Writing the Story That Is You

Getting to know your creative impulse

"Know thyself" is a phrase well-understood by Authors. The process of writing a story often turns out to be more of a revelation of self, rather than an exploration of imaginative worlds and characters. The greatest struggle, then, is not of plot and theme—but rather, of exposure to introspection.

Dramatica and its recognition of storyform require Authors to step out of their comfort zone. Understanding the intricacies of one's creative impulse leads to an abandoning of the process—a measure meant to protect one's internal drive.

There's only some much cognitive dissonance one can process before the model itself stops being useful for the thing that actually matters to me, which is writing the best books I can. And this brings us to the problem of Dramatica's notion of Premise and a novelist's writing process.

Dramatica is a model of the mind engaged with inequity resolution. The path through this model is not a simple process, and assumptions about it can lead one to jump to incorrect conclusions about the theory. This series of articles on The Hegelian Dialectic hopes to make sense of the dissonance felt by many learning this theory for the first time (or the hundredth).

Let's agree right off that there are as many ways of writing a book as there are writers, so what doesn't work for me might work brilliantly for others.

I agree.

We touched on this in some earlier e-mails, but Dramatica's notion of Premise is one in which the writer has to know exactly what they want to say, formulate it in a highly didactic and (for the less than expert in Dramatica's terminology) semantically obtuse fashion.

Yes. The only way you can effectively structure your story is if you know what you want to say. You can't structure an idea. Meaning is organized Truth, and unless you know that Truth—you can't structure your story into something meaningful.

As far as terminology goes, they are "semantically obtuse" because they describe concepts of inequity in motion—not real things unto themselves. They require one to step back and appreciate the meaning of the word. It's the only way a model of the mind can work.

Knowledge in Dramatica is not just what you know, but rather knowing. The Past is not merely what happened, but past-ing—always concerning oneself with what happened. Both appear as imbalances, or inequities, within the story.

Obtuse, perhaps. But ultimately necessary when modeling the subtle complexities of the mind's problem-solving process.

Starting with a Question

Questions do not require structure; practical answers to them do. The "didactic" nature of a Premise is necessary to understand when it comes to choosing the right arrangement for a particular solution. Without it, an Author can never be sure exactly what it is he wants to communicate.

But I'm a novelist, not a polemicist.

Is the purpose of To Kill a Mockingbird not to argue the failing of prejudiced thought? Is Hamlet not about the tragedy of overthinking one's sense of self?

Is Romeo and Juliet just a good love story?

The purpose behind great stories is their Premise. Unlike polemicists who attack through debate, the storyform makes the appropriate response to conflict apparent through reason and emotion.

No debate—only recognition.

The storyform is not an active dialogue; it's an answer to the Authors purpose in writing his or her story. Dramatica says stories are more than merely a place to entertain an idea—they're opportunities to make those ideas meaningful.

I start with a thematic question I want to explore: "if all your ideals fail you, should you hold onto them or adapt to the pragmatism of the world around you?" or, in the case of Skyfall "the world has changed so much that it no longer seems to need old-school spies anymore. It's computer hacking and drone missiles now, not fisticuffs and cunning, So should they all retire, or is there still something important about the old ways of doing things?" Those are questions that can make one get out of bed to write the next chapter.

Some writers look at a blank page and see a blank canvas full of infinite possibilities. Others see a wall, impenetrable and overwhelming. Motivation by question works great for the former group. Motivation by Premise aids the latter.

As you mentioned, what works for one Author might not work for another.

Regardless, there will come a time when both have to reckon with the meaning of their story. The wall-people get that work done first.

"Stop being deviation and you can obtain" or even the slightly friendlier, "When you get out of your way and give up being inadequate for a particular group you can fight global terrorism", don't give me much of an impulse to write. That doesn't mean Dramatica is intellectually wrong, but it does stop it being useful for me as a novelist.

Imagine you just finished your first draft. A couple of people read it and offer their notes. Your editor takes a look at it. She says a lot of the same things. Even you take the time to go through it and markdown recommendations to make it better.

