The Hegelian Chronicles

Learning to write your story

The romanticism of ancient philosophy often leads many a writer astray. The assumption of accuracy in centuries-old concepts blinds one to present realities and modern understandings of consciousness. Do we still adhere to Ptolemy’s Earth-centered Universe? Of course, not. And neither should we cling to the reductive nature of the Hegelian Dialectic.

The Curse of the Hegelian Dialectic

The rational alone is unreal.

Thesis. Antithesis. Synthesis.

Mention these three words together, and you unlock the accursed genie that is the Hegelian Dialectic. Rising from the mystic ashes of ancient philosophy, the Hegelian promises riches beyond comprehension for those who follow his three-step process towards resolving conflict.

You only have to turn a blind eye to how the other half lives.

Hegelian Dialectic--which, interestingly enough, didn't even come from Hegel himself--is a Male Mental Sex process of solving problems.

A truth, or problem, is introduced. An alternate truth, or Antithesis, enters the scene to maximize conflict. And then the resulting solution, or Synthesis, finds a third truth that takes the best of both to resolve the original problem.

Classic Male Mental Sex, cause and effect problem-solving.

But then, what on Earth is Mental Sex?

A Unique Understanding of Narrative Structure

While an entire book could be written about the concept itself, Mental Sex is the idea that our minds run on one of two distinct operating systems.

One prefers space over time, and problem-solves through cause and effect (if that, then this). The other prefers time to space, and justifies inequities through managing relationships (you are another me).

In Dramatica theory, the mind that filters through cause-and-effect is defined as having a Male Mental Sex. The mind that filters through relating inequities is defined as having a Female Mental Sex.

Some versions of Dramatica theory equated Male Mental Sex with Linear thought, and Female Mental Sex with Holistic thought. The problem with this equivalence is that both Male and Female Mental Sexed minds can think consciously in terms of Linear or Holistic thought. Earlier versions of this article and others fostered this misinterpretation with its attempt to conceal this enlightening concept behind the more acceptable notions of Linear and Holistic thought.

Mental Sex is not the same thing—which is why throughout Narrative First and Subtxt you’ll find this original concept restored to its rightful place in the discussion of narrative structure.

::advanced It’s important to understand that Mental Sex is NOT determinant upon Gender, nor does it correlate with Gender Preference and/or Gender Orientation. Mental Sex defines the boot record base-operating system of the mind, and nothing more. ::

Back to the Hegelian Dialectic and it’s roots in Male Mental Sexed appreciations of narrative structure.

The Female Mental Sexed mind takes a different approach. Seeing inequities instead of problems, and equities instead of solutions, the Female Mental Sexed mind deals in the consistent application of balance.

Watch then, as the vaulted genie-us and supremacy of the Hegelian dissipates into the ether.

The Method of Balance

My series on The Female Mental Sex Premise addresses that train of thought wherein the wheels never stop turning. The Male Mental Sexed mind believes in the Solution--the resolution that permits one to move on, knowing the problem to be "solved." The Female Mental Sexed mind realizes problems themselves are manufactured within the mind and that nothing is ever solved, it's only balanced for the time being.

I read your article about holistic premises and watched your writer's room session, and it made me think about the Hegellian notion of the Dialectic and whether that might apply to Dramatica from the holistic standpoint – that we have thesis (problem), antithesis (solution), and that what you're calling balance (which to me sort of implies just sticking them on a linear scale and going halfway between) might be thought of as synthesis – finding a way to forge a new perspective from the two?

This would be a Male Mental Sexed interpretation of balance—that there is a scale that exists between the two and once the perfect balance point is found (a synthesis), then all potential is resolved, and a solution has been found.

Hegelian and his followers were die-hard Male Mental Sex thinkers.

The Female Mental Sexed mind knows there is never a real synthesis, but rather a constant cycle of growth and rebirth, continuous attention applied to balancing out inequities that are never truly solved.

I'd argue that they are solved but that every new balance (the synthesis that becomes the next thesis) creates the necessary preconditions for its own antithesis.

The Male Mental Sexed mind needs to argue that problems are solved because it can't function without the recognition of problem and solution.

This is, in part, where "mansplaining" comes from: the Male-minded person interrupts the Female Mental Sexed mind because it believes that what that other mind observes is somehow inaccurate or insufficient, when what they're seeing is, in fact, what they're actually seeing.

The Male Mental Sexed mind sees problems that are solved; Female Mental Sex sees inequities that are met with equities. Neither is more right than the other, but indicative of a baseline for appreciating conflict.

The structure of a story must know the baseline of the mind of the story because it affects the order of concerns in a narrative. If you see everything as a problem that needs to be fixed, you're going to go about solving that in a completely different way than someone who registers everything as an imbalance requiring balance.

The Hegelian Explained

I hear you about the scale being a Male interpretation of balance. However you wouldn't think of a Hegellian synthesis as being finding a point on that scale.

And neither would the Female Mental Sexed mind in the process of resolving an inequity--as that point on the scale doesn't exist for the mind that thinks that way. There are no points to the Female Mental Sexed account of experience, only waves.

