Writing with Methods

The cognitive functions of thematic intent

Method actors are notoriously difficult to work with on-set; always locked into character, management, and crew suffers at the hands of a great artist. Method writers—those familiar with and skilled at seeing theme as a cognitive process—only make life easier for those further down the production line. Method writing, quite literally, saves lives.

And the first life it saves is that of your story.

The most common mistake in all of Dramatica is to treat various Storypoints as mere examples of storytelling. This misguided approach is what leads many to consider working with the theory a form of Mad-libs. What one sees spelled out in Dramatica and Subtxt is the substance of story, not the story itself. It's up to the Author to go beyond what is presented and convert thematic intent into a dependable source of conflict.

When illustrating a Storypoint, you must resist the urge to write about the Storypoint. Given a Storybeat like this:

Brad comes up with an even better to live.

Many write something like this:

Brad comes up with the idea to workout three times a week.

And figure the Storybeat covered.

They continue this approach for 20-30 Storybeats, then wonder why their story doesn't seem to go anywhere.

The Method of Conflict underlying the above Storybeat is Conceiving. For that Beat to work correctly in a narrative, it must communicate how the process of coming up with an even better way to live creates conflict.

"Coming up with the idea to work out regularly" is an illustration of a Storypoint already completed—not a Storypoint in action. The Storybeats of a narrative are cognitive functions proceeding in the moment; writing them as such guarantees a flow of meaning through the narrative.

Original Terminology is Always Right

English is a somewhat problematic language. Words that mean one thing in a particular context mean something else in an entirely different space. Even those familiar with the language struggle to remember the difference between "then" and "than."

To make things easier, those that came before us broke what was already fixed in Latin—kinda like what happened to Dramatica and the attempts to "improve" upon its original terminology—and kind of with the same results. The inability to fully grasp a Method within a Storybeat is the fallout from this dumbing down of language.

This concept of the Method component within a Storypoint finds roots in the original Latin gerund. Gerunds are verbal nouns, meaning they are nouns built on a verbal base.

Gerund comes from the Latin word gerundus, which means to carry on. In English, gerunds can be the subject of the sentence, the direct object, or the indirect object, and they always end in "ing." They are verbs that are acting as nouns.

Gerundus means to carry on—appropriate when you consider the purpose of a Method within a story: to carry on the thematic intent of a narrative.

Latin gerunds are formed by taking the present base plus the thematic vowel, adding -nd- and first/second-declension neuter singular endings, for example, videndum, meaning "(the act of) seeing," or credendum, meaning "(the act of) believing."

The Method portion of a Storypoint is the act of that semantic item. It's a verb masquerading as a noun. Past is not what happened; it's the act of Past. Actuality is not what is objectively going on; it's the Act of Actuality.

Approaching a Storybeat this way guarantees a continuation of flow and life throughout the entire narrative. Using a Storybeat as Illustration is a sure-fire way to kill all momentum instantly.

Illustrating Methods of Conflict

When you see Past in Dramatica, think the act of Past-ing; when you see Sense of Self translate that into the act of Sense of Self-ing. Conceiving already contains the suffix—but add another one to make it Conceiving-ing, and you'll start to connect with how it works in creating a story.

It's not the coming up with an idea for a story that's important, but rather the cognitive process of coming up with a plan that connects with the thematic intent of a narrative.

A Main Character Throughline Storybeat of "John brings up the past" is more than merely a history lesson; it's an act of drumming up what once was that creates excellent personal turmoil for John. The maxim, "Let sleeping dogs lie," perfectly encapsulates this idea of creating conflict through Past-ing.

Same with the act of Sense of Self. "The Walters think highly of themselves" is not merely character description within an Objective Story Throughline Beat; instead, this act of thinking highly of themselves drives them to plot and scheme against those beneath them because of their air of superiority (see the excellent Knives Out).

Which brings us back to Brad, and his efforts to clean up his health game. When locked within a mental process of continually coming up with a better way to live, paralysis by options kicks in.

Suddenly, working out isn't enough.

Restrictive diets dictate what he can and cannot eat and whether or not he should add cardio to his regimen conflicts with the demands of his already packed schedule. Wanting one more chocolate chip cookie when he's already had two on his cheat day is not helping his decision-making process.

The constant back-and-forth elevates the sense of not being the kind of person who works out, and who could be relied upon to follow through on tasks. It might just lead him to quit altogether...

...which would lead Brad into the next Act of his story.

