The Science Behind Dramatica

The definitive explanation of the magic behind the theory

Hubris is defined as "excessive pride, or self-confidence." In this series, I match hubris with hubris in the definitive defense of what I consider to be one of the most important narrative theories of all time.

Dramatica and a Narrative Model of the Mind

Setting the record straight

Knowledge is the basic building block of logic. Once we know something, we can easily combine it with other bits of Knowledge to form a conclusion—a new block built upon the foundation of the earlier ones. When productive, these blocks of Knowledge manifest a higher level of thinking; when deleterious, those entrenched in beliefs can’t find their way out.

Those blocks only lift them so high.

There exists a post: Opinions, Questions, and Hunches on Dramatica Theory that haunts me every time I visit the Screenplay forum; not for any threat to my life’s work, but rather because of the sheer magnitude of ignorance it conveys about the theory. Even worse, it tends to infect the minds of others:

I rather like some aspects of Dramatica theory, but the more I dig in the more inconsistencies I find. Someone else posted an absolutely devastating critique on its lack of formalism.

Only it’s not “devastating.” And the lack of formalism is the result of a lack of proper research. And the inconsistencies?

Guess it’s time to address this madness finally.

The author behind the post spent zero to little time educating himself about the theory. Same with anyone else who, blown away by the sheer volume of the response, assumed their confusion was the rule.

We find this all the time with Dramatica: an individual’s inability to grasp the concepts leads him or her to set out on a course of willful destruction. Much easier to kill what we do not understand. The retort, while seemingly impressive by length and challenge, is merely fearful ignorance masquerading as thoughtful critique.

The Basics

The first misunderstanding is that of context. Meaning is context. What might be right in one context ends up bad in a completely different scenario. A knife is meaningless unless used for cutting and preparing a meal; it’s even more meaningful when used in a murder. The prior context is a good use of a knife, the last bad—assuming crime is terrible. Sometimes, it’s an entirely acceptable form of behavior.

Context determines meaning.

Now, the purpose of a Grand Argument Story is to imitate a human mind experiencing and tackling the problem from each and every possible scenario.

Wrong. The purpose of a Grand Argument Story is to communicate one possible scenario—one singular context.

Tackling every possible scenario from every possible context is a recipe for madness. If you want that, live your life; we swim in a constant sea of turbulent contexts, ever-shifting given the present moment.

A story is not that; a story is one moment.

Dramatica imposes a limit by only allowing the combined dimensions of position and motion (resulting in the four members of the Class quad) to be used only once throughout all viewpoints.

This limitation is a feature. This imposition of combinations prevents one from running around in circles and chasing one’s tail of consideration (see your post). If everything means something from every context, then everything means nothing.

When it comes to identifying a Source of Conflict for a Throughline, many tend to focus on one point-of-view to the exclusion of others. They look at Andy Dufresne in The Shawshank Redemption and see his problem in all four Domains:

- Universe: an innocent man locked up for a crime he didn’t commit

- Physics: a rebel who stands up to physical aggression

- Psychology: a man on a mission to change the way a prison population thinks

- Mind: an optimist who suffers at the naïveté of his hopes and dreams

But what does all of that mean?

Now, look at Andy in the context of the other three Throughlines, and you begin to see what the story is all about:

- Universe: an innocent man disrupts the stasis of corruption at a prison

- Physics: a rebellious freedom fighter stands up against any physical aggression

- Psychology: an institutionalized man supports the system (Red)

- Mind: a friendship develops around the idea of hope

Seen in this one instance, it’s clear that Andy doesn’t even represent the Main Character I perspective—Red does. And it’s even more apparent that with all these perspectives encapsulating a single inequity, that there exists a way out. The Shawshank Redemption argues that finding freedom and triumph requires abandoning the support of external systems—and it does this by presenting one set of interrelated perspectives.

Trying to witness it all at once: the relationships, the personal perspective, and the influencing points obliterates any recognizable meaning. We find ourselves lost at sea again, adrift in the ups and downs present before the introduction of Dramatica.

So, to answer the first question:

1.Why does Dramatica impose this limit? Shouldn’t each viewpoint have a problem in each member of the Class Quad in order to have a Grand Argument Story?

No. Viewpoints do not “have” problems—they create them. Problems are something made up in our minds; the moment we look at an inequity from a specific point-of-view and declare it a problem, well—its now a problem. That inequity, or separateness, is not truly a problem, our appreciation of it as a problem makes it a challenge.

That process of justifying inequities as problems is what Dramatica models with its Table of Story Elements.

Switch the perspective, and you switch the context; change the context, and you change the meaning.

A storyform in Dramatica represents one meaning and, therefore, one context.

The Basic Concepts Underlying the Dramatica Theory of Story

The formula for predictive psychology

Obfuscation is not always an attempt to mislead. Sometimes, not revealing what's inside the box motivates another to seek out for himself what lies inside. Whether or not one finds something inside relies entirely on that individual's ability to open the box without cutting himself.

Some even give up long before that.

In a ridiculously long post, chemical engineer Goose posits:

I scoured Dramatica Theory and the internet looking for more information or clarity to no avail. This experience leads me to believe two things: either the theory is sound, but is just presented poorly OR the theory is not sound, and the writers compensate by making things vague and confusing (either consciously or not).

The first is accurate, with a dash of the second thrown in for good measure. Dramatica theory is sound, but presented poorly on purpose—the vague and confusing nature obfuscates the specific algorithms and relationships that make up the "special sauce" of Dramatica.

1993 is not 2020. The year of Dramatica's original release knew nothing of open source software or the possibilities of expansion available within the sharing of information. Protection and copyright motivated a modus operandi of keeping those theoretical concepts under lock and key.

Dramatica Theory spectacularly conceals or ignores most of its assumptions, axioms, and logical processes related to the creation and application of the model.

Yes, this is true. The concealment was a factor of both finance and nurture. Growing a revolutionary theory at the outset requires protecting the very nature of its underpinnings. Explain enough of the method to put it into practical use, but don't reveal all for fear of losing everyone right out of the gate.

While some of the questions asked stem from obfuscation, many signal an inability to think soundly about the nature of inequity and perspective.

Imagine the fear and panic if the totality of all remained on the table.

The definitions of words give little indication of what the word represents in the model logically, or the reason for its particular placement.

This problem I can explain.

Dramatica's original pitch targeted Hollywood. Revolutions require funding, and at the time, Software as a Service systems did not exist. Story theorists and amateur writers were not known to be venture capitalists; the closest thing to seed money were the aspirations of Hollywood's best writers.

Those writers want terminology and definitions closer to how they think and speak in the day to day operations of their work. They don't want to hear about Universe or Prerequisite or Deficiencies—and they certainly don't want to hear that every single quad is the same four Elements:

They just want to know what should happen during the second half of the Second Act.