A classic example is the notion of early childhood, where doing everything your parents say is the necessary normal state (the thesis = obedience). You become a teenager and begin to resent the oppressive nature of parental control and so rebel against everything they say (antithesis = rebellion). It's only in becoming an when you reconcile the two oppositions – not through balancing "some" passive acceptance with "some" automatic rebellion, but through the realization that you require true independence which neither involves obedience nor rebellion (synthesis = independence).

So rebellion is the linear response to control, but independence is the synthesis that emerges from the clash of those two forces.

A synthesis is still a Male Mental Sexed approach to solving a conflict. Both perspectives are evaluated separately for rightness—if one is right, or more right, than the other than that perspective is the solution. If neither is correct, then balance is the solution. If balance doesn't work, then neither can exist.

Every thought process is an if...then statement—a primary function found in any programming language (even the most basic of programming language, BASIC).

It's neither the Male Dramatica move from one to the other nor finding a balance point on that scale, but rather the solution which removes the existence of the conflict (and in doing so, introduces a new thesis which will one day meet its antithesis as the cycles of growth and conflict continue – as you state below.)

Male Mental Sex in Dramatica theory refers to the process that sees conflict as a problem to be solved. Moving from Problem to Solution is Male. Finding a balance point on a scale is Male. Finding a Solution that removes the existence of conflict is Male.

The Female Mental Sexed mind can never remove the existence of conflict because inequity always exists. It's merely a matter of how much or how little.

The Matrix, which is structured with a Female Mental Sexed approach to conflict, doesn't serve up an account of synthesis—Neo hasn't become one with his awareness and self-knowing. But he has become composed with the overall balance between the two and can literally shape his world accordingly.

I always thought what was going on with the Matrix was:

Thesis: We are waiting for "The One" Antithesis: Neo isn't actually "The One" (when he meets the nice old lady in her house or whatever and she says he's not the one) Synthesis: Neo wasn't The One until he became The One.

So both thesis and antithesis were wrong until Neo changed and made both of them true.

Another way to look at the narrative conflict within The Matrix, one that is closer to the foundational structure of the film, is to see it as a juggling back and forth between Awareness and Self-awareness.

The Oracle wasn't wrong. She was only confirming what Neo already was already aware of. And Morpheus wasn't wrong either. His identity with self-awareness above all else was also right. Both positions are self-evident as appropriate throughout the film. And we experience the movie as a mind that seeks balance in all and sees all would when facing a similar inequity.

My previous article The Female Mental Sex Experience of Watching The Matrix shares an account of what it feels like when you take everything in at once. No judgments. No evaluations. No problems and no solutions. Only the flow of allowing one position in after the other and then back again.

A Matter of Intention

You know that feeling of frustration you sometimes get when someone close to you won't just do what they should to solve the problems in their lives?

That's often someone comfortable with a Female Mental Sex approach--a method of “problem-solving” that doesn't recognize the problem, nor the potential solution.

The "solution" for the story inequity is about synthesizing the two opposing forces into a new perspective rather than either picking one or the other or merely compromising between them.

The balance of inequities for the Female Mental Sexed mind is also not a compromise. Female Mental Sex does not compromise. They don't give this for that, and any suggestion that services rendered are an exchange for goods offends as it suggests some obligation supplants the growth of the relationship.

The Female Mental Sex mind is never at ease with forcing two into one, only at ease with a shift in direction that increases the flow of communication.

To the Female Mental Sex mind, there is no real Solution that solves it all—only an Intention. Neo isn’t completely self-aware at the end, he only has the notion that there is something more than what he sees with his eyes—and he’s going to show everyone else his world.

This Intention to balance out his awareness with a personal truth sets the mind in a different direction—opening it up to receive whatever various sort of inequities that suggest an alternate path.

In a Changed Resolve/Female Mental Sex Minded story, the Main Character intends to balance out the inequity of their Throughline with an equitable element. That's why in future versions of the theory, you're likely to see Problem and Solution within Female Mental Sex stories adjusted to reflect their real purpose: Inequity and Intention.

The Dramatica theory of story is a holistic appreciation of narrative structure--which is to say that the relationship between Storypoints is as equally important as the structural concerns themselves. The theory develops in the way that all dynamic relationships do, by shifting back and forth, appreciating the lack of a specific solution.

Like the genie who emerged to grant untold fortune, the writer tied to the Hegelian Dialectic is trapped--trapped in the bottle of cause and effect and Male methods of problem-solving, unable to see the totality of the world around them. Rich, but rich with an even higher cost. Whereas those swayed by the Siren Song of a centuries-old philosophy shackle themselves to ancient knowledge as if truth, the writer familiar with Dramatica appreciates the need for further thought, and if needed--a change in direction.

The Seductive Nature of Synthesis and Subject Matter

When a problem isn't a problem.

Synthesis sounds good. It reminds us that we're better together, that 1+1=3, and that a win-win situation is always better than a no-win situation. Reaching a synthesis draws us in because it feels like the very best way to resolve conflict.

Problem is-- it's not the only way.

As demonstrated in the previous article, The Curse of the Hegelian Dialectic, the Male Mental Sex approach to resolving conflict fails to capture the totality of everyone's experience. The Hegelian Dialectic concept of thesis-antithesis-synthesis works--but only if one accepts the presence of a problem and a solution, and a cause and effect process for dealing with those problems.

