Writing a Meaningful End to Conflict

Tying the climactic moment to a premise.

Many writers know how they want to end their stories. They know who dies, and who lives. They might even realize why they want things to turn out that way and how it relates to their theme or premise. The question is: does that ending resolve the conflict in a meaningful way?

Is there a reason for that theme beyond something to talk about?

The horse-and-buggy days of narrative structure are long gone. And good riddance. The hours wasted trying to evoke some usefulness out of something like the Hegelian Dialectic are now behind us. And we’re all the better for it.

That 1800s philosophy—of which many still behold themselves to—is no match for the comprehensive model of the mind that is the Dramatica theory of story. “Synthesis” and “Anti-thesis” simply don’t cut it in a world that comprehends the difference between Male and Holistic thought.

Consider the conversation in this series between a novelist proficient in his craft and yours truly. The Hegelian approach lends one to see “the old ways vs. the new ways” as a theme, and a truism beyond them as a potential solution. Easily transposed from one story to the next (which narrative doesn’t find a meaningful “synthesis”?), this method fails to zero in on the particulars of said conflict.

The Dialectic doesn’t just miss the trees for the forest—it sees a green landscape where there isn’t a blue sky.

The Essence of a Synthesis

The Hegelian Dialectic isn’t all wicked. The thesis/anti-thesis/synthesis methodology works—if you understand the cause and effect linearity of its components.

To the Hegelian, conflict resolution arrives in the form of synthesis. Key to this solution is a relationship with the thesis and anti-thesis proposed earlier on in the narrative. If the thematic argument of a film like the James Bond thriller Skyfall is something as general as “the old ways vs. the new ways,” then a synthesis beyond the old and new would save the day.

But that doesn’t happen.

The only “synthesis” that stops super-villain Silva in Skyfall occurs when Bond stops fretting over issues of his physicality and returns to form—tolerating life-risking behavior without question. Shooting up the frozen ice that keeps him safe exemplifies this meaningful change. It’s a variation of the old vs. new argument, but it’s one that is intimately tied with what actually resolves conflict in the narrative.

It’s also specific and definitive.

I don’t see the connection between Bond no longer fretting over issues of physicality (which honestly I must’ve completely missed both times I watched the film) and the old vs. new argument.

When you're making an argument, you want to make sure you cover all the bases. Leave something out, and you leave yourself open for a ” Yeah, but” exchange with your Audience. You’ll want to craft a complete argument—unless you want to open yourself up to countless conversations about what your story means.

Covering All Your Bases

A complete argument explores life as experienced through the mind. Part of this examination involves the physical expression of conflict. Another, the internal manifestation of what is at odds in the context of thinking processes and fixed attitudes. Cover them all, and you’ve helped us understand a little more about what it means to be human.

Skyfall easily captures the process of physical conflict with its action sequences—there isn't a Bond film around that doesn't do that. However, in contrast to the super-spy pantheon, Skyfall goes the extra distance by exploring the internal side of things with its portrayal of Silva, M, and the dysfunctional relationship between all three principal characters.

Where the film slips up is in its development of the conflict in an external static state.

Recognizing the Missing Piece

It's no surprise to me that you don't remember the scenes where Bond contends with his deteriorated state—what we refer to in Dramatica as a Universe problem. Skyfall efficiently manages conflict in an external process context (Physics), but stumbles with the regard of the external state—namely, Bond's aging out of the spy business.

While the film starts out strong exploring this part of the argument with Bond’s inability to shoot straight, his difficulty with the physical exams, and his consternation over holding on to the elevator, it loses sight of this potential through much of Act 2—only to bring it up for a brief moment again in the final Act when he is out on the frozen lake.

Your inability to recall those scenes and make the connection with the "old vs. new" argument is proof positive that this kind of work is necessary. As a novelist, this is your life's work, and even you can't make that connection—because it was never successfully made for you in the first place.

Bond's physicality is vital to the argument because we need to see how "old vs. new" work out under the context of a fixed external state. We require that exploration of Universe.

The Reason for Four

Context is meaning—but a context is meaningless without an understanding of the totality of meaning. I means nothing without You. They pointless unless juxtaposed We. The fixed mindset domain of Mind is inconsequential unless paired with a stationary external state of the Universe.