A Method to Escape the Madness

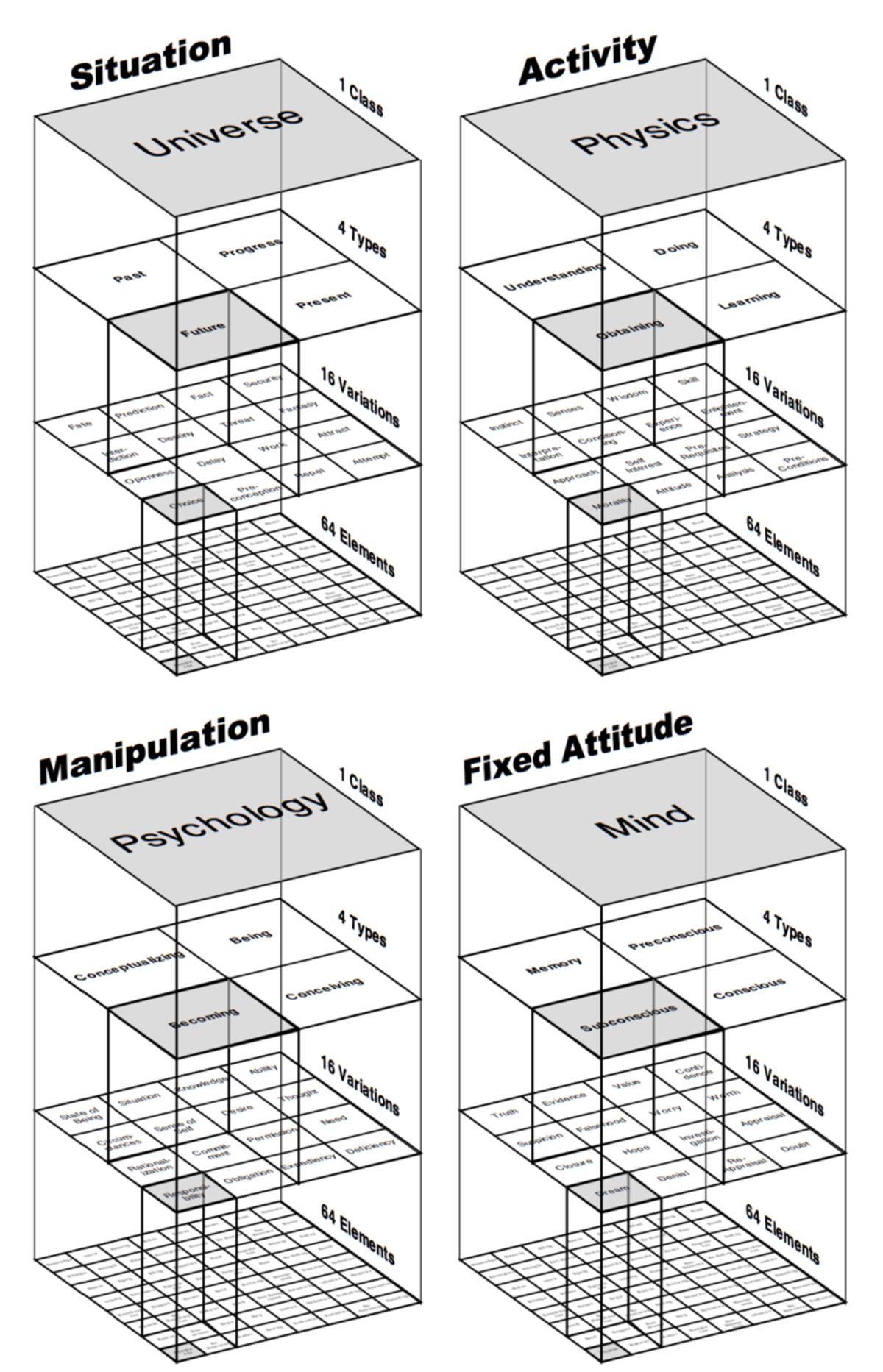

In programming, a Method is a function specific to a particular Class. With Dramatica and its Table of Story Elements, the relationship is no different.

The Classes at the top—Universe, Physics, Psychology, and Mind—classify the narrative functions below. Past is a function, or Method, of the Universe Class, as it relates to a fixed external state. Memory is a Method of the Mind Class, as it relates to a fixed internal state. Conceiving finds itself a Method in the Psychology Class, as its function within the narrative refers to an internal process of cognition.

When you start to see the various Storybeats of a narrative as self-contained mini-stories, you witness the process of narrative in action. Writing becomes a series of interactions akin to object-oriented programming, where one enters a function (scene) in one state, and returns an altered state—fit for the next scene (function).

If a complete story is an analogy to a single human mind in the process of resolving an inequity, then it only makes sense that the path through that story mimics the mind's neural network.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.