The Cause and Effect of Synthesis

A Female Mental Sex mind understands problem and solution and can appreciate cause and effect--but its baseline of operation runs on tides and waves, allowance and direction. It sees inequity where one sees a problem and equity where another sees a solution.

Thesis-anti-thesis-synthesis appears in a Male mindset and context:

In the obedience example [from the previous article]. . .

Thesis: children must be obedient to their parents for their own good

Anti-Thesis: ongoing Obedience is oppressive

These two are fundamentally incompatible notions and thus clash until . . .

Synthesis: We stop being children and thus no longer require the Obedience.

This example of Obedience is cause and effect reasoning. Both thesis and anti-thesis cause problems: if we continue to allow them to persist, then the effect will be higher and greater conflict. Therefore, the answer (solution) is to stop being children, and we will no longer require Obedience.

The Compromise of a Solution

The Female Mental Sex mind is never at ease with forcing two into one, only at ease with a shift in direction that increases the flow of communication.

I agree – synthesis isn't forcing two into one. It's not, "fine, let's have hot dogs and pizza". It's more like, "it's time we stopped having dinner together" or "both our choices are actually bad for us, so it's time we started eating salads"

The result is still a solution.

By forcing two into one, I refer to the Male Mental Sex concept that a third truth somehow solves two opposing truths. To the Female Mental Sex mind, no solution ever works because those truths still exist. They can never be proven wrong because, remember, the Female Mental Sex mind sees the totality of everything all at once. In that snapshot appreciation of duality, all points-of-view maintain their truthiness--throughout the narrative, from beginning to end. Therefore, all one can do is balance the flow of those truths.

There is no solution.

The Matrix is a perfect example of the Female Mental Sex approach to resolving inequity. Personal truths are held up against natural skepticism from beginning to end, with no solution that saves the day. Only an intention. A beginning to believe.

Again, this is different from the interpretation I always took from the Matrix, but I'm open to the possibility that I just never really understood the movie properly. I will say that seems a little out of step with the movie itself, which is so often positing pretty strong philosophical perspectives about reality vs non-reality.

There is a difference between what characters talk about and what is driving narrative conflict.

There is a difference between Theme and Subject Matter.

Subject Matter and Narrative Structure

As characters within a story, we could be talking about the indignities of border control and internment camps. But what drives our conversation is an argument between certainty and potentiality. I'm confident that illegal immigrants lead to higher instances of crime, while you see the potential of hostile hospitality to create even greater evil.

Many would assume Safety or Compassion to be the Theme of such a conflict, but they're not. Safety and Compassion are simply the topics of Thematic consideration. It's what you want to say about Safety or Compassion that determines Theme.

When discussing these topics, we could just be arguing about certainty or potentiality. Or we could be exploring the difference between cause and effect. I want to stamp out the roots of terrorism, while you focus on the impact of people fleeing third-world countries. Or we could even be arguing a motivation door logic vs. a motivation for feeling. If we let everyone in, then we're vulnerable--versus the strength of vulnerability that comes from caring for everyone.

Regardless of the specifics, those Elements drive the narrative and determine the order of thematic concerns within a story. Certainty and Potentially are Theme. Safety and Compassion are Subject Matter.

The characters in The Matrix spend an excessive amount of time talking about reality vs. non-reality, but what are the Authors saying about those conversations?

That's where you'll find the necessary information to structure a story.

Are the Authors saying what you're seeing can never fully align with the objective reality of things? Or are they saying perception and reality are simply a matter of juggling your disbelief with a little faith?

Are they arguing that you need to begin to believe?

Know Your Intent

Both synthesis and subject matter play into the development of a dramatic argument. The former requires Authors to dig deep into their creative intentions and unearth the real purpose of their writing. Is it to explore this area of human experience, or is there something you want to say about this particular part of life?

With the latter, writers must question the appropriateness of synthesis given the context of their work. Are you drafting a process that sees problems in need of a solution? Or are you writing about the experience of addressing inequities in our lives?

If you answered yes to the last question, know there is a way to structure your story that honors that intent. One that doesn't force you to undertake the linear process of reaching a synthesis.

You don't need to compromise your understanding of the world.

The Illusion of Fixing Problems

Moonshots require something more than synthetic solutions.

A Male Mental Sexed mind finds solutions to problems. It develops hydro-electric power, discovers a cure for polio, and finds a safer spot to land the Apollo 11 Lunar Module. Our human experience requires solutions to problems if we are to endure for the next thousand years.

But our survival also relies on the understanding that problems are simply made up in the mind. They're not any more real than our most fantastic dreams. What we perceive as problems are simple imbalances or inequities. We label them a problem when we think they can be fixed.

Sometimes that imbalance, or inequity, is just what it is--an imbalance--and no amount of solving will ever absolve us of its impact.

We need solutions to survive.

We need an appreciation of inequities to thrive.

Appreciating the Female Mental Sexed Mind

This series on The Hegelian Chronicles examines the long-term impact of the Hegelian Dialectic on narrative structure. The myopic stance incurred by this centuries-old philosophy leads many astray. Writers inherently drawn to more holistic thought must force-fit their understanding of the world into one much more Male Mental Sexed in nature.