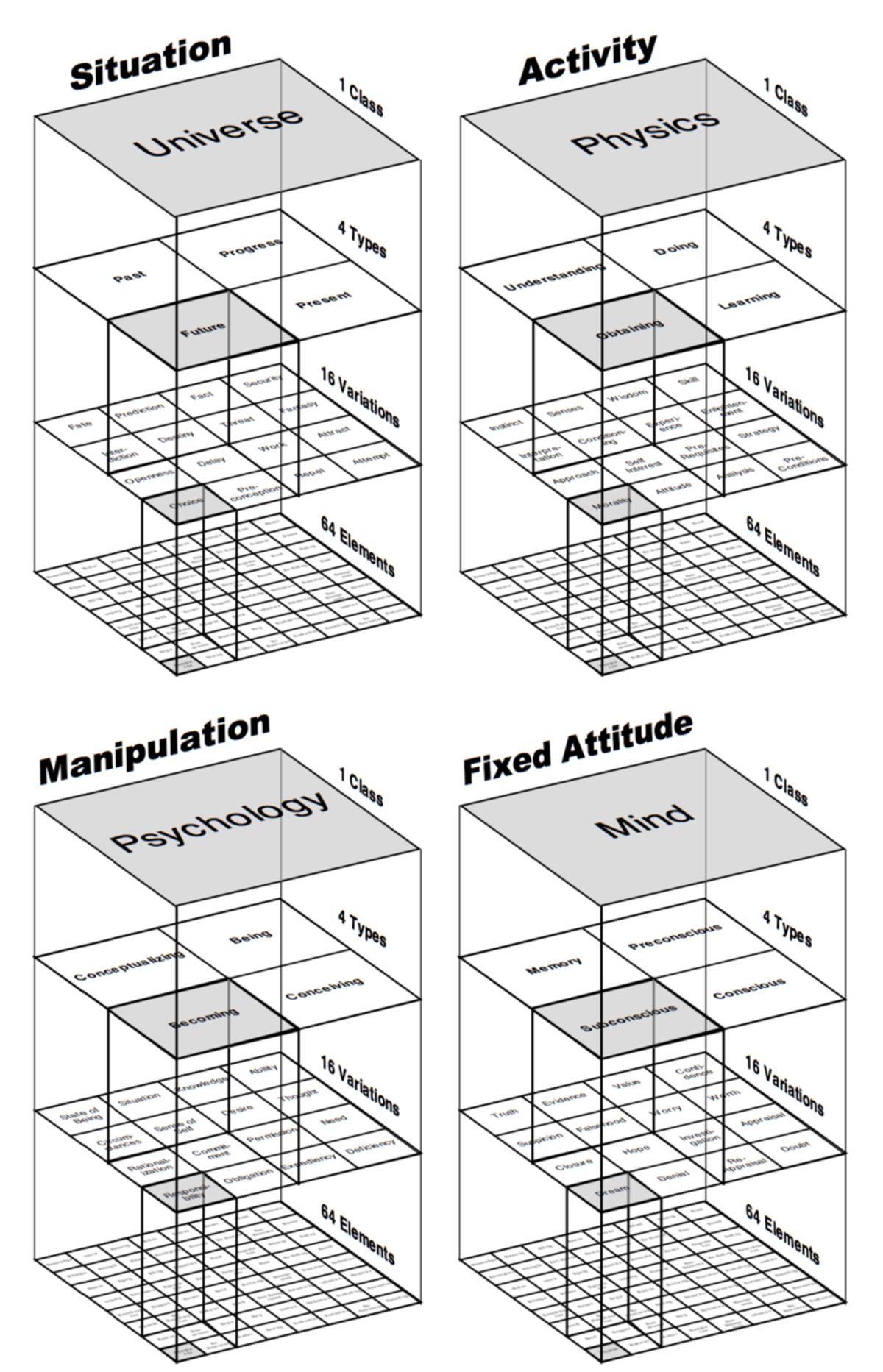

The Base Quad of Dramatica

Dramatica models the human mind processing an inequity. Part of this process involves categorizing that inequity through the lens afforded by the mechanism of the mind. In other words, we see problems as a result of our minds—problems exist within us, not without.

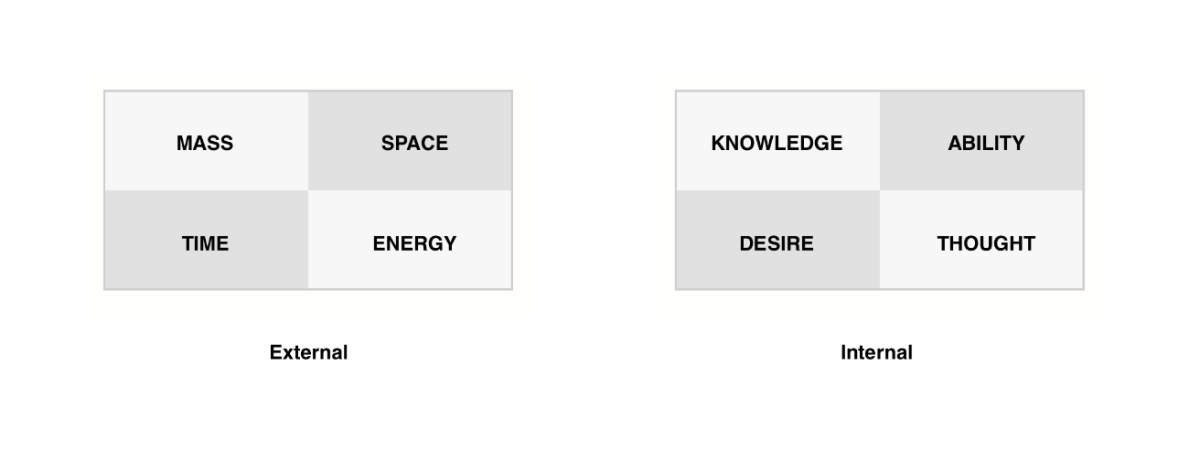

We perceive four bases outside of our minds:

- Mass

- Energy

- Space

- Time

We perceive only these four as a function of our mind's internal bases:

- Knowledge

- Thought

- Ability

- Desire

These two groups correlate with one another, such that:

- Mass is Knowledge

- Energy is Thought

- Space is Ability

- Time is Desire

We see Mass because of Knowledge; we appreciate Energy as an external representation of Thought. Ability and Desire are often harder to see as Space and Time until you understand strengths as the spatial relationship between chunks of Knowledge, and desires as Thoughts that evolve over Time.

We make our world, seeing the Universe as we are, not as it truly is.

And that's precisely how we write stories.

Dramatica just makes it easier to understand how it all works together.

The Mental Math Behind the Theory

The magical feature of Dramatica is its ability to predict Storybeats within a story. Given a set of Narrative Dynamics and a focal point of consideration, Dramatica outlines the steps needed to progress from beginning to end. That story you've been struggling to write for three years? Dramatica helps you cut that time down to three months—including the final product.

This ability to predict narrative lies in a mathematical equation that many find themselves already familiar with every day.

A quad has four corners occupying a square. In accordance with the theory, we give the symbol "A" for the top left that represents "external state", "B" for the bottom right that represents "internal state", "C" for the top right that represents "external process", and "D" for the bottom left that represents "internal process". For example, in the topmost Class stage, A = Universe, B = Fixed attitude, C = Activity, and D = Psychology.

It would be easier to replace these with Dramatica's four base Elements of Knowledge, Thought, Ability, and Desire—but I present both to continue the conversation:

How are A, B, C, and D related? I remember reading something about a pseudo-mathematic equation of A/B = CD, which supposedly means that "when A and B are separated, then C and D are blended" or something.

Yes, this is correct. While not strictly a mathematical equation in the Male sense of 2 + 2 = 4, the idea that one side of the quad dividing balances out with the other side multiplying (blending) holds true in a Holistic sense.

We are talking about the mind here.

The equation does not make sense to me. I do not understand the logic or the apparent psychology behind it.

For a second, let's transpose our perception of the Universe onto Dramatica's base quad of Elements:

And now let's take these observable bases of the Universe and graft them onto Dramatica's equation that is "supposedly" mathematical:

M/E = S*T

And now, let's solve for E:

E = (S*T) M

Hmm. I think I'd like it better if I move the M in front of the S and T...and you know what? S and T are just the same things—a constant, if you will—so let's write the equation out like this instead:

E = mc2

Look familiar?

Einstein blends Space and Time into a constant because that's what a Male mindset does with Ability and Desire—it combines them such that it becomes difficult to think of them as separate.

