on Learning and then somewhere past the middle, begin to focus on Understanding. Perhaps the Protagonist Head Scientist/Teacher (Marcus?), driven to succeed at all costs (his theoretical concepts are at stake here), mounts a daring excursion to the surface using the ship’s unreliable escape pods (They’ve come all this way, after all…). They leave one crew member on-board to watch over things, then head down.

Once they’re on the surface, we can begin to play out the conflict between Marcus as he tries to gather evidence of the mystery below the icy crust, and Aaron’s drive to get them to reconsider the dangers of impacting life below. Marcus can’t understand why Aaron would get so worked up about some fish, Aaron thinks all life is precious and autonomous. We could have all the classic back-and-forth arguments, with perhaps the group splitting into two factions. This would all come to change though with the shift into the second-half of the Second Act when they would stumble across some great deep revelation about life beneath the surface. Something along the lines of discovering that really big dragon in How to Train Your Dragon.

What if they realize that there aren’t just single-cell fish underneath, but an entire ecosystem of alien life living in harmony beneath the surface? Marcus, and his drive to prove his theories appropriate, upsets the quiet world of the aliens and drives them to attack the expeditionary crew. Marcus would see this as the attack of monsters that must be destroyed. Aaron would see it as life simply trying to defend itself from outside influence. This new conflict over Understanding would come to be the focus of the rest of this Act.

They would race back to their escape pods, trying desperately to communicate with their ship above. Students and scientists would lose their lives, yet Aaron would still be working to protect this misunderstood alien-life form. Eventually it would have to come to an end with an Action as equally powerful as Hiccup’s refusal to kill the fiery Monstrous Nightmare. Perhaps once they arrive back at the ship, maybe even with some alien specimens on board, Aaron destroys all radio communications. What better way to protect these guys than to make sure no one ever finds out about them?

Climax and Resolution

This Action would drive our story into its Fourth and Final Act, that of Obtaining. And here, the outcome of Failure falls perfectly into place. Aaron is going to win. He is going to prevent the world from learning about Europa, but how exactly? By destroying the ship and every crew member on-board. In this climactic battle, both Marcus and Aaron will face off, with Marcus wanting to arrive back safely on Earth. Perhaps even the remaining crew members would rebel and misbehave just as the young Vikings did in Dragon, maintaining the inequity created by Rejection. Aaron eventually succeeds, maybe by driving the ship into the heart of Jupiter itself, crushing him, and everyone on-board leaving no trace of their ever having existed.

This failure will mean that the Consequence will occur - something to do with Conceiving. Either the world will have to come up with some explanation as to why the crew never returned home or why they never even bothered to radio a message. It could be painted in a positive light as it was in Dragon, Europa could return to the peaceful quiet world it once was while Earth continues to revolve in constant turmoil. Beyond simply bringing the story to a close, this kind of ending guarantees that there was a reason for the story to play out the way it did and for existing in the first place.

Audiences love it when their time isn’t wasted.

Personal Issues

But remember too that the storyform calls for the Main Character to have resolved their personal issues. As Aaron drives the ship into the eye of Jupiter, there will be a smile on his face. He will have overcome his own personal issues. In Dragon it was Hiccup’s diminutive physicality, in Europa? Perhaps it could be Aaron’s reputation as the under-achiever of the group. Maybe the crew was a tight-knit group of scientists who went to the same school or worked at the same place, and Aaron was always seen as an outsider. His scores on the aptitude test would have been drastically low compared to the others, and his scientific career a joke. The others would always see him as lazy or incompetent because he couldn’t keep up with them. Well, saving an entire world from destruction and scientific experimentation could be seen as quite an accomplishment, couldn’t it? This would give his decision to destroy the ship meaning and details again the power of the Dramatica storyform. While bringing about the failure of the mission, the Main Character would be overcoming their own personal angst of not living up to the others. He would have accomplished something no one else could have and all by remaining Steadfast to his core beliefs.

Filling in the Pieces

Already we have a pretty strong story, something more meaningful than what one usually finds in theaters today. But there is still so much more to work on. We have yet to identify the Obstacle Character. It could be Marcus, like it is Stoick in Dragons. But maybe we want to explore something even more deeper. After all, this could be a film that runs 110-120 minutes, not simply an animated film of 90. Maybe there would be another crew-member, one of the other scientists, a skeptical tough-as-nails astronaut who hates bookworm types or maybe even the ship’s computer that would share that same perspective of not accepting Aaron for who he is. A relationship would develop between Aaron and this entity, a relationship that would eventually heal itself with the acceptance coming from the other party’s significant change of character.

The point of all this is: we have the framework for a meaningful story that we can begin to write from. Whether or not the final work is a success is, as always, entirely up to us as writers. Is Europa a guaranteed blockbuster success? No. Does the story actually mean something? Does it have some purposeful intent behind the machinations of character, plot, theme and genre? Without a doubt. The Dramatica software, and the theory it is based on, does not write the story, does not flesh out the characters, or bring life to their dialogue. It simply provides the pieces needed and the order in which to lay them out in order to arrive at the meaning one wishes to achieve.

The rest is all luck.

A Million Different Stories

Now we could apply this storyform to any kind of genre: War Drama, Western, Romantic Comedy, it doesn’t matter. All that goodness of color and human expression is left up to us. And this isn’t the only storyform possible. The current incarnation of Dramatica offers writers over 32,000 different unique stories. With each storyform carrying the possibility of millions of different interpretations (as exemplified above), the possibilities for creative expression become endless. It should also be noted that the current model is only one portion of the entirety of the theory. There are actually countless more storyforms possible — they would only require a different model and a different set of givens hardwired into the system. For now though, the model in place is excellent for providing Authors with the clues needed to write something meaningful and lasting well beyond their years.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.