The Female Mental Sexed mind knows there is another way to approach holism that isn't merely an appreciation of holism through "synthesis."

What's an appreciation of holistic [thinking] vs. an approach of holistic [thinking]?

The Hegelian might think, or appreciate, their synthesis holistic in nature—but their approach is always decidedly logical.

To the Male Mental Sexed mind, Female Mental Sex "problem-solving" is not even a real thing. It sounds like excuses or laziness or nonsense because it's not addressing the problem directly. It's justifying away a problem, rather than addressing it directly. The Female Mental Sex approach is easily discounted because it's literally not logical.

In the Dramatica theory of story, this disregard of experience finds evidence in the Audience Appreciation of Reach:

- Female audience members empathize with both Male and Female Mental Sex

- Male thinkers can only sympathize with Female Mental Sex

This is the source of the dismissive phrase "chick-flick." Male Mental Sexed minds avoid these kinds of stories because the characters within them don't think as they do. They don't make any sense.

The Mental Sex appreciation of narrative structure (Male or Female) is a blind spot for Male thinkers. This lack of self-awareness explains why you'll find most of them advocating the Hegelian Dialectic approach to synthesis. It's an approach that makes sense to them and appears to be holistic in nature.

Its solution may be holistic, but the way it was arrived at is not.

This is why the Dramatica theory of story stands out from every other appreciation of narrative structure. Dramatica is a theory of how the mind works, not a formula or form for conflict resolution.

The Female Mental Sex Approach

Appreciating this difference in resolving inequities requires an understanding of the difference between the Female Mental Sex approach and a holistic approach.

To a linear thinker on the Allied side, WWII was a conflict between good (Allies) and evil (Axis). To the Axis it was a conflict between systemic oppression (people keep forcing us down, preventing us from achieving our own greatness) and self-determination (we are justified in doing whatever it takes to achieve our destiny).

WWII was the linear clash of those two perspectives. Neville Chamberlain's policy of appeasement wasn't a holistic approach. It was still based on the notion that those two perspectives existed on a linear scale. The holistic approach was the Marshall Plan (we'll keep having the same war over and over unless we actually financially step up to ensure Germany and Japan are viable states).

The Marshall Plan, while holistic in nature, was the result of Male Mental Sexed cause-and-effect reasoning. The effect of Chamberlain's policy compels us to find a different approach that won't cause that to happen again. The Marshall Plan was a solution to the problem of Chamberlain's policy.

The solution was holistic. The method, or approach, to that solution, was Male.

Contrast this with Japan's approach to conflict during the same period. The Male Mental Sexed mind would have you believe that the reasons for the attack on Pearl Harbor were limited resources and a strike-first policy. This assumes that the people of Japan were driven by a cause and effect methodology.

They weren't.

In fact, the culture in Japan at that time was predominantly Female Mental Sexed in nature. Siding with Germany, manipulating sentiment against the Chinese, and yes, attacking Pearl Harbor were all the actions of a people who only saw inequities—not problems. Their efforts were intentions of balance (or imbalance), not solutions of conquest.

An Intention of Equity

There is no solution at the root level of the Female Mental Sex mind because there is no such thing as a problem—only inequities that are met with equities (Intentions). Sample any of the Female Mental Sexed narrative structures on Subtxt, and you'll find a collection of films and novels that emphasize self-actualization over reaching goals.

For the self to thrive, one must appreciate the inequity for what it is: something that can't be fixed. The balancing of the inequity isn't a solution, it's a shift in direction that opens us up to even higher intentions.

Seen holistically, the synthesis examples of Obedience and WWII are only temporary fixes. Their solutions are fleeting because those inequities always exist, waiting to rise back up to the surface.

Thriving while Surviving

When the Apollo 11 Lunar Module left the Moon behind, it first needed to dock with the Command Module orbiting high above. This was a problem that needed a solution. Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong could not return home safely without cause-and-effect Male Mental Sexed thinking and precise calculations.

They succeeded. Miraculously, this tiny two-person vehicle rendezvoused with another spacecraft 239,000 miles away from planet Earth.

Right before they flipped the switch to ignite the rocket on the Moon, tensions were high. No one knew for sure whether their calculations were correct, or if the Eagle Lander would simply explode on the surface.

Houston gave the go-ahead signal and waited.

Buzz responded, "Roger Houston, we're number one on the runway."

A response of jocular equity seeking to level out the inequity of unpredictability. A little humor to dispel the tension, moments before they began their miraculous return back to Earth.

With Male Mental Sexed observations, we survive. With Female Mental Sexed appreciations, we thrive.

With both, we triumph over the impossible and transform the way we live our lives.

A Synthesis in Search of a Solution

Presuming conflict to be a problem.

Finding a solution to a problem assumes the presence of a problem. While this approach works great for Moonshots and the building of bridges, its reliance on cause-and-effect reasoning blinds one to a reality bereft of problems. The assumption of problems in the presence of conflict forces the search for a solution that may never present itself.