Ever ask a Male thinker to explain his feelings? Ever wonder why he wants something so badly, yet the moment he has it, he no longer wants it anymore?

That's why Einstein blended Space and Time into a constant.

And that's how Dramatica predicts the Storybeats of a story.

A Model of Relationships

When dealing with the relationships between items in a given context, a conceptual understanding of mathematics helps to describe the elements within a function.

2.What's the deal with the equation A/B = CD? How is it that when an "external state" is separated from an "internal state" that an "external process" will blend with an "internal process"?

Dramatica is a model of relationships. As much as the Male mindset would prefer this relationship to be strictly cause and effect, experience requires something much more comprehensive.

When looking at one Method within a quad of Methods, one must appreciate all four at once. To isolate one or two to the exclusion of others is to obliterate any utility from the Method. When considering the quad of Methods underneath Universe, Past and Present are seen as separate, whereas Progress and Future appear blended. You never know where one starts, and the other begins.

Dramatica mainly focuses on the relationships between A, B, C, and D of a quad through Dynamic, Companion, and Dependent Pairs. The Dynamic Pair states that the diagonal items in a quad contrast the most. So, "A" representing "external state" is most opposed to "B" representing "internal state". The "C" representing "external process" is most opposed to "D" representing "internal process". Therefore a Dynamic Pair contains items of the same motion (state) but different position (external and internal).

You conflate the essential properties of a Dramatica quad with contextual references of dynamics (motion) and location (position). One is not "in motion" (process) and another not (static), any more than light is either a particle or a wave. Both exist simultaneously, the perspective from which one appreciates the quad defines their "motion." Same with external and internal—they both live at the same time in what many refer to as projection.

How do the logic of Dynamic, Companion, and Dependent Pairs make sense according to motion and position? Why is an "external state" most opposed to an "internal state" instead of an "internal process"? Am I way off with this motion/position thing?

Yes, way off (see above).

The current model is Knowledge-based. This bias implies two things: a) Knowledge sits in the upper left-hand corner of the quad, and b) appreciable meaning is a function of Knowledge.

You need a bias when searching for meaning, a context from which to understand up from down. The original version of Dramatica chose Knowledge as its given as that bias more closely aligns with Western Male thought.

In the West, you either Know it, or you don't.

Your giant post of Opinions, Hunches, and Thoughts about Dramatica is an example of what it's like to be blinded by Knowledge. Assuming your place of origin to be somewhere in the West (99.999% sure), I see example after example of someone justifying a line of questioning from a basis of certainty.

One of these biases is the assumption of opposites. To you, a light switch is on or off—you fail to the dynamic transition between on and off.

Part of this preconception can be seen in your assumption of motion and position (moving, yes or no? Inside or out?), but it also appears in your misunderstanding of what it means to be a dynamic opposite. To you, antithesis is a function of on or off, not a more comprehensive appreciation of relationships between items.

If what I assume that what I Know is indeed true, then my Desires are not the dynamic opposite of that Knowledge. The two might exhibit Dependent behavior with one another, but they exist in tandem. Some Know the world to be flat. This Knowledge is a tremendous source of happiness for them and draws them to want to be with others who know the same. Dynamic conflict is not present in this relationship—Knowledge is an external state of mind, Desire is an internal process.

Likewise, if what I assume to Know is true, then my Abilities only serve to amplify or diminish that Knowledge. Knowledge and Ability are Companions within the mind. Kobe Bryant knew he was the best from the age of six. His natural talents (Abilities) only amplified that Knowledge, taking it to a level unheard of in professional basketball (the Black Mamba moniker). And that Knowledge drove him to remove the Ability for other players to touch the ball. Both Knowledge and Ability worked in tandem within Kobe to make him one of the greats.

Dynamic conflict is not present within the relationship between Knowledge and Ability—Knowledge is an external state, and Ability is an external process of the mind.

Knowledge and Thought, however, are directly opposed—especially when Knowledge is assumed to be true (re your post).

You Know static and process to be a function of motion, yet when presented with a different way of Thinking about them, you spend hours and hours writing the ultimate shaggy-dog post of a question. Your criticism is Dynamic Conflict manifest—a result of an external state of the mind Knowledge clashing with an internal state of the mind Thought.

Thought is not a process; one thinks or thinks not.

Knowledge and Thought in the mind collide the same way that Mass and Energy do in the universe. Direct enough Energy and you can shatter a seemingly impenetrable Mass.

The same process occurs in the mind: you may Know something to be impenetrably true—but direct enough Thought towards it, and you can burst through those preconceptions.

But not all Dynamic Conflict is deleterious; Knowledge and Thought combine to manifest even greater Knowledge in the same way that iron sharpens iron:

As iron sharpens iron, one man sharpens another (Proverbs 27:17)

Pretty much describes this additive result of conflict between Knowledge and Thought. This article and the hundreds before it sharpen the iron of other writers.

Conflict is not a function of opposites. When Knowledge is taken for granted, the most significant source of conflict for it is Thought. Abilities and Desires work in concert with Knowledge, supporting through companionship and dependencies.

The Restrictive Size of a Mind

Developing an accurate model of the mind requires an appreciation of scope.

I also do not understand the recursive nature of quads. Based on Dramatica, it seemed clear to me that the quads simply got smaller and smaller within each other. So, the top right item of the Class quad could actually be subdivided into a whole new Type quad, and then the Variation quads, and finally the Elemental quads containing 256 items total (though only 64 unique ones). Why do we stop at Elements and not go further?

We stop at the Elements because of what Dramatica refers to as the Size of Mind Constant. When holding a single context, our minds perceive seven items, plus or minus two. Miller's famous 1956 article "The Magical Number Seven" describes this observation of short-term memory:

people's maximum performance on one-dimensional absolute judgement can be characterized as an information channel capacity with approximately 2 to 3 bits of information, which corresponds to the ability to distinguish between four and eight alternatives.

The Dramatica Table of Story Elements and its four levels of magnification represents the totality of what our minds can retain all at once. You can dive deeper into the Elements—but then you lose sight of the top. Practically speaking, this is what happens within a television series. The series itself tells of one story, while the individual seasons and sometimes episodes explore those Elements as if they were their own story.

Consider both the quad of Mass, Energy, Space, and Time and the quad of Knowledge, Thought, Ability, and Desire. Now, stand on one as a given from which to appreciate the others—and you see evidence of Miller's law beyond pure coincidence.

Why are the Elements the building blocks of this model? It is not entirely clear to me, but I assume it has something to do with balancing the idea of "four" in the model.

Assuming the Elements to be the building blocks is a spatial misinterpretation of the visual representation of the Dramatica model. The Elements are not the "foundation" of the towers. Those towers are a misrepresentation as well—the actual model is collapsed in on itself—a singularity of the mind.

I initially thought that maybe the Elements were the building blocks because at that point our four towers of quads (Universe, Activity, Psychology, and Mind) converged. Once we got to the Element stage, all of the sudden our items in the quads repeated. In fact the 64 Elements generated in one Class are the same as the Elements generated in another. But wait, why do the 64 elements repeat at this level? There doesn't seem to be a reason for it (more on this later).

Those repeated 64 Elements should indeed be 256 separate Elements. Two reasons why they are not: 1) if they were distinct, Authors would undoubtedly miss the connections between subjective and objective points of view, a vital aspect of wrapping one's head around the Premise of a story. 2) define the difference between Pursuit in the context of Physics compared to Pursuit in terms of Psychology. Compound that with a different word for Pursuit within a framework of Universe, and another within Mind. An intellectual exercise to be sure but one that most likely would not be worth the effort.

The quad has four items (from the motion and position dimensions) and there are four viewpoints; therefore, everything must be four in order to maintain balance. The model must only have four levels of recursive quads. This may have been exacerbated by the four established literary terms: character, theme, plot, and genre.