Wouldn't it be nice if you could make sense of all that feedback? Wouldn't you like to know why the same problems pop up? How about knowing the content of the argument you ended up making to your Audience?

Sure, you can address problems of entertainment and humor and characterization on your own. But what about what it all means? If you couldn't figure that out from the outset, who's to say you managed to bring it all together in the end?

It would be nice to have an objective friend there, reflecting your artistic impulses.

Dramatica and Subtxt are those friends.

Cafeteria-style Story Theory

Dramatica is a sophisticated and comprehensive understanding of narrative theory. As it deals with the intangible processes of the mind, applying all the concepts can be challenging even for the most talented writers. Cherry-picking the essential parts at least sets you off in the right direction.

So here's what I still find useful about the Dramatica model:

One: The four throughlines. Making sure I've got an Objective Story, a main character story, and influence character story, and a relationship story that all tie together makes the stories not just clearer but better.

Setting up the Four Throughlines is the absolute most crucial step. If you do this, you will be better off than 90% of the stories out there.

Two: The idea of conflict taking place predominantly within four domains of activities, situations, fixed attitudes, and manipulation (or their older names) also brings opportunity for clarity and focus, even if I've never quite been able to successfully "slot" my throughlines into those domains conveniently.

This balance of conflict exists at all levels of your story. Acts, Sequences, Scenes. Each offers an opportunity to examine the different areas of inequity we encounter in our daily lives.

Our minds see conflict in terms of situations, activities, fixed attitudes, and manipulations. That's why it's so important that a story deal with all four. Leave one out, and the Audience starts to feel you're not telling them the whole story.

- Recognizing that in each of those domains, I'll need to explore the four concerns at the level below gives both inspiration and a sense of finding completeness.

That sense of completeness is part of the model.

We look at a narrative Element, and our minds instinctively break it down into four children Elements. These sub-Elements represent the situation, activity, fixed attitude, and manipulation of the parent Element above.

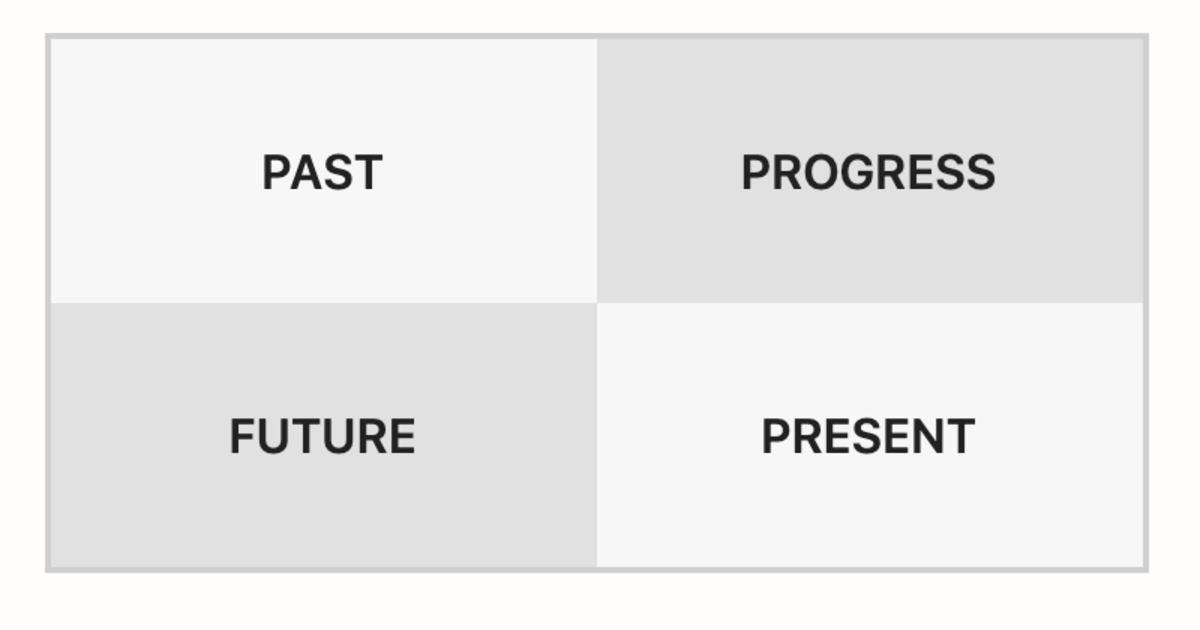

- The Past is the situation of the Universe

- Progress is the activity of the Universe

- The Present is the fixed attitude of the Universe

- The Future is the manipulation of the Universe

And this fractal relationship continues down the model.