This series of articles entitled The Hegelian Chronicles seeks to explain the mechanism of thought behind the much-vaunted approach to story structure that is the Hegelian Dialectic. Seeing this simplified process of conflict through the eyes of the Dramatica theory of story makes evident the deficiencies present with the Hegelian methodology.

It’s interesting because it means the Dramatica model doesn’t really account for a dialectical notion of conflict in thesis/anti-thesis/synthesis but either finds a linear choice between thesis and anti-thesis (problem -> solution) or simply failure of the story goal, with the alternative being answering inequity with intentions.

Within the context of the Dramatica theory of story, the thesis is not the problem, and anti-thesis is not the solution. Instead, the process of thesis/anti-thesis/synthesis is a Male-minded approach to conflict resolution. This Illusion of Fixing Problems unthinkingly marks “synthesis” as its solution.

Dramatica accounts for the dialectical notion of conflict with its appreciation of the Male mind’s problem-solving process. The theory moves beyond this initial understanding by recognizing the Holistic's preference for inequity resolution over problem-solving This dynamic of narrative—a Male or Holistic approach to resolving conflict—determines the structure and order of events in a story.

The Hegelian Dialectic is a logical approach towards conflict resolution through cause and effect. Stories written with this approach in mind always set the Problem-solving Style of the narrative to Male.

Logic is literally in the DNA of the Hegelian Dialectic.

The problem is that this approach always thinks there is a problem in need of a solution.

The Holistic understands otherwise.

Living the Hegelian Lifestyle

With the Hegelian Dialectic, there is a problem (thesis), something that contradicts or negates that problem (anti-thesis), and a solution (synthesis) that results from the conflict between the two. However, the process itself is wildly open to interpretation--Hegel himself didn't even use the formula attributed to him. Instead of problem and solution, think of thesis and anti-thesis as placeholders for the Main Character and Obstacle Character perspectives.

The Main Character maintains a perspective (Thesis) and the Obstacle Character counters with the “negation” of that perspective (Anti-thesis). One gives way to the other and loses the unnecessary, or non-essential, components of the Thesis. The remainder mixes with all the good of the Anti-thesis. The product of this interaction then "resolves" the conflict under the banner of Synthesis.

The process appears holistic in that it accounts for all sides. After all, it ends in a holistic "synthesis." This outcome is mere Subject Matter--the topic of the Hegelian process, not the process itself.

The Process of Conflict Resolution

When Dramatica speaks of Male or Holistic, it is specifically referring to the process the mind employs when it meets an inequity. One, fueled by serotonin, proceeds in a sequence of steps in search of a solution. The other, guided by dopamine, adjusts the relative impact of concerns in allowance of an outcome.

The label “Problem-solving Style” is a bit of a misnomer, as the Holistic mind operates outside of problems and solution. The original terminology for this concept was Mental Sex: Male or Female. Far more accurate in its assignation of the central operating system of the mind, Mental Sex determines the order of concerns when we process conflict.

A Male, or Male, mind operates in steps. Thesis. Anti-thesis. Synthesis. One, Two, Three. Problem and Solution.

A Holistic, or Female, mind seeks balance first. Inequities and Intentions. Numbers. Imbalance and Allowance.

Hegel, Kant, Fichte, etc. advocate their three-step process as a means of prescribing a logical method for overcoming conflict. A series of steps in search of a solution. The Male-mind overcomes inequity; the Holistic-mind manages it.

Keeping the good parts of the thesis while overcoming its limitations through the anti-thesis is a step-by-step process of contradiction. It presupposes a linear progression from the less sophisticated thesis to the more evolved synthesis.

But it’s still Male.

Storyform and Subject Matter

That does a lot to explain why so many of my own books don’t fit comfortably into a Dramatica storyform – the final equation of those books is often success but neither through shifting between the available Dramatica opposition elements (e.g. faith vs. disbelief, proven vs. presumption . . . etc) nor as what you describe as a holistic approach.

The Dramatica storyform offers a series of Storypoints that connect you the Author directly with your Audience. It’s where both writer and reader observe the same thing from two different points-of-view.

The Veil Between Author and Audience is the storyform—tiny holes in the black construction paper of communication where the message shines through.

In other words, if you’re an Author and you have an Audience—you’re going to have a Dramatica storyform. The question is: How well-formed is it?

The “final equation” of your books is Subject Matter, i.e., what you’re talking about in terms of a solution--not the specific method or Element that brought about that solution.

Take, for instance, your earlier example of maturation and Obedience:

A classic example is the notion of early childhood, where doing everything your parents say is the necessary normal state (the thesis = Obedience). You become a teenager and begin to resent the oppressive nature of parental control and so rebel against everything they say (anti-thesis = rebellion). It’s only in becoming an when you reconcile the two oppositions – not through balancing “some” passive acceptance with “some” automatic rebellion, but through the realization that you require true independence which neither involves Obedience nor rebellion (synthesis = independence).

Obedience to Rebellion to Independence.

One thing we know for sure, right off the bat with this example, is that it illustrates a Male-minded Problem-solving Style story. Not just in the sequencing, but in terms of responses to inequity as well. If this doesn’t work, then this will. When that doesn’t work, later I’ll try this. If I want peace, then I need to recognize I need independence. Once I do that, I resolve my problems from childhood.