Not exacerbated—corroborated. Validated. The idea that for centuries, we naturally subdivided narrative in terms of character, plot, theme, and genre only supports the concept that we see the world as we are, not as it truly is. Stories are a reflection of how we think-and Dramatica models that process.

But desire of balance is not a logical argument, but instead a satisfaction of our psyche.

Exactly!

Einstein desired one equation to describe the Universe, but that doesn't mean one exists.

I agree. The question to ask yourself is, how can we possibly describe the Universe with one equation if the very tool we use to describe it is hampered by three-bit technology?

We can't.

So instead, we write stories.

The Bias of the Current Dramatica Model (2020)

Wrapping your head around your head

Nothing means nothing until you assume a frame of reference. The sky is “above” the Earth unless you stand on your head. This same reality of psychology applies to stories and story structure. A Goal is meaningless except when placed in an objective context and paired with a Consequence. Without context, we fall into the trap of not understanding one another.

The Consequence of misattributing concepts of Dramatica is even more disastrous.

In the previous article on this series on The Science Behind Dramatica, I addressed this question:

4.What is the logical reason that Elements are the building blocks? Why not go down further recursively from Class? Or stop earlier?

Stopping earlier would result in an incomplete exploration of the mind. Going down further would only shift the scope of consideration. The Size of Mind Constant is immutable; you can’t hold more than four levels at once in a single state of awareness.

I decided to map out the recursive nature of the four levels of quads (Class, Type, Variation, and Element) in hopes of discovering a pattern.

An approach with an appetite for disaster—especially since you lack the basic understanding of the relationships between items in a quad. You can’t merely replace the labels with “ABCD” and hope to ascribe some relative meaning from them.

I stripped away the vocabulary used in all the quads and instead used only what I knew (or had assumed) of quads: that they contain a certain motion and a certain position.

This technique is why your exercise ended in disaster. Motion and position are your misinterpretations of the Dramatica quad structure; it’s no surprise your recursive journey ended in an overflow error.

Choosing a Bias to Model

As mentioned earlier in this series, every quad in Dramatica consists of the same base four Elements:

In the Super Class of Knowledge, where Knowledge is the reference point for all other considerations, the Class-level Domains transpose:

- Universe for Knowledge

- Mind for Thought

- Physics for Ability

- Psychology for Desire

A Super Class of Thought or Desire would find an alternate set of semantics for a Class level appreciation. As Melanie Anne Phillips explains in her post “Illegal” Plot Progressions

The model of the Story Mind as seen in Dramatica is called a “K-based” model, because it sees everything from the perspective of Knowledge, rather than Thought, Ability, or Desire. You can see that this is the case because there are no words like “Love,” or “Fear” in the model. These words would be in the “Desire” realm.

As the sole developer behind Subtxt, I can tell you that attempting to encode the latter “Desire” realm would be nearly impossible given current technologies. This difficulty is why Chris and Melanie defaulted to a Knowledge-based system for the first iteration of Dramatica. The other, and more important, consideration Melanie explains:

Why did we choose a K-based system? Because our primary market – American Authors – works within American Culture. That culture is almost completely K-based. Which is why most rooms have four straight walls, why language is linear, why products are put in boxes on shelves, why definitions are important, why contracts are created, why laws exist.

To a K-based culture, observable reality takes precedence over experiential subjectivity. The Universe is a constant proven by scientific observation. The Universe is what we Know. Physics play a part in describing the Universe process and, therefore, assume a Companion relationship with Universe. Physics describes the Abilities of the Universe.

Note the reference of Abilities in the Universe context; Universe is our chosen bias for this model. All items exist with that initial bias.

Psychology, or how we think, is something we can’t observe directly and is, therefore, something we can’t Know for sure. Psychology is something hidden, a dark art for one more comfortable with matters of yes or no.

This construction process of thoughts is entirely dependent upon the Universe; we envision models of Psychology that mimic and depend on our understanding of the world around us (see Dramatica, and its concept of Mental Relativity, and Einstein and his concept of General Relativity). And the Universe is dependent upon Psychology to make it a reality.

From this Knowledge-based point-of-view, Desires are a blob—“feelings” that are ultimately impossible to quantify. Desires rely on Knowledge just as much as Psychology relies on the Universe.

Lastly, and likely the most important given this conversation, is the Domain of Mind. When Knowledge is as indefatigable, our Minds deceive us, working against us to tear down what is right. How can Santa Claus continue to be known once we start thinking that Mom and Dad stay up late on Christmas Eve? Cognitive dissonance, a state of Mind, is the ultimate monkey wrench for any assumption. To have a better Mind is to think through prejudices, opinions, and “hunches” to unravel one’s limiting Knowledge-base.

Thought is the destroyer of worlds, in the same way that concentrated Energy shatters even the most stringent Mass. When Knowledge is known, Thought sits in direct opposition, functioning as Antagonist—the anti-thesis to one’s beloved thesis.

The Mind unravels the Universe.

Addressing the Recursive Nature of Dramatica

Down the endless rabbit hole of a narrative model

The attempt to unravel a complex psychological model without the key is a fool's errand. Guessing at relationships and substituting placeholders for concepts remains the only alternative for one given to such an adventure. The best thing to do when faced with the situation is to find a competent and knowledgable guide.

Throughout this series of articles on The Science of Dramatica, one limiting trend prevails: the rationalist's penchant for classification:

How does Dramatica code the relationships of recursive quads into vocabulary words with specific definitions? How exactly do the four Types’ definitions, for example, logically or mathematically exist in a Class?

As explained in the previous article, The Bias of the Current Dramatica Model (2020) every Dramatica quad is a reiteration of Knowledge, Thought, Ability, and Desire—from a Knowledge-based point-of-view.

When looking at the Universe from this perspective, the Past is what is Known. The Present is what is Thought of as the Universe. Progress describes the Ability of the Universe, and Future describes not what will be— but what is already there waiting for us as an extension of the Universe. Within the context of the Storymind, the Future and the Past exist simultaneously dependent on each other as a means of establishing their “place” in the Universe.

Let’s assume that Dramatica indeed has some secret code that changes A, B, C, or D into specific vocabulary words that all makes logical sense.

It does.

But there is another problem. According to Dramatica, the code AADB, BACB, CAAD, and DABB all code for the Element, “Desire,” with the same definition. How is that possible? Taking the only information about quads we had (motion and position), we end up with one word seemingly describing four completely different Elements. Using my recursive techniques, each one of the 256 Elements should be different, otherwise they were not derivative (or did not share the same properties) as the original quad. How did Dramatica condense certain codes all into the same meaning?

By reducing Dramatica’s relationship of quad dynamics to “ABCD” and misattributing them to “motion and position,” you lose any opportunity to understand Dramatica effectively.

As Melanie Anne Phillips explains in her book, Dramatica: Inside the Clockwork:

The Elements are the same names in each Class because they represent the basic truths in the story. They are in different arrangements because each Class looks at them in a different way.

Melanie continues to describe how the bias towards state (Knowledge) remains from top to bottom:

At the Class level, external items rest in a horizontal alignment (Universe and Physics):

At the Type level, the external is diagonal (Doing and Obtaining):

At the Variation level, the external is vertical (Approach and Altruism):

Having worked our way through all the available permeations, we reach the bottom only to be left unable to distinguish external from internal:

But we have already seen the Truth distort from horizontal to diagonal to vertical. What’s left? A complete breakdown of some of the basic connections underlying our understanding. There are so many filters, the "crystal grows dark" and our ability to find meaning loses resolution. We can see as far as Pairs of Elements, but we can’t see the Elements as individual components.

