Writing Characters Who Break the Mold

Moving away from the familiar and into the unexpected.

In the previous two articles in this series on Creating Complex Characters in Complex Times, characters were seen not as real people, but rather as analogies to the forces at work in a single mind. Eschewing notions of good and evil, this objective appreciation of story as psychology allows Authors to see the Players in their story for the very first time.

When seen objectively, Archetypal Characters represent forces within the mind. The Protagonist showcases our drive towards initiative. The Antagonist, our tendency towards reticence. The Guardian acts as the voice of Conscience, and the Contagonist a source of Temptation.

These Archetypal Characters consist of a perfect arrangement of Narrative Elements. Like-minded drives such as Pursuit and Consider make up the Protagonist, Avoid and Reconsider the Antagonist. The Guardian finds Conscience and Help at his core, while the Contagonist seeks to Hinder and introduce Temptation into the story.

Greater complexity and heightened interest are found by mixing and matching these Elements—by moving against expectation and playing unlike-minded Elements against each other within the same Player.

Aliens and the Story Goal

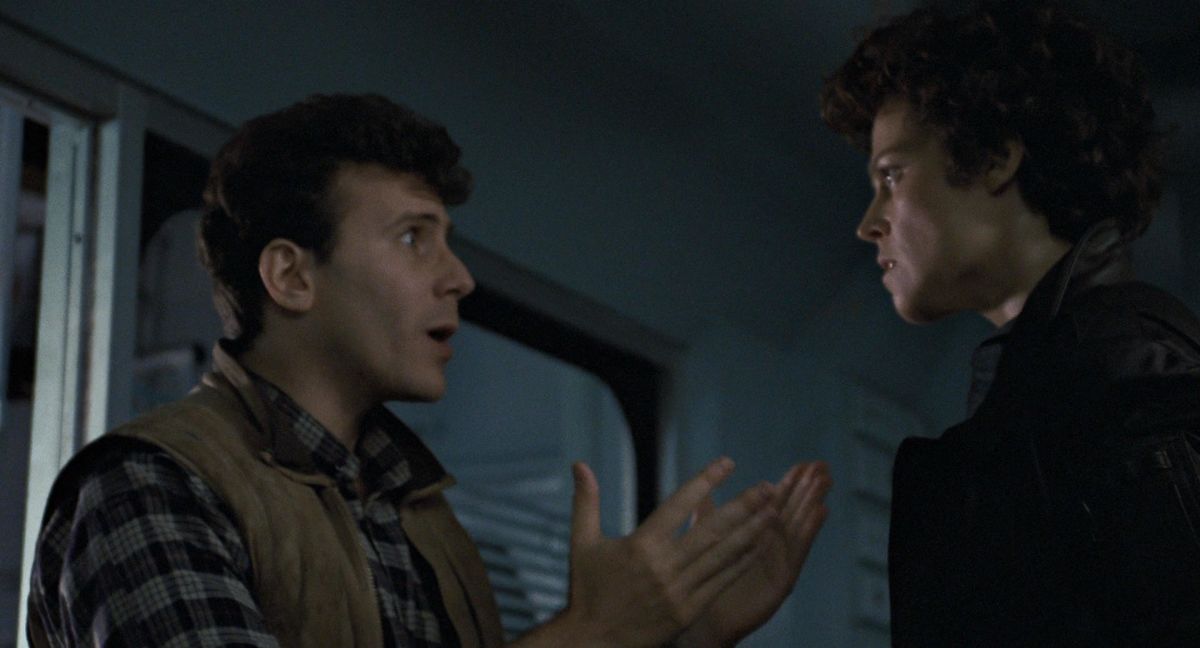

James Cameron’s Aliens provides an excellent example of this sophistication of characterization in action. While the Protagonist and Antagonist remain Archetypal (Ripley and The Aliens respectively), the Guardian and Contagonist err on the side of greater complexity.

It may seem, at first, that the Story Goal of Aliens is to kill the Aliens. After all, Ripley says as much when Carter (Paul Reiser) offers her the job.

While she does want to eradicate every last one of them, Ripley only wants to do so because she understands the danger they represent for the human race. Her motivations of Pursuit and Consider are always focused on getting out, and making everyone appreciate the severity of the situation.

The Story Goal of this film, then, is to understand what happened to the colonists of LV-426. This involves learning what happened to them and bringing that information back home.

Killing the Aliens is not the Story Goal. While their destruction is a crucial step, achieving it fails to resolve the fundamental inequity set forth at the beginning of the story. The colonists mysteriously disappear, and efforts begin to understand why they vanished.

Ripley pursues a course of action towards this understanding. The Aliens work to prevent it.

Working Against Conscience

Carter (Paul Reiser) is a stooge for the Weyland Corporation. Motivated to bring back alien DNA at all costs he sets the team up—knocking over alien test tubes and hoping to embed some embryos in a host subject for the ride home.

Is Cater the Contagonist, or the Guardian?

Subjectively, Carter is a prick—we all universally hate him. But objectively, his shenanigans actually assist the efforts to understand what happened to the colonists. His attempt to impregnate Ripley helps her efforts towards a greater understanding of these Aliens—from an objective point-of-view.

Bishop (Lance Henriksen) is an android. His creepy demeanor reminds Ripley of the consequences of working with a programmed entity. His failure to show up at the appointed time during the climax only exacerbates her distrust.

Is Bishop the Guardian, or the Contagonist?

Subjectively, Bishop is plain weird. Objectively, he displays temperament throughout the chaos—acting as a virtual voice of conscience. Yet, his failure to show up on time hinders Ripley’s ultimate mission.