Classic thesis-antithesis-synthesis thinking: Problem to Solution. Cause and Effect. Logic.

If Dramatica is a model of the mind’s problem-solving process, then where would we find Obedience within that model? Or Rebellion or Independence?

We wouldn’t.

One mind’s version of Obedience is another’s source of Independence. Those topics describe sources of Subject Matter, not conflict. Context is everything--which is why we developed the need for Throughlines in our storytelling. Assigning perspectives to the source of conflict gives us the grounding we need to understand the context of what we are looking at within a narrative.

To some, Obedience is a solution. To others, it’s a problem. And to many others, often not represented in discussions of narrative structure, Obedience is merely an issue to be addressed—not solved.

Setting the context of your story grants the Audience insight into your particular point-of-view.

Perspective and Conflict

There is no meaning without context.

No meaning exists without knowing what kind of Obedience, or what type of Obedience you seek to explore.

No meaning persists without knowing what specific issue and core motivation drive that particular instance of Obedience.

You need to give your Audience that one single mind to inhabit--the Storymind that is your story. If not, your readers will misinterpret your intentions by shifting the context to suit their individual needs.

Instead of synthesis, seek out context. Instead of thesis and anti-thesis, unearth the source of conflict in your narrative.

But above all, understand the operating system of your story’s mind.

Is your story solving problems in a Male Male cause-and-effect manner? Is it working in steps from Thesis to Anti-thesis to Synthesis?

Or is Synthesis there from the beginning? Is it possible that the story isn’t seeking a solution to resolve conflict because it doesn’t even recognize the presence of a “problem”?

Consider a film like The Farewell from Lulu Wang. Is there a solution needed to fix Billie's problems, a synthesis that solves thesis or anti-thesis? Or is the story more about what personal sacrifices are worth addressing in allowance of an outcome?

Is it really about finding the balance to meet the imbalance of life?

Perhaps, the only real problem is the assumption that conflict is something that needs a solution.

Perhaps the real problem is applying a centuries-old philosophy to a complex process that requires a more modern understanding of narrative dynamics.

Perhaps it’s time to emerge from the cave and shed the limiting blinders of the Hegelian Dialectic.

Skyfall: Finding the Synthesis in Dramatica

A modern understanding of conflict resolution.

When it comes to the structure of a functioning narrative, it should come as no surprise that we know more today than we did in the 1800s. Yes, photography and the steam engine were once modern miracles, but that was then. Today—and much to the chagrin of steampunks everywhere—we don’t continue to uphold the days of old.

Today, we possess supercomputers in our pockets that access the world’s store of knowledge, measuring their speed in milliseconds.

Why on Earth then, do we continue to hold up ancient philosophies like the Hegelian Dialectic as if its age somehow makes up for its gross inaccuracies?