The last relationship in the quad, the one most difficult to visualize, is the connection between the individual components and their grouped family dynamic. This relation indicates direction up or down through the model; Past, Present, Progress, and Future are both components and members of the Universe family. The same relationship occurs at the Element level; only it’s impossible to differentiate external from internal at that level of magnification.

Under Altruism, for example, we have the Elements Faith, Disbelief, Conscience, and Temptation. Which is more External; which more Internal? Which is more or a State or more of a Process? Individually, they seem equally comprised of aspects of External, Internal, State, and Process. For example, Faith is IN something External, but DRIVEN by an Internal commitment. It is the State of "having Faith" but also the Process of "believing."

When seen individually, an Element consists of all four External, Internal, State, and Process—which is why going down further would manifest an entirely new story. This reality is how serialized novels and episodic television works: stories within stories.

Melanie explains the specific mechanizations between the four sets of Elements in Clockwork. Comparing various Element pairings from one Class to the next, one sees the pattern involved—one closely resembling the double helix of DNA.

Next, I decided to ditch my code-system and try a bottom-up approach to see how the Dynamic Pairs of Elements changed from one Class to the next. The Dynamic Pairs of Elements were never separated which gave me some hope of finding a pattern, but their rearrangement was, again pretty random. For some reason, certain Dynamic Pairs never changed relative position at all from Class to Class (like Knowledge and Thought). I do not know what is so special about these Pairs.

Not random. Knowledge and Thought are always in the upper left-hand corner—this is the bias of the model. Look to the Co-Dynamic Pair for Knowledge and Thought within each Class and match them against their relative location in a class; once you do that, you’ll see the pattern.

Universe

Physics

Psychology

Mind

Thinking Dramatica an exercise in mental gymnastics isn’t too far from the truth. Given a specific context (Story), the Mind needs to address every relationship from every point of view before it can appreciate the meaning of the story.

The Mathematical Balance Between Logic and Emotion

A scientific theory of the mind must account for both

The quest for perfect story structure often leads one to lean heavily upon scientific method. Deduction and definitions set stable ground for those uneasy beneath the umbrella of their own subjectivity. I need to see it in order to believe it is the kind of mindset that holds many back from truly understanding that we are as much a part of what is out there as what is out there.

We are story.

And the Dramatica theory of story accounts for us within its "scientific" model.

What’s interesting to me about the Dramatica is how it connects writers to their intuition through narrative structure. While Dramatica is a theory, the logical conclusions of its concepts mean far less to me to than their ability to inspire a great work of art.

Well that concludes my rampage into Dramatica. At first I was very confused reading the Theory for the first time, then I suddenly "got it", and then I made the decision to continue digging until I am as confused as ever. Now, I am actually pretty wary of it. Nothing makes sense to me, and there is not a whole lot of information out there, which is why I am here.

This sentiment is the collective experience for every single writer who encounters Dramatica.

Even me.

The initial six months of Dramatica lift the veil from the eyes of writers deluded by other paradigms of a narrative. Suddenly, one sees the Matrix of storytelling. Then, doubt sets in. One encounters a concept or relationship that touches upon the writer's deeply-held convictions or justifications, and they project their biased preconceptions onto the model.

It can't be me; it must be Dramatica.

Most abandon Dramatica. It is better to take the blue pill and stay comfortably ignorant that writing a story is magical and reserved for a select few. They might go so far as to write a bloviated post carving their beliefs in stone in the hopes that a gathering of followers will validate their unknowing.

Still, some come to see Dramatica as a means of understanding themselves; if the theory is based on our mind's ability to hide justifications from our conscious mind, what is my mind hiding from me?

A Theory of Relationships

The Dramatica Table of Story Elements is a model of the human mind, not the mind itself. Our consciousness is not literally a bunch of boxes subdivided into fours inside other boxes divided by fours. ** Dramatica's quad theory is a theory of relationships**; the specific terms are not as important as their relationship to other terms in the model.

So how come Dramatica seems to work so well? Well, maybe it doesn't. Looking at the analysis of various movies, I am kind of struck by the leeway allocated for the categories. An MC problem of Trust, for example, could mean that MC has a hard time trusting people, MC does not trust people enough, MC does not trust himself, MC trusts himself too much, people Trust MC too much or too little, MC's relationship needs more mutual Trust, MC does not value Trust enough as an idea, MC needs to Trust his feelings or instincts or Mother's advice, or perhaps even MC wishes he had a bigger Trust fund. This one category could really be many other Elements instead, especially if each has just as much leeway.

It couldn't be "many other Elements" because shifting this Storypoint would force other Storypoints to move in relation—resulting in a less accurate Storyform. In this example, Trust as a Main Character Problem is the best appreciation of this inflection point of Conflict, given all the other inflection points.

What you describe as "leeway" is a sophisticated understanding of Trust, not a nebulous one. Every single item in the Dramatica Table of Story Elements works on a sliding scale; one can experience too much Trust, not enough Trust, and just the right amount of Trust while still adhering to the concept of Trust—

—in relation to Test.

Test is the Dynamic Pair to Trust, which is to say that Test is the polar opposite to Trust in the context of Conflict.

There exists a discernible difference between a lack of Trust and too much Testing. Sure, some may say that someone who overly Tests is Distrusting, but what is the story about? Is the Problem for the Main Character a lack of Trust? Or is that she Tests too much? Those are two different stories.

A woman suffering from a lack of Trust would self-sabotage every relationship; that inability to reconcile acceptance (love) without proof might drive her to expect the worst from everyone. This dysfunctional line of thinking would lead her to find excuses to leave what could be a loving relationship.

Another woman suffering from too much Test might be driven to unconsciously self-sabotage every relationship. Having been abandoned by her parents at a formidable age, she may test the boundaries of her mates' acceptable behavior. Better to find out they couldn't hack it now, rather than an experience that pain of abandonment later, right?

Both examples tell a story of self-sabotage—but they each explore a different kind of Problem. The first isn't about Testing too much anymore than the second is not about Trusting enough.

Keeping the Argument Consistent

With some clever wording, MC's problem could potentially be 10, or 15, or 30 other Elements besides Trust. It is not surprising then, when looking at many of the analyses, it honestly looks like some of the categories are a bit of a stretch, where I would have never assigned it (unless Dramatica pushed me to).

Dramatica pushes you to write complete stories. A complete story is nothing more than a complete argument. Telling one side of the story doesn't work in court—and it doesn't work in the grander court of Audience appeal. If you're going to argue for the efficacy of one particular approach to resolving problems, you need to make sure you show the other side. The Audience knows when you're hiding the whole story from them.

Of course, there isn't just one story, so a system of balances must be engineered to account for every possible permutation. Enter Dramatica. The comprehensive theory of story that is Dramatica helps Authors balance the arguments of their story.

Why wouldn't you want to be pushed in that direction?

And on top of that, Dramatica gets away with any blatant inconsistencies by saying that obviously that particular movie deviated from Dramatica's perfect theoretical structure. Dramatica is pretty tricky.

** Dramatica's "perfect theoretical structure" is nothing more than a simplistic and balanced model of the mind at work.** Those films or novels that "deviate" from this form find it difficult to maintain an Audience, let alone a timeless status. Take any of the Transformer movies (except Bumblebee), or many of Quentin Tarantino or Cohen brothers films, and you find deficient narrative structure—broken "minds" of story. Yet, these works continue to connect with a specific sub-segment of the population; they appeal to those comfortable with dysfunctional psychologies (and even then, these films play against expectation for a surprise).

The first Harry Potter novel, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, is beloved by billions—yet fails to convey a complete story by Dramatica's standards. Does that mean fans shouldn't adore the book to the extent that it is? Cultures value tales as many stories. There is nothing wrong with an unrealized Storymind—but if you compared Sorcerer's Stone to the final two novels of the series, and appreciated the complete story of the entire series, you would begin to understand the purpose of Dramatica theory.