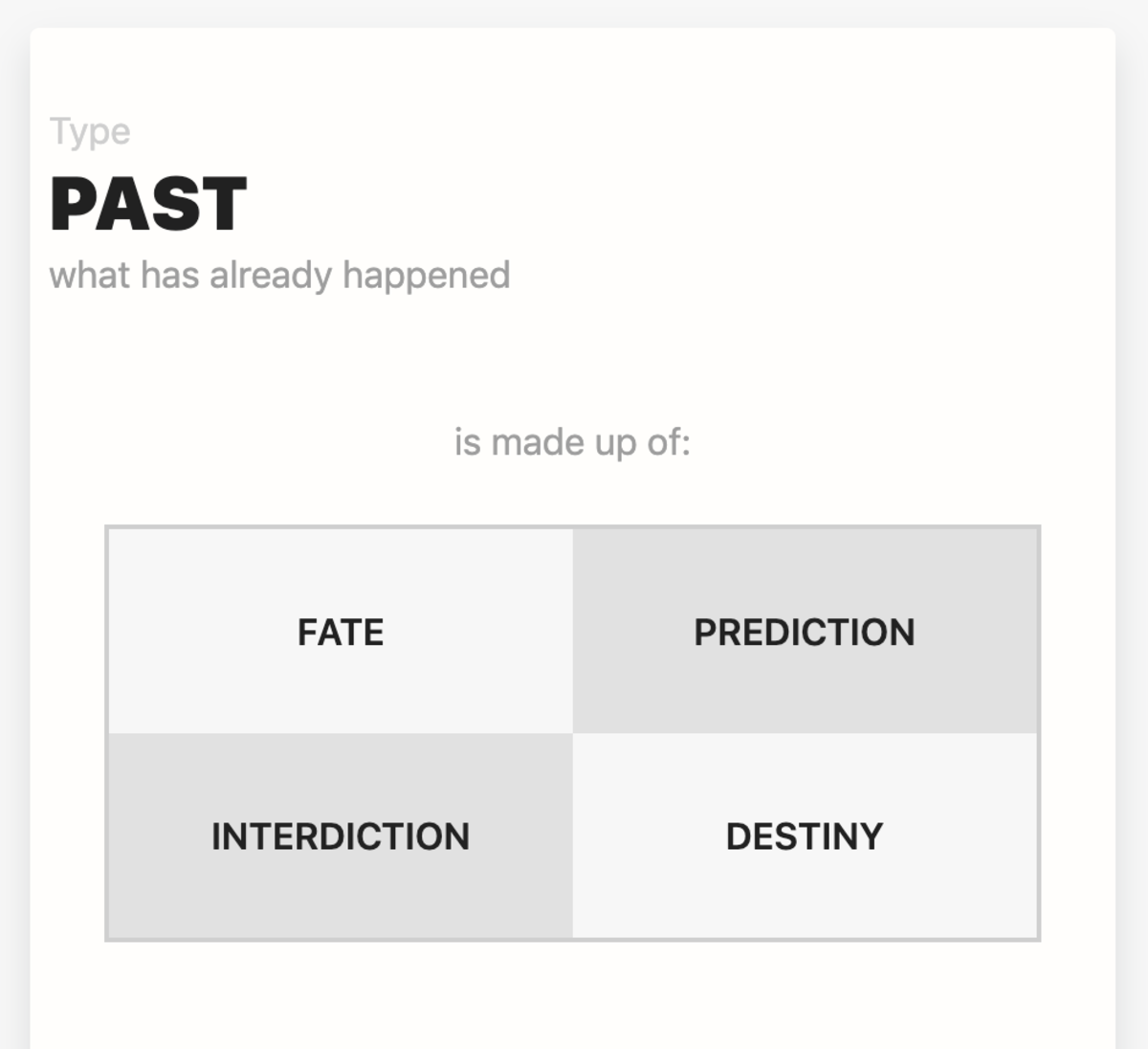

- Fate is the situation of the Past

- Prediction is the activity of the Past

- Destiny is the fixed attitude of the Past

- Interdiction is the manipulation of the Past

Down and down in greater detail for every single Element in every single quad. When you get to the bottom, you loop back to the top and start all over.

And this continues for all eternity.

Which likely explains your next point.

Motivation and the Mind

Establishing a story "mind" for your Audience is the absolute best thing you can do for them. How detailed you want to take the exploration of that mind is up to you.

Those are pretty helpful concepts when writing a novel. But the moment I push deeper into Dramatica, I face one of two situations: either it's telling me something I know works must be wrong, or the contortions required to "fit" what I'm actually writing into the conceptual framework of the various elements that Dramatica identifies becomes so baroque as to become semantically meaningless to me.

Knowing Fate to be the situation of the Past, which is itself a situation of the Universe, is a lot to consider while writing a story. Thus, my impetus for creating Subtxt. Focus on the most meaningful most significant gains from Dramatica theory so that Authors can get back to doing what they do best—write stories.

Put differently, ten novels into my career as a full-time novelist and I still couldn't positively identify the storyform for even one of my own books. Doesn't mean there isn't one, only that if you stapled it to my forehead I still wouldn't recognize it.

Inequity is the mother of motivation. Your mind fears to lose that drive by knowing what it is you want to write about while you're writing it. And it's right—without that imbalance, there is no doing, only being.

Remaining oblivious to our subconscious is everyone's superpower. If we understood it completely, it would no longer be a source of motivation. We need it to set out on new adventures.

There's another aspect in which Dramatica has been useful to me, of course: the fact that it never perfectly describes my own book as I'm writing it. This gives me avenues to explore and consider, such as "if I try to say the influence character's issue is 'Sense of Self' then that means the main character's issue has to be 'Conditioning', only I don't think the main character's issue is 'Conditioning', so how do I feel about this and does it spark ideas for changes in the story?"