Moving Past the Past

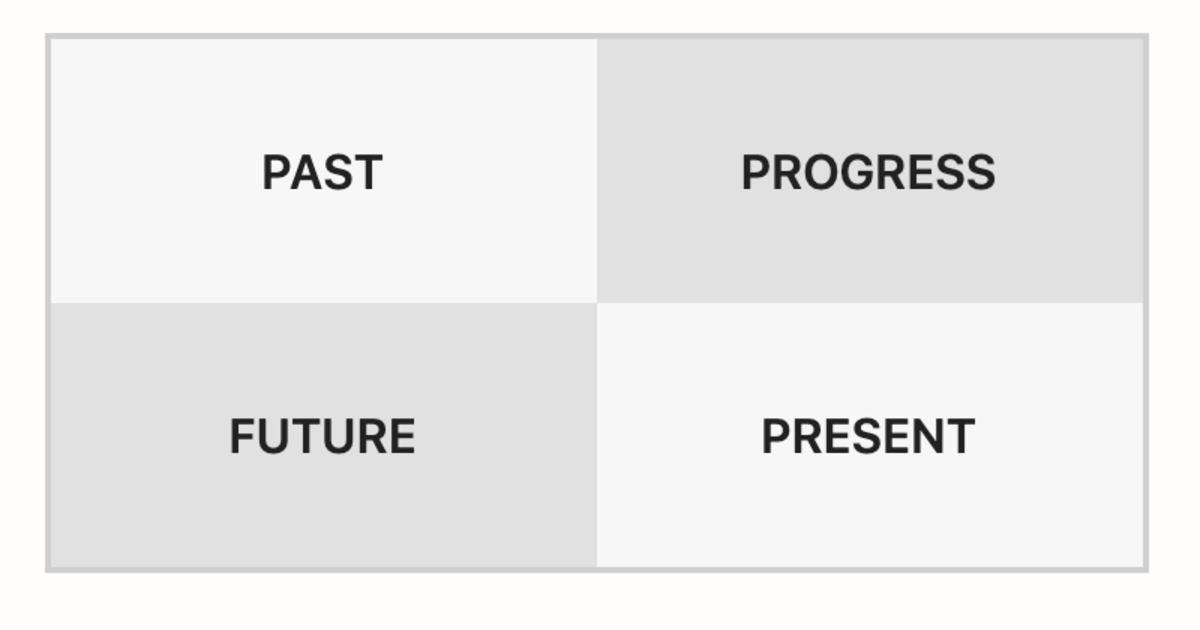

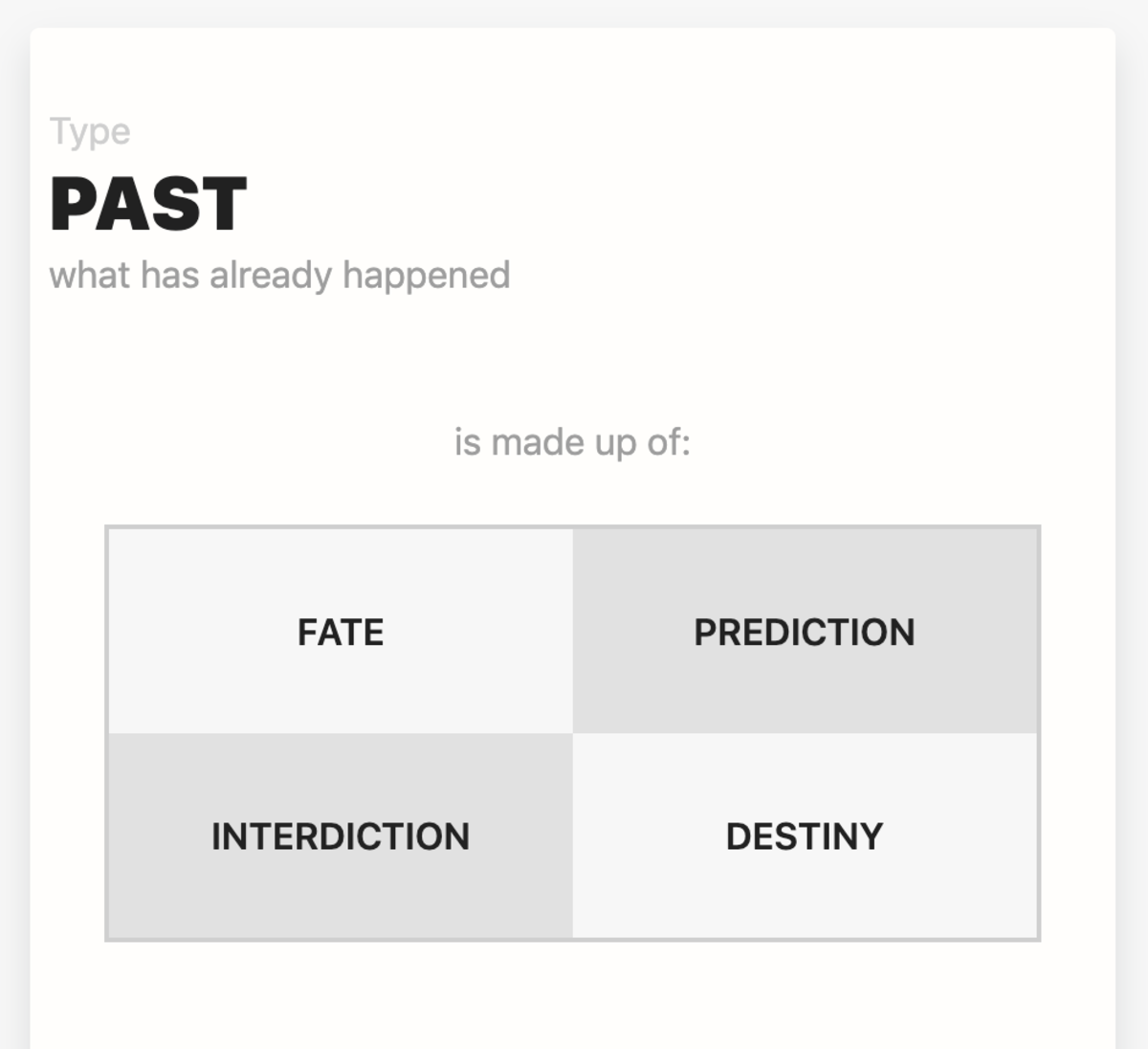

The previous article, A Synthesis In Search of a Solution, told of the correlation between the Hegelian Dialectic and Dramatica theory’s concept of the Four Throughlines:

The Main Character maintains a perspective (Thesis) and the Obstacle Character counters with the “negation” of that perspective (Anti-thesis). One gives way to the other, losing the unnecessary or non-essential components of the Thesis in exchange for all the good of the Anti-thesis, and together “resolves” the conflict with this new Synthesis.

The correlation is functional but not entirely accurate. While it is true that one of the principal characters eventually adopts the other’s point-of-view, this adoption is not the wholesale trading of one for the other.

There is a “synthesis” in the act of adopting a new perspective.

Based on your description, the MC problem story point represents the Thesis, the IC problem story point represents the anti-thesis, but what I can’t envision is either of their solutions being the Synthesis since that’s always just a binary opposition of one of the problem story points. The Synthesis isn’t “MC and IC argued over approach and it turned out IC was right so therefore the MC flips over to solution” as Synthesis specifically doesn’t mean choosing one over the other. So I’m trying to imagine what story point in a Dramatica model would represent the Synthesis between the MC and IC’s drives.