I know there obviously is a concrete computer code which runs the simulations in Dramatica Pro, but that does not mean the commands are based in a concrete logical theory.

Logical and emotional. It's telling that you skipped the latter as if logic somehow reigns supreme. This oversight is the downfall for every one actively engaged in trying to decipher the scientific aspects of Dramatica through mathematics and cold-hearted deduction. For a theory to accurately model the mind's psychology, it needs to address structural and dynamic concerns: logic and emotion. While the current coded application grants preference to the former, Dramatica's theory accounts for both sides.

Because balance is a thing.

The Problem with Scientific Analysis and Narrative Theory

A theoretical model of psychology for the best of the best

As a theory of story, Dramatica tends to attract scientists and mathematicians. With its claims of connections to General Relativity and its discovery of "Quad"-ronometry, many find themselves compelled to strike down any claims of viability. Their bias proves to be their undoing: blinded by the God of Deduction they drown in endless proofs, desparately clinging to whatever certainty they can find on the way down.

This series of articles on The Science Behind Dramatica exposes the nature and problems inherent in a justification built on certainty.

I want to elaborate a bit more on the difference between a theoretical model and a model tacked on to experimental data (a practical model). A theoretical model or equation is born in this way: axioms and assumptions are listed, a series of logical steps proceed (a proof), which leads to a conclusion (our model or equation). Many mathematical and scientific conclusions are made in this manner, and they form a fundamental basis for our understanding of reality.

Dramatica is a theory of story. Mental Relativity is a theory of human psychology.ramatica is an extension of MR with an emphasis on narrative structure. Dramatica's understanding of conflict resolution within the mind is a theoretical appreciation of reality.

The above elaboration, like many scientific evaluations of Dramatica, defers to Deduction as a prime directive. Every aspect of investigation must adhere to this certainty-based principle—anything outside the realm of logical possibility is deemed false, or "wrong." This idea that a theoretical model must follow a line of thinking in service of Deduction blinds many to the equally important Induction aspect. Inference is every bit as important as cold-hearted and calculated Deductions. Without it, Deduction would carry little to no meaning—a method of thought that determines certainty encourages a level of thinking in search of potentiality.

A human psychology model must account for both problems of Deduction and Induction if it is to exhibit any level of accuracy.

The Dramatica Model of Psychology

In an attempt to capture the processes of psychology within a narrative model, Dramatica assumes the following:

- a mind, when confronted with an inequity, must resolve that imbalance

- addressing inequity is a process of problem-solving or justification

- passing on this process is an essential component of human evolution

- communicating this process requires the juxtaposition of both objective accounts and subjective experience

- the degree to which the provided perspectives are complete determines the quality and strength of the message

If you don't buy into the given that every complete story is an analogy to a single human mind resolving an inequity, then Dramatica is not for you. If you can't balance Deduction against Induction, then Dramatica is not for you.

In contrast, a practical model (as I am calling it), looks at a bunch of data points and tries to find a pattern. It tacks on an equation to represent the points given, which seems to describe it pretty well.

Mental Relativity's conceptual equation of K/T = A*D was not "tacked on" a priori. This formula describes both the process of problem-solving and justification. The manifestation of this formula preceded the development of Dramatica.

This technique is used heavily in engineering fields, because engineers solely care about results. I have a background in Chemical Engineering and some of the equations describing flow of chemicals through a pipe have over 20 variables involved. These huge equations have NO theoretical basis, but simply somehow get the right result, and are mostly the effort of trial and error.

"Simply somehow" getting it right is a Male-biased mind's approximation of Holistic logic. It's the best a mind saddled by Deduction can understand Induction. This blindness arises within the A*D side of the equation—you need to justify the results as "trial and error" because you can't logically break them down. Engineers justify through results and process because deep down, they believe there is an answer, an ending, to all their work. They "believe" in certainty. This unenlightened view will always haunt them—until they resolve that inequity with a healthy dose of real insight: the search for an answer is perpetual.

A theoretical model goes from the bottom-up, and a practical model goes from the top-down. Both are extremely useful.

Your "practical" model of story is what you find in the Heroes Journey paradigm, Save the Cat!, USC's Sequencing Method, Michael Hague's Six Steps, Robert McKee's Story, Syd Field's work, Linda Seger, Pilar Alessandro, The Nut Method, etc. etc. etc.

All of those paradigms look to pattern-match successful stories to subjective concepts of what is right and wrong. The problem with subjectivity is the same problem with opinions: everyone has one.

The creators of Dramatica looked to understand human psychology first, then reached out to validate these theoretical concepts.

Dramatica seems to be a practical model disguised as a theoretical model. It really tries to be theoretical, but the logic doesn't work out. It does not start with axioms and assumptions, or have a clear logical path to its conclusion (if it does, it has not been presented). This is where my questions are concerned. If they can be answered fully, then I may come to accept that Dramatica is actually a theory.

If your givens in life consist of Deductions as the basis for all theory, then Dramatica is not a theory from your biased point-of-view. This desire for logic is only one side of the psychological equation that is a story.

Dramatica does work because it is a practical model. It is a product of looking at a bunch of data and fitting a pattern. But practical models are not fundamental, and they are not always correct. A practical model may only work for a certain range, or for certain examples. In fact, there is really no way to accurately predict for other data points with a practical model, which is why I have a problem with Dramatica. It may work for a lot of stories, but it may not work at all for others.

Of course, Dramatica does not work for all stories—only those with an intention to argue a particular approach to resolving inequities. Stories are not something that we need to figure out; we created stories to figure ourselves out. The above is nor more a revelation than a recognition of Dramatica's initial givens.

Some data points fit the equation nicely, but without theory, you have no idea if others will.

This assumption is incorrect. The predictive model of Dramatica continues to inspire wonder, even for those familiar enough with the theory known as experts. Case in point: the storyform for Top Gun. During a recent Writers Room class (Season 3, Episode 13: An Introduction to Using Subtxt to Write Stories), Dramatica confounded me again with its innate ability to predict a writer's intuition. Top Gun is no Shawshank Redemption, to be sure, but its narrative structure is simple and solid enough to work as an example of predictive models.

Of course, you'll need a little Induction to put the pieces together.

The Predictive Qualities of Dramatica

Arriving at the storyform for Top Gun is a simple matter of identifying the source of conflict from objective and subjective points-of-view. These Storypoints, when combined with an understanding of vital narrative dynamics (whether the film ends in Triumph or Tragedy, or whether it emphasizes Problem-solving over Self-actualization) and plugged into Subtxt, lead to a Premise that reads:

::premise Abandon being reckless, and you can compete against the best of the best. ::

Sums up the message of Top Gun entirely.

This Premise leads Subtxt to predict that in the first Act, the conflict in the Objective Story Plot will center around Doing, the second Act will see Conflict shift from Learning to Obtaining. Finally, the last Act will focus on Understanding.

This understanding is, in fact, the exact structure of Top Gun.

Subtxt's predictive model is structural—conventional understandings of Acts break down into four Transits. Act One is Transit One. The traditional Act Two is both Transit Two and Transit Three (sometimes referred to as 2a and 2b). And Act Three is Transit Four.

- Transit One: Maverick's cavalier attitude while flying the opening mission almost gets hiw wingman killed, and leads him to make an embarassing first showing at Top Gun school (Doing)

- Transit Two: Mav and Iceman duel it out in a series of training exercises to learn who is the best of the best, with Maverick unintentionally leaving his teammates vulnerable to win that number one spot (Learning)

- Transit Three: Mav's continuous pushing of the envelope leads to the loss of his co-pilot and an eventual loss of the coveted Top Gun prize (Obtaining)

- Transit Four: on a rescue mission, Mav shows everyone he understands what it means to never ever leave your wingman and in doing so, grants the understanding that he is the best of the best (Understanding)

To transmute "Abandon being reckless and you can compete with the best of the best" into the exact plot-level concerns of a narrative is astounding. To suggest that this predictability is merely practical and dependent upon data is ignorant.

