Dunkirk

A missing Throughline turns this historical account towards propaganda.

A complete narrative examines conflict from all points-of-view. Through the four perspectives provided by the Objective Story Throughline, the Main Character Throughline, the Obstacle Character Throughline, and the Relationship Story Throughline, the Author grants special insight to the Audience not available in their day-to-day lives.

We can’t simultaneously be both within ourselves and without; in a story we can. We experience conflict from within through the Main Character’s personal point-of-view and we experience conflict from without through the Objective Story Throughline’s perspective. With both objectivity and subjectivity present, greater meaning rises from the text.

In Dunkirk, that greater meaning appears to propagandize Britain’s ability to survive during the opening years of World War II.

Positive Propaganda

The Dramatica theory of story casts no judgment on the use of propaganda within a narrative. Manipulating an Audience to think one way or the next can be a good thing, or it can be a bad thing. Publishing news adverts that demean the Jewish population in Nazi Germany was a bad thing. Michael Moore’s Sicko coerced a segment of the population into seeing the benefits of a national health care system and was a good thing–if you stood on that side of the argument. If you felt national health care detrimental, then you saw the film negative in its manipulation.

Propaganda is propaganda, regardless of position.

This is why the Dramatica theory of story reserves no room for arguing good or bad when it comes to technique.

Instead, it gives a reason why the propaganda works and explains how an Author can combat it–assuming manipulation is not the original intent. Bong Joon Ho’s Okja functions as propaganda against the eating of animals because that was the purpose of making that film.

Christopher Nolan’s purpose for Dunkirk appears to be extolling the virtues of British resiliency.

The Mole. The Sea. The Air

Whether on land, at sea, or in the air, the citizens of the United Kingdom find themselves trapped in difficult and problematic Universes. With their backs against the sea, the soldiers on the beaches of Dunkirk see no way out. They stand in line and await their turn as the next victims of German dive-bombers.

Those public citizens commandeered by the Royal Navy to cross the channel and bring back their army also find no room to escape. If not now, then the future promises their own enrollment in the conflict to come.

Finally, the pilots above find themselves servants to both the realities of air-to-air combat and their unique position to make a difference in the lives of those below. Fixed amounts of fuel and dwindling ammunition give little room towards free agency–forcing those in the air to make difficult decisions in impossible situations.

The Objective Story Throughline covers the conflict They experience within a narrative. By standing back and observing actions and decisions through the lens of objectivity, an Audience appreciates a broader perspective and a greater understanding of the events of the day.

The Subjective Argument

To counteract and counterbalance the objective argument present within the Objective Story Throughline, the Author turns to the subjective view available within the Main Character, Obstacle Character, and Relationship Story Throughlines. In Dunkirk, the Obstacle Character Throughline stands out as most prominent.

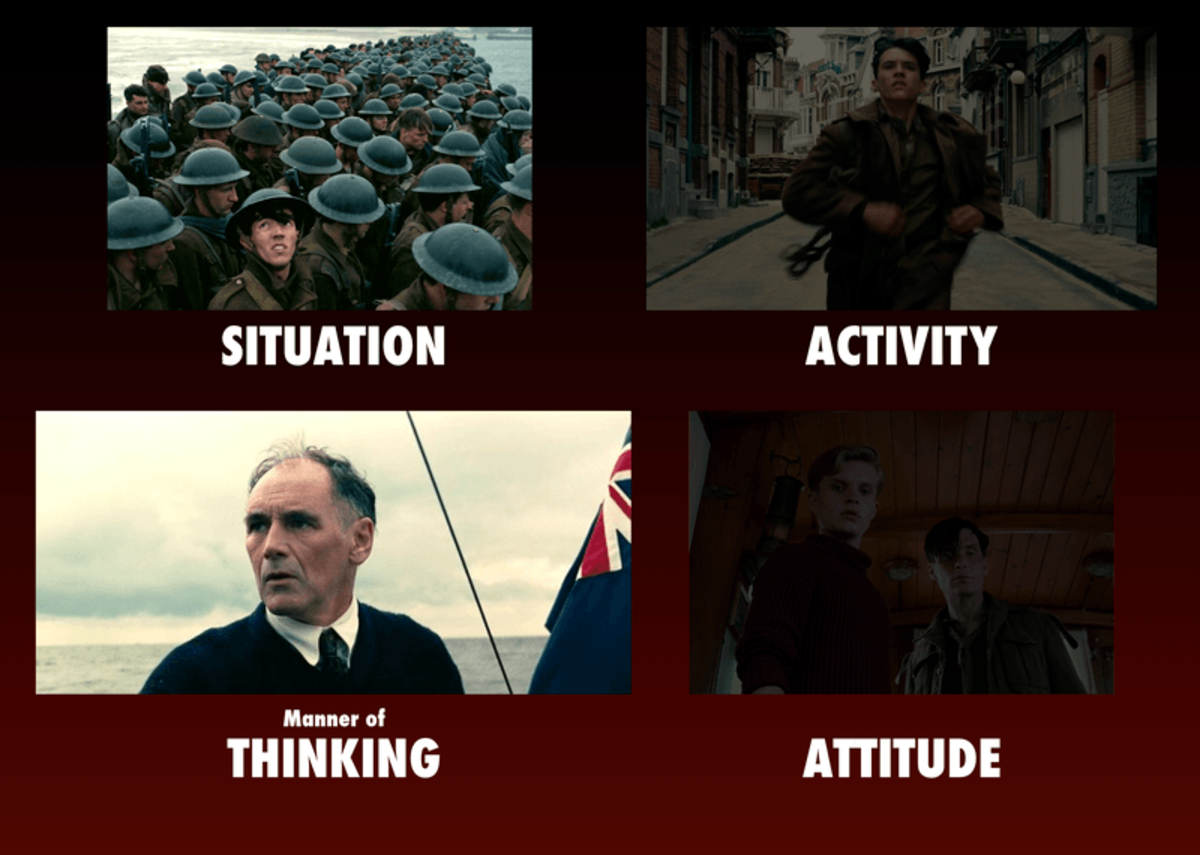

Ship captain Mr. Dawson (Mark Rylance) demonstrates that British resiliency from beginning to end. As Obstacle Character, Dawson impacts and challenges those around him through his unique Manner of Thinking. Conceiving no other alternative than to forge ahead, Dawson embodies the Royal motto Keep Calm and Carry On. This approach proves to be the key to survival for the British people–as reflected in Churchill’s speech at the end.

Unfortunately, this argument breaks down as we dive further down into subjectivity.

The Main Character and the Heart

Candidates for Main Character abound.

Soldier Timothy (Fionn Whitehead) grants us that first-person perspective from beginning to end. The Physics he engages in, from running away to making a stand in the hull of the beached ship dictate his growth of character.

Yet, he fails to engage in any meaningful relationship that could be considered the Relationship Story Throughline.

Mr. Dawson’s son Peter (Tom Glynn-Carney) also shows growth in character through his adoption of his father’s certainty–yet his problematic Physics amount to very little on the ride over.

To further complicate matters, Peter’s acceptance of the Shivering Soldier (Cillian Murphy) functions as the appropriate resolution for the Relationship Story Throughline–yet seems to resolve that objective relationship rather than the subjective one present between father and son.

A One-Sided Argument

As with Inception, Christopher Nolan dials up the Objective Story Throughline at the expense of the Relationship Story Throughline. The result is a lack of heart and in this case–an increase in the narrative technique of propaganda. By “missing the boat” on constructing this essential component of narrative, Dunkirk excites and informs, but does not enlighten.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.