The three-fold Hegelian Dialectic is a logical formula for arriving at a solution. Dramatica is a model of human psychology focusing on inequity resolution. The former presupposes linear reasoning will come at a solution that resolves conflict. The latter makes no such assumptions, yet allows for an interpretation of narrative that fits that particular methodology of resolution.

The Hegelian only tells half the story.

Attributing Subject Matter to Perspective

In the James Bond film Skyfall, Bond acts as a proxy for the old way of doing things—and he’s not doing them very well. Having been left for dead by the country he has sworn to protect, Bond returns only to find himself at odds with his environment. With his aim off, his psycho-analysis lacking, and his physicality barely holding on by his fingertips, Bond represents the passing of the old ways.

M also stands for the old way of doing things—and she’s not doing it very well either. She is willing to do whatever it takes to keep the old guard running because that’s the best way she knows how to protect Britain. Unfortunately for Bond as far as M is concerned, the value of an agent’s life ranks below her country and her mission in importance. If she happens to break a few eggs on her way to making the perfect omelet, that is Britain, so be it.

They both share a perspective on the Subject Matter of Duty.

Bond approaches this subject matter seated in a Universe point-of-view. Bond is physically insufficient to fulfill the obligations of his job as a secret agent, and it might be time to quit. That is the inequity and dilemma that motivates him throughout the story.

M approaches the same subject matter from a Mind point-of-view. Mother is calm when it comes to being asked to take early retirement. Quitting is not an option because Britain needs MI6 to persevere—regardless of any fallout, whether political or personnel in nature. That is the inequity driving her influence on Bond.

Universe and Mind. Thesis and anti-thesis.

Diving further down into detail, we see that they are not merely opposites. Bond’s Main Character Throughline Problem Element is Deviation—an evaluation of existing outside of tolerances. M’s Obstacle Character Problem Element is Unending—an assessment focusing on continuation.

The Meaning of the End

The Synthesis of a Changed Resolve is not merely the Main Character Solution of Accurate, nor is it the Obstacle Character Drive of Unending. The eventual Synthesis is a broader appreciation of inequity resolution. The result is a greater understanding of what is an appropriate response to the same inequity in the future.

At the end of Skyfall, Bond Changes his Resolve and adopts M’s perspective—but he doesn’t simply flip a switch from Deviation to Unending. His Main Character Solution of Accurate (“Fit for duty, sir.”) is a synthesis of M’s Unending drive and a new-found appreciation for Accuracy.

Bond moves from Universe to Mind, but it’s not a complete 180 reversal. It’s more growth, or greater appreciation, of how to make sure that Deviation isn’t a Problem anymore—brought about by the influence of M’s Unending impact.

So Much More

When discussing the Synthesis portion of the Hegelian Dialectic, early practitioners—and even more modern apostles—illustrate this concept of Main Character Resolve without genuinely understanding their actions. They know the solution to be something beyond what the Main Character or Obstacle Character fight for, but they’re not entirely aware of the nature of that final resolution.

The Dramatica theory of story accounts for the broader interpretation of conflict resolution afforded by the Hegelian Dialectic—but it doesn’t merely stop there. The theory’s model of the mind’s problem-solving process details the specific nature of that eventual Synthesis, allowing the Author to pinpoint the exact source of conflict in their story.

Understanding the Purpose of Narrative Structure

Structure is order, and order is meaning.

Most believe narrative structure to be an affectation of a story. Acts exist because a story naturally falls into that kind of arrangement. This presumption that stories "have structure" misses out on the real purpose of structure: communicating an Author's Intent effectively to an Audience.

The previous article Skyfall: Finding the Synthesis in Dramatica established a possible correlation between Dramatica's comprehensive understanding of narrative and the accursed Hegelian Dialectic. What Hegel & Friends saw as synthesis is evidence of inequity resolution.

It's fascinating that you chose Skyfall for your example here because there's a completely different (non-Dramatica) interpretation of that story in which the central theme is about old ways vs. new ways.

Within the context of the Dramatica theory of story, Theme is more than a juxtaposition of incompatible truisms. Yes, the discussion starts there. However, Dramatica's version of this essential narrative concept moves further, providing greater detail and vastly more accuracy for writers wanting to improve their work.

With Dramatica, Theme is meaning. And primary to the establishment of this meaning is the Premise or narrative argument.

As you point out, both Bond and M represent the old ways, which is why both are failing to contend with the new reality. One of the best illustrations of the anti-thesis in the story isn't simply the villain Silva, but Q who says to Bond "I would hazard I can do more damage on my laptop sitting in my pajamas before my first cup of earl grey than you can in a year in the field."...the underlying thematic conflict from this (again, non-Dramatica) interpretation isn't between Bond and M.

That's because that "non-Dramatica" interpretation is spinning its wheels over a surface-level understanding of the conflict. The iceberg goes much further down. The old way vs. new way "argument" is another case of conflating Subject Matter for meaning—mistaking topic for Theme.

Obedience, Duty, Honor, Love, and Keeping Up with the Times (old way vs. new way) is Subject Matter or storytelling. It's the Topic of the story. What you want to say about Obedience, Duty, Honor, and Love are Theme.

The Totality of Theme