Perhaps seeing Subtxt's prediction of a plot from Premise is not enough—with only four items to choose from, luck must play an integral part in this relationship.

It doesn't.

Diving Down into the Depths of Subtxt

Beneath these plot-level concerns lie thematic issues—meaningful variations on their more broadly-minded plot parents. Here, too, Subtxt astounds with even greater insights into the specifics of the plot.

Act One's Transit of Doing breaks down into four Progressions:

- Fate

- Prediction

- Interdiction

- Destiny

Based on that Premise above, Subtxt ever having the pleasure of sitting down and watching Tom Cruise fly an F-14 with Kenny Loggins playing in the background--accurately predicts the film's opening Act.

In the first Progression, Cougar was in the wrong place at the wrong time (a conflict of Fate)--spooked by a Russian MiG while Maverick was off having fun. This leads to his commanding officer foretelling all kinds of mayhem that will come of having to send Mav to Top Gun school instead of Cougar (a conflict of Prediction).

In their first couple of meetings, the hot shots jockey for superiority by telling the others they're wasting their time thinking they can somehow alter their destiny to be losers (a conflict of Interdiction). And then Mav shows them all by proving what a loner he is while simultaneously claiming what he considers to be his calling as the best of the best (a conflict of Destiny).

How the heck was Subtxt able to predict that correct sequencing of events from a simple Premise?

For context, there are 64 unique Variations in the Dramatica model of story. Subtxt picked these four because those are the Progressions one must start with when arguing that Premise.

"But Top Gun came out in 1986...surely, the creators of Dramatica used the film as a basis for its model of story..." Are you kidding me? A) I don't think Chris or Melanie (the creators of Dramatica) have even seen the movie, and B) it's not like Top Gun is a cinematic masterpiece...why would they even bother? It was difficult enough discovering those 64 Variations.

Oh, and C) this magical predictive ability repeats itself across all narratives—regardless of Premise.

But then, maybe Subtxt just got lucky again, let's look at the next Act...

The Magic Continues

Instead of focusing all of our attention on just one of the Throughlines present in this complete story, let's shift our attention to the Main Character Throughline of Maverick himself.

The Main Character Throughline is the personal view of the conflict in the story and gives the Audience a firsthand look at what the central inequity of the story looks like from a first-person point-of-view (the I perspective to match against the more objective They perspective of the plot).

As with the Objective Story Throughline, the Main Character Throughline of a complete story also maintains a set of four Transits.

Transit 2--where all the "Fun and Games" of fighter pilot antics takes place--breaks down into three significant Progressions within the Main Character Throughline:

- Rationalization while Past

- Commitment to Responsibility while Past

- Obligation while Past

Incredible. You probably can't see it, but that is the exact narrative structure of the 2nd Act until the traditional Midpoint.

Again, remember that we are only looking at Mav's personal journey through this next Act. While it weaves into the Objective Story Throughline plot, these Progressions describe Mav's emotional journey from hot-shot to sad friend.

After the first training sortie, Mav buzzes the training tower. While reprimanding him for breaking two rules of engagement, his instructors rationalize keeping him on-board because of his natural talents (a personal conflict of Rationalization).

Iceman challenges Mav, calling to question the hot-shots dedication to his teammates. This lack of commitment is dangerous and will likely get them killed (calling to mind a personal conflict of Commitment). Mav ignores this warning, and in the next training sortie takes it upon himself to show his instructors that the rules don't apply to him. He loses, and his wingman "virtually" dies (a failing of personal Responsibility).

Having realized his colossal mistake, Mav promises his co-pilot Goose that he will do better. This obligation proves to be too much for Mav to handle—during the third training sortie, he pushes yet again, resulting in a catastrophic accident that kills Goose (a conflict of Obligation).

Rationalization sets up the Potential for conflict in this Transit. Commitment adds the Resistance, which then manifests the Current of Responsibility. And then finally, Obligation steps on to signal the Power of this Act, and set up the Potential for the next Transit.

Of course, this all could be a coincidence. 🙄

In Need of A Helping Hand

The deductive mind tosses and turns at night when confronted with the magic of Induction. Unable to see the forest for the trees, it screams out for someone to take their hand and guide them to the other side.

Dramatica is NOT comprehensive. And Dramatica makes up for its limitations as a practical model by being vague and general, much like a Psychic reading Tarot cards but perhaps more effective.

If you mean that Dramatica possesses psychic powers, then yes, I would agree with you. If you intend to insinuate that the theory is some con, or relies on the strength of suggestion to make its predictions, you're willfully turning a blind eye.

That sampling of Subtxt's ability above is not random luck. Those Progressions perfectly encapsulate the thematic topics of Top Gun, but they also do it an order particular to that film and that Premise. Search out any other Premise, and you'll find those same issues in a different part of the story and a completely different order.

Dramatica is the first theory of story to say that order is essential—coincidence plays little part in its sequencing of narrative events.

If this is the case, and Dramatica is not a theory, then it should stop pretending or trying to be. The Dramatica Theory book should be completely rewritten to reflect its limitations. It should dump vague, weird logic and blanket terms (such as multidimensional) that do not apply and just be real with us. (I took a few multi-dimensional calculus classes and Dramatica does not include anything concrete). Dramatica should stop being advertised as a revolutionary and fundamental theory, because it is misleading.

It's only misleading to those who assume their education to be enough. It's only vague and weird to those blinded by Deduction. As mentioned in earlier articles, this post is yet another individual justified in his Knowledge, seeking out even more Knowledge. If you took the time to dive into Dramatica, you would realize that your quest for Knowledge entrenches you deeper in your justifications. Knowledge is no Solution for a Problem of Knowledge—the only viable Solution is Thought.

And I can see you have a lot more thinking to do before you get out of this story.

Instead, Dramatica should embrace that it is mostly just a practical model that works but no one really knows why. In fact, I believe that Dramatica is probably the best practical model for story structure I have ever seen. But as a practical model, you have to use Dramatica with caution. And you certainly can get a well-structured and completely satisfying story by breaking its "rules" because there is no theoretical basis for the rules in the first place.

Well argued. We can break Dramatica's "rules" because you've decided there is no theoretical basis. Your cries for certainty shine a light on your justifications and problematic preconceptions. I'm curious, were you holding your breath at the end like a petulant child, or did you grab your ball and leave?

Judging by the lack of response in the forums after seven years, I would guess the latter.

Intuition: Trusting The Intelligence Within

Allowing inference to open oneself up to potential

A recent discussion in the Discuss Dramatica forums illuminates the unfortunate consequence of a deductive mindset. Calling into question one of Narrative First's milestone articles, Writing Complete Stories, the conversation devolves into a whirlpool of reductive--and ultimately non-productive--proof of the meaning of meaning. Complete stories are equal parts logic and intuition; one must possess a command of both to see the totality of narrative structure.

The discussion, with its plea for certainty, is reminiscent of the attempt by an "engineer" to take down the Dramatica theory of story. Theory-heads disparage intuition and premise for the sure thing proven by absolute logic. They see this statement from the original Narrative First article:

All meaning is context.

and somehow find it deficient and "self-referential" when compared to this:

Meaning comes from context.

Those comfortable with inference and their gut read both as equal--and move on with their lives knowing a little something more about themselves.