The Archetypal Element Swap

Carter is neither Guardian nor Contagonist—yet consists of Elements of both. Bishop balances Carter out by taking on the converse Elements.

Carter represents Help and Temptation in the Storymind of Aliens. Disregarding the potential consequences of bringing home alien embryos, Carter assists the efforts to understand what happened to the colonists.

Bishop represents Hinder and Conscience in the Storymind. A constant reminder of what happens when you’re not prepared, Bishop delays and distracts from a greater appreciation of the missing colonists.

The Complex Character

Compare the relative interest level, from the Audiences perspective, of Ripley and the Aliens to Carter and Bishop. We know what Ripley is all about, and we can say the same for the Aliens. No surprise there. It’s clear who is for, and who is against.

When it comes to Bishop and Carter, the dividing line between for and against blurs. The interest level—and surprise factor—increases because we don’t instinctively know what motivates these characters.

In the Dramatica theory of story this process of exchanging Narrative Elements is known as an Archetypal Character Swap. When the natural set of Elements begins to drift apart, that Player’s function within the story becomes less archetypal and more complex. That greater complexity is what drives greater interest within the minds of the Audience.

Breaking the mold is merely an act of breaking the Archetype.

title: Writing Characters Who Break the Mold tldr: Moving away from the familiar and into the unexpected. banner_slug: 2019-02-04-113047 concepts:

- story goal

- Objective Story Character Elements series: 'creating-complex-characters-in-complex-times' post_type: article published: '2019-02-04 11:28:00' id: fdd22bc0-3f93-4e7e-85bf-daca9cdd2c8d

In the previous two articles in this series on Creating Complex Characters in Complex Times, characters were seen not as real people, but rather as analogies to the forces at work in a single mind. Eschewing notions of good and evil, this objective appreciation of story as psychology allows Authors to see the Players in their story for the very first time.

When seen objectively, Archetypal Characters represent forces within the mind. The Protagonist showcases our drive towards initiative. The Antagonist, our tendency towards reticence. The Guardian acts as the voice of Conscience, and the Contagonist a source of Temptation.

These Archetypal Characters consist of a perfect arrangement of Narrative Elements. Like-minded drives such as Pursuit and Consider make up the Protagonist, Avoid and Reconsider the Antagonist. The Guardian finds Conscience and Help at his core, while the Contagonist seeks to Hinder and introduce Temptation into the story.

Greater complexity and heightened interest are found by mixing and matching these Elements—by moving against expectation and playing unlike-minded Elements against each other within the same Player.

Aliens and the Story Goal

James Cameron’s Aliens provides an excellent example of this sophistication of characterization in action. While the Protagonist and Antagonist remain Archetypal (Ripley and The Aliens respectively), the Guardian and Contagonist err on the side of greater complexity.

It may seem, at first, that the Story Goal of Aliens is to kill the Aliens. After all, Ripley says as much when Carter (Paul Reiser) offers her the job.

While she does want to eradicate every last one of them, Ripley only wants to do so because she understands the danger they represent for the human race. Her motivations of Pursuit and Consider are always focused on getting out, and making everyone appreciate the severity of the situation.

The Story Goal of this film, then, is to understand what happened to the colonists of LV-426. This involves learning what happened to them and bringing that information back home.

Killing the Aliens is not the Story Goal. While their destruction is a crucial step, achieving it fails to resolve the fundamental inequity set forth at the beginning of the story. The colonists mysteriously disappear, and efforts begin to understand why they vanished.

Ripley pursues a course of action towards this understanding. The Aliens work to prevent it.

Working Against Conscience

Carter (Paul Reiser) is a stooge for the Weyland Corporation. Motivated to bring back alien DNA at all costs he sets the team up—knocking over alien test tubes and hoping to embed some embryos in a host subject for the ride home.

Is Cater the Contagonist, or the Guardian?

Subjectively, Carter is a prick—we all universally hate him. But objectively, his shenanigans actually assist the efforts to understand what happened to the colonists. His attempt to impregnate Ripley helps her efforts towards a greater understanding of these Aliens—from an objective point-of-view.

Bishop (Lance Henriksen) is an android. His creepy demeanor reminds Ripley of the consequences of working with a programmed entity. His failure to show up at the appointed time during the climax only exacerbates her distrust.

Is Bishop the Guardian, or the Contagonist?

Subjectively, Bishop is plain weird. Objectively, he displays temperament throughout the chaos—acting as a virtual voice of conscience. Yet, his failure to show up on time hinders Ripley’s ultimate mission.

The Archetypal Element Swap

Carter is neither Guardian nor Contagonist—yet consists of Elements of both. Bishop balances Carter out by taking on the converse Elements.

Carter represents Help and Temptation in the Storymind of Aliens. Disregarding the potential consequences of bringing home alien embryos, Carter assists the efforts to understand what happened to the colonists.

Bishop represents Hinder and Conscience in the Storymind. A constant reminder of what happens when you’re not prepared, Bishop delays and distracts from a greater appreciation of the missing colonists.

The Complex Character

Compare the relative interest level, from the Audiences perspective, of Ripley and the Aliens to Carter and Bishop. We know what Ripley is all about, and we can say the same for the Aliens. No surprise there. It’s clear who is for, and who is against.

When it comes to Bishop and Carter, the dividing line between for and against blurs. The interest level—and surprise factor—increases because we don’t instinctively know what motivates these characters.

In the Dramatica theory of story this process of exchanging Narrative Elements is known as an Archetypal Character Swap. When the natural set of Elements begins to drift apart, that Player’s function within the story becomes less archetypal and more complex. That greater complexity is what drives greater interest within the minds of the Audience.

Breaking the mold is merely an act of breaking the Archetype.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.