In other words, you're beginning to define your subconscious.

The recognition that an issue of Conditioning doesn't fit for your story is your conscious mind becoming aware of your subconscious artistic impulse.

That is precisely the purpose of Dramatica—to bring an Author face-to-face with an objective appreciation of his or her intuition. The more you dive into this area of yourself, the more you realize you need to make some tough decisions about your story. That understanding begins to restrict some of the freedoms enjoyed by the previously hidden subconscious.

And that's why you don't want to go any farther.

But that's as far as I can take it before the model breaks down for me, my writing process, and ultimately, the stories I write.

Dramatica is a model of the mind. It can only reflect what you put into it. That breaking down process is your mind deconstructing itself—

—and for some, that's too much to ask.

The Story Engine Between Your Ears

In a perfect world, there would be an application that recalculates storyforms on the fly. Something that could follow along with your subconscious and adjust context as your intuition explores another avenue of expression. Eventually, it would require you to make some tough decisions to make sense of it all finally, but at least it wouldn't be hampering your writing process.

Of course, that application already exists.

And it's sitting right between your ears.

Again, none of this means Dramatica is wrong or that a particular analysis is wrong– after all, there's a real possibility that String Theory is a better description of the structure of the Universe than any of the other models we have despite how hard it is for us to conceptualize. But to an architect, Newtonian physics isn't simply an easier to follow model; it's the one that actually lets you design workable buildings. And in this regard, writing a novel for me is a lot more like building a house than it is describing the Universe or designing a model of a human mind solving a problem.

With that analogy, Dramatica is both blueprint and hammer. A way to sculpt your house out of the edges of your artistic impulse.

That next board you reach for is not just another piece of wood—it's a part of you.

The question is—do you want to pick it up?

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.