Meaning and Context

The inequity present within these two diverging views lies in the gap between the narrative Elements of Deduction and Induction. Often difficult for writers to comprehend (after all, who wants to write a story about Induction?!), the difference between these two reveals the consequence of the above discussion.

- All meaning is context

- Meaning comes from context

Both statements communicate the relationship between meaning and context. To suggest that one approach is somehow more appropriate than the other is a perfect illustration of a Problem of Deduction.

If anyone struggles with Dramatica's definitions of Deduction and Induction, observe these two statements' intent. The first operates from a basis of Induction and potential to connect meaning and context. The second relies on Deduction and certainty to secure a connection.

When working with narrative, there is nothing inherently false or wrong about one mode of thinking. Bouncing back and forth between deduction and inference is a crucial competency for those engaging with Dramatica. Without that balance, bias takes over, and the conversation stops.

The initial article, Writing Complete Stories, was meant to trigger readers through inference. Wait, what? My belief system is tricking me into thinking life carries a specific meaning? And it's worked perfectly for over a decade. In fact, the conversation on Discuss Dramatica began due to a writer struggling to resolve his worldview with the Dramatica theory of story.

The Dramatica User Group meetings operate from a bias of Deduction to find Storyform. Subtxt, and its Premise feature, finds bias with Induction as it intuits Storyform. The problem with the former approach is endless debates over evidence without a connection to a more significant meaning (refer to the recent group analysis of Little Women for an example of this in action). The problem with the latter is confirmation bias and possible projection of self onto the outcome.

The Deductive thinker accuses Mr. Induction of lazy thinking, the Inductive thinker looks back and observes someone who doesn't see the forest for the trees.

The great thing about the Dramatica theory of story is its ability to objectify problematic issues. Take, for instance, the issue of Analysis within a context of Learning:

There are Deduction and Induction pitted right across from each, with Reduction and Production making an appearance. The Deductive thinker reduces possibility in search of much-needed certainty (Reduction)—but needs pages and pages of explanation to get there (Production). The Inductive thinker sees unbridled debate ("overthinking") as a detriment to Learning and employs Reduction to get to the point and keep the conversation flowing quickly.

Regardless of what corner you currently find yourself in, you need to see the totality of the quad if you're going to find success applying Dramatica to stories.

The deductive mindset, so prevalent in these explorations of The Science Behind Dramatica, creates resistance because of its need for stable and sure ground. The potential for failure with an inductive mindset is there, to be sure--but in that unknowing lies the twin human aspects of surprise and discovery. Our greatness lies not in figuring out and defining what is there for sure, but understanding that sometimes we need to trust our instincts and take that first step into the great void.

How else are we to get to the other side?

The Confirmation Bias of Pattern Matching

A concept-first approach to understanding narrative structure

Many paradigms of story structure look at stories and identify common patterns. The Dramatica theory of story runs against the grain by looking to the psychological concept first and then looking to published works for confirmation. The resultant differential in each suggests a superiority of the latter over the former: Pattern-matching finds the same story over and over again; psychology-first sees different stories told within the same framework--the framework of the mind.

This series on The Science Behind Dramatica explains the approach of looking to the mind first and then applying it to produced works of fiction. Dramatica's concept of the Storymind--that every complete story is an analogy to a single human mind working to resolve an inequity--allows writers to see structure in stories divergent from cultural norms and tendencies. If we all possess the same composition that is a mind, wouldn't it stand to reason that we would structure our stories using the same process?

Engineer-heretic completes his imagined takedown:

Well, I question Dramatica's perfect theoretical structure. Here's what I think is the deal. Dramatica has a great idea of the Story Mind and comparing a story to how human minds learn about solving problems. Another great idea is the Grand Argument Story, where all theoretical viewpoints are considered. But that's pretty much where the theory ends (which is admittedly a nice breakthrough in its own right).

Funny that you appreciate the breakthrough, yet go on to discount the concepts that arrived at that conclusion. It's easy to get the bigger picture; anyone can do that; understanding the details takes more work.

After that step most of the quad structure, relationships, and assignment of vocab, seems to have been arranged instinctively, or by whatever method produced results.

That process was the furthest thing from instinct. It took countless hours and several years of concentrated study where Chris Huntley and Melanie Anne Phillips put their lives on hold to figure everything out. While perhaps not apparent to those glancing at the decades of support material, the truth lies in the fact that the intention was something more significant than merely pattern-matching and guessing.

Once that was established, the creators (consciously or not) backtracked to fit a theory to the aggregated data that did not really fit.

Unlike every other single paradigm of story, Dramatica was theory first, then corroboration. Joseph Cambell sampled hundreds of cultural myths to write A Hero with a Thousand Faces. Blake Snyder (of Save the Cat!) wrote one film that worked, then back-tracked to apply that same paradigm to other successful works. Chris and Melanie tried something different. They didn't look at movies and novels in the hope of finding patterns; they saw patterns in psychology, and then looked to film and books for validation.

They compared the Dramatica model to mental relativity, or Einstein's e=mc2, or psychology without ever getting too concrete.

Dramatica is Mental Relativity. That came first. The base Elements of Knowledge, Thought, Ability, and Desire correlate directly with Mass, Energy, Space, and Time—so, of course, there will be comparisons to Einstein's formula of General Relativity.

Dramatica takes it one step forward to explain why Einstein blends Space and Time into a constant.

It sounds like it is based in science, but it's really just a bunch of mumbo jumbo.

That is, of course, your professional opinion.

That is why the Dramatica Theory seems vague and confusing. That is why "Dramatica experts" are still pretty confused about it all.

As an expert in the theory, I occasionally misread individual narratives. These mistakes are always a result of me arriving at a narrative set deep in my preconceptions—they have nothing to do with the accuracy or utility of the theory. The nice thing about having an objective perspective on a narrative structure is the ability to step outside of my preconceptions and blind spots to see the hole in the story and the missing piece of my understanding.

Dramatica makes it possible for me to admit mistakes while continuing to learn and develop a greater appreciation of the stories we tell ourselves.

That's why these logical gaps exist.

Logical gaps do exist—both in Dramatica and in human psychology. Dramatica's "failings" are failings of the latter. You could say that Dramatica is more "human" than any other paradigm of narrative structure.

And you would be right.

When it comes down to it, Dramatica is pretty much an advanced story paradigm, like Hauge's 6 Stages for example, except with the pretension of thinking it is a sound, logical, fundamental theory of psychology or another science.

One's inability to grasp certain concepts does not reflect a deficiency within what is being observed—but it does signal a lack of comprehension in the observer. This entire diatribe against the efficacy of Dramatica is merely a projection of ignorance: the inequity can't possibly be you, so it must be the model. An inability to recognize one's deficiencies is a core proficiency for those who don't get the Dramatica theory of story.

Dramatica models this ignorance from within the Main Character Throughline. If you open up the Plot Sequence Report for any story, you find some instances where the Main Character projects their issues into a Domain entirely separate from their own. That's what's going on here—you're blind to your justifications as much as the Main Character is at a story's beginning.

And there's no way Hague's Six Steps model defines--or even comes close to addressing--this observable behavior of human psychology.

Dramatica is mostly based on the same principal of fitting patterns to what we see in stories, which is useful but not revolutionary or comprehensive.

Dramatica was not developed by observing patterns in films or novels or Shakespeare's plays. Dramatica bases its model of the Storymind on the theory of Mental Relativity—a theoretical concept of justification and problem-solving. Dramatica's validation against famous and grand works happened after the fact. This approach is why some films, while universally beloved (Citizen Kane and The Maltese Falcon), sometimes fall outside the model.

I'd argue that proponents of Dramatica have way too much Faith in the theory.

Is it that we have too much Faith, or do you possess too much Disbelief in the theory?

And if you still don't get that, I'd be more than happy to go over it with you all over again.