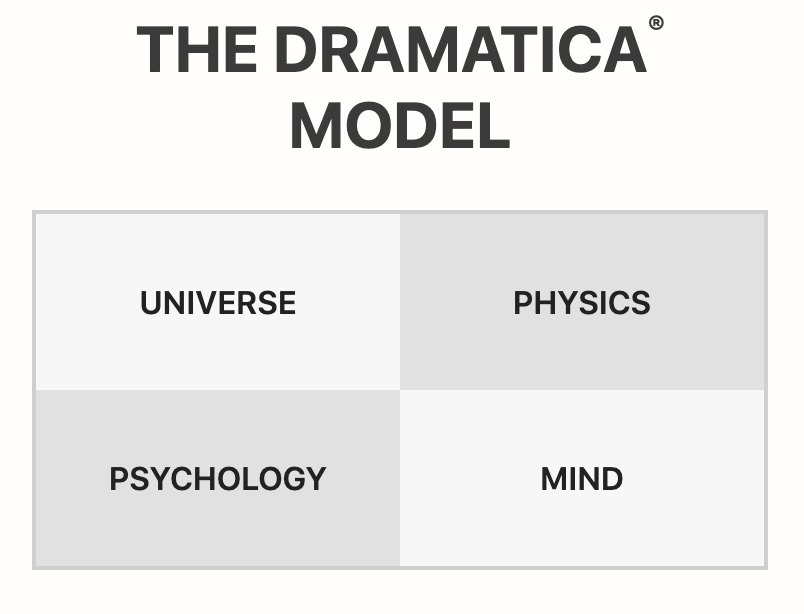

The Dramatica theory of story is based on the quad. Its appreciations of narrative structure are meaningless unless all four items of a quad appear within a single context. Physics, Mind, and Psychology are pointless without the Universe to balance them out.

A story is one such single context.

Incomplete Arguments

Do you really see this movie as exploring what happens when a secret agent begins to fret over issues of physicality?

I see an attempt to make an argument about the old ways of doing spy work versus the realities of the modern age. I know that argument half-baked and deficient as it fails to encode the Main Character Throughline context of Universe completely.

Writers intuition naturally led the Authors of this film to include this in the story—but without something like Dramatica to keep them focused, the creators of Skyfall wrote an incomplete argument.

We all have minds. And they all work the same—more or less. We see external and internal, understand state and process, and recognize binary and analog. The Authors of the film intuitively sensed the need to address the fixed external state of things and wrote in his struggle with "getting older"—they just dropped it for much of the traditional second Act, making the final argument less convincing than it could have been.

A Meaningful End to Conflict

At the beginning of the film, a Deviation and intolerable shot sends Bond to his “death” with a drowning. In the end, he comes back to life by drowning himself at Skyfall’s frozen lake. That is behavior only M would have tolerated in the past—behavior Bond has now “synthesized” into his own repertoire.

His Resolve now Changed, Bond can get to the task of taking down Silva and resolve the rogue agent’s intolerable behavior (more evidence of a Deviation problem). Blowing up MI-6 and releasing names of secret agents is unacceptable, but ultimately unavoidable in a world where you can’t tell friend from foe—unless you meet them on the ground and face-to-face.

M was right—and is proven right by the film’s events—in her support of Bond. Her Steadfastness brought down Silva just as much as Bond’s Changed Resolve secured the future of MI-6.

An Objective Appreciation of the Author/Audience Contract

With Dramatica, you have something as simple and concrete as the appreciation of Main Character Resolve—was that Resolve Changed or did it remain Steadfast?

In Skyfall, Bond resolves to not take things so personally in the future. His Resolve is Changed. Put him on that same train in the next film, take the same shot—and he’s not going to disappear off the grid. He would most likely respond with, ” Well, I would have done the same,” because he would have—after his experiences in Skyfall.

It’s interesting because, while maybe this is true,

It is. 😂

I really never noticed it in the film in any significant way. To me it’s as if a smaller, almost trivial aspect of the story is being raised up as the most important while the things that drive me to watch the next scene disappear when looking back at the storyform. You know what I mean? I see a scene in which Silva tells Bond he’s an idiot for trying to still be one of these old-school queen-and-country spies in a new world, and I want to see if he’s going to be proven right. I don’t really care whether Bond is going to think, “Right then, I guess I really am expendable and that’s okay."

That's because when you write your novels, you're 100% locked into the subjective point-of-view of your characters. There's nothing wrong with that—it's obviously worked out quite well for you. And the popularity and success of your work are proof enough that to be a great writer you don't need to understand your work objectively.

If, however, you want to step outside of yourself for a moment, the Dramatica theory of story is your friend.

A Companion while Writing

For you, it looks as if this relationship between Author and objective theory would work best during a rewrite—singularly if you're not inspired enough by what Dramatica offers to include it in your first draft.

Note that not all Authors are like this. Dramatica is not merely a “tool for analysis,” as many would have you believe. I know several working professionals who, under extreme deadlines, prefer working the narrative structure of their stories out if not a priori, then in tandem as they write.

Dramatica and my practical application of the theory Subtxt is key to their productivity.

With or without these tools, the end result is always the same: a meaningful story with something to say. The question is—when do you want to jump on the carousel of writing and rewriting?

With the Hegelian Dialectic, you never know when to get on or off—worse, you don’t even realize the carousel exists. You end up spinning around in circles with no end in sight.

With Dramatica, writers now possess an awareness of how they think—which makes it even easier to get those intentions out and into the form of a great story.

Download the FREE e-book Never Trust a Hero

Don't miss out on the latest in narrative theory and storytelling with artificial intelligence. Subscribe to the Narrative First newsletter below and receive a link to download the 20-page e-book, Never Trust a Hero.