A Skeleton of Scene Structure within Dramatica

Finding fun in Dramatica's structured approach

Researching potential ways to develop scenes with Dramatica, I came across an interesting insight that I wanted to share.

In Armando Saldańa Mora's book Dramatica for Screenwriters, he explains a process by which one can use Dramatica's Plot Sequence Report to develop sequences and eventually scenes for a particular narrative.

Typically, I do this by flying by the seat of my pants. After spending so much time diving into the various structural story points within each Throughline and laying out the larger dramatic movements found in the Transits, I feel like I want my imagination and personal creativity to take over.

Basically, I want to have fun writing.

But I can see how this might be difficult for some, especially when you consider the fact that Dramatica is so specific when it comes to the ingredients of story. Why would Chris and Melanie leave out specific information regarding sequence & scene development?

An Explanation for an Oversight

The short answer is that, at that level, the interference pattern between the various Throughlines is such that if you mess up the order of the micro-events in a Scene or misplace one Scene in another Sequence, the overall message of the story—or storyform—remains the same.

This is how Finding Nemo and Collateral operate from the same storyform, yet tell that story in vastly different ways. Same with Star Wars and Birdman. Though the latter ventures on breaking form with its use of magical realism, the base storyform functions with the same collection of storypoints as Lucas' space opera.

They wanted to leave Scene Creation and Sequence Building up to the Muse of the Author. But what about those who want, or need, more detail in order to tell stories dear to their heart?

A Quad of Scene Construction

In Armando's book he speaks of True Events and False Events when it comes to scene creation. A True Event—one made of "one-hundred percent pure Dramatic change"—consists of four base elements:

- It's irreversible.

- It changes the characters' circumstances.

- It gives the characters new and more important purposes.

- It's meaningful to the characters (and, therefore, to the Audience)

Reading this again recently, it struck me what quad these four elements came from:

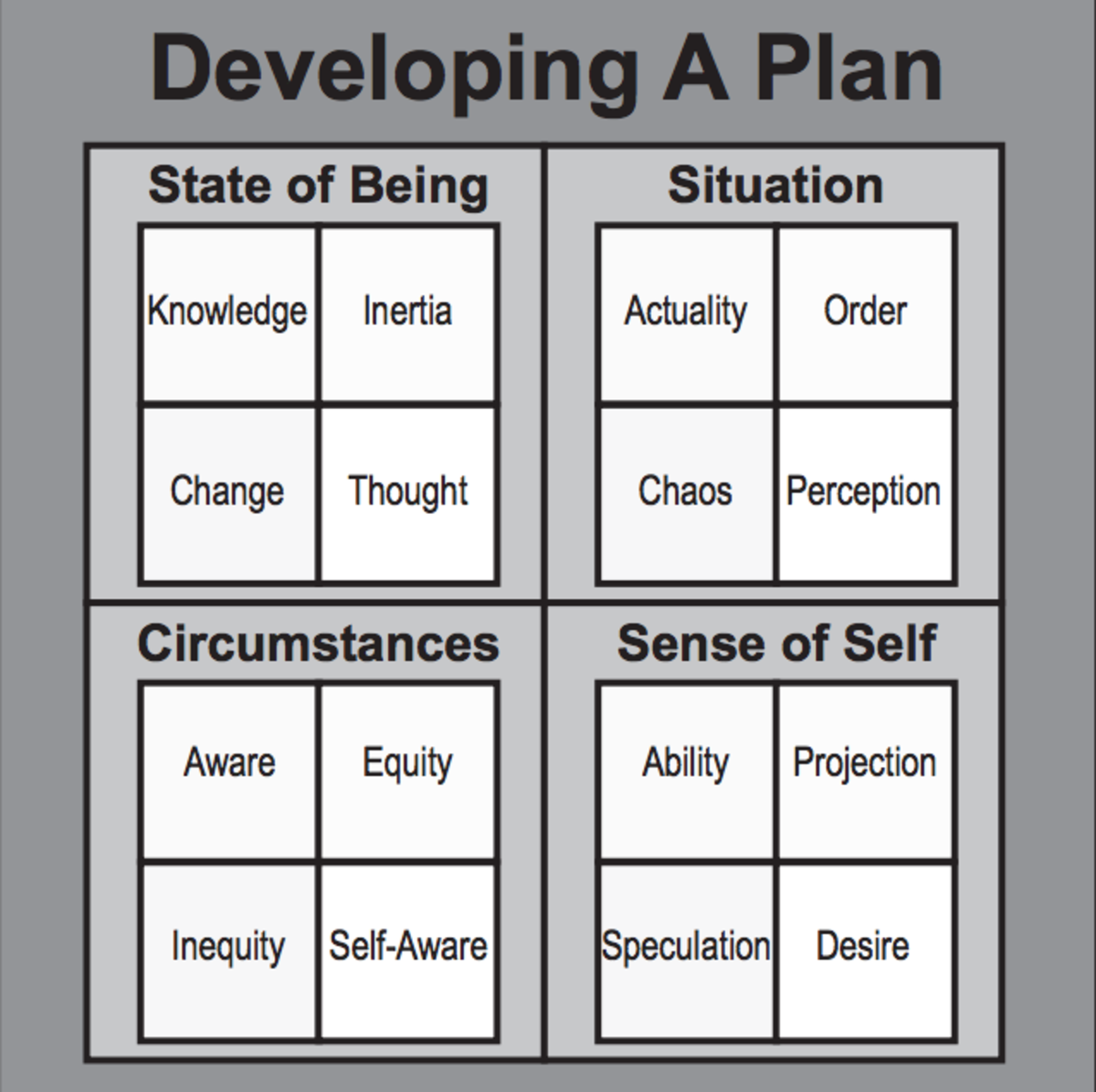

Irreversible? That's Universe under Conceptualizing.[^concept] Changing the Character's Circumstances Well that's clearly Circumstances. New and Important Purposes? Probably gives someone a new Sense of Self. And finally, Meaningful to the Characters…that gets to the essence of the characters, or their State of Being.

And when you consider Sequence-based writing methods like The Mini-Movie Method that ask Authors to imagine What is the protagonist's plan? or How does he plan on getting what he wants? or What new plan does he or she come up with?, it only makes sense that the issues sprung by inquiries of this nature would be Universe, Circumstances, Sense of Self, and State of Being.

Extrapolating the Concept

Directly across from Conceptualizing we have Conceiving—which consists of the ever popular Needs and Wants of a character (Need and Deficiency respectively).

Advocates of the Needs and Wants Committee for Writing a Story often leave out the other two—Can's (or Cannot) and Should's (or Should Not), but they're equally as important when seeking out the drive or intent of a character within a scene.

Thought, Knowledge, Ability, and Desire probably speak of the storyform itself, or the motivation of narrative driven by the storyform.

And Responsibility, Commitment, Rationalization, and Obligation call to mind the development and transformation of character from scene to scene.

More on this as it develops.

[^concept]: Or Conceptualizing if you prefer the original terminology from '94 (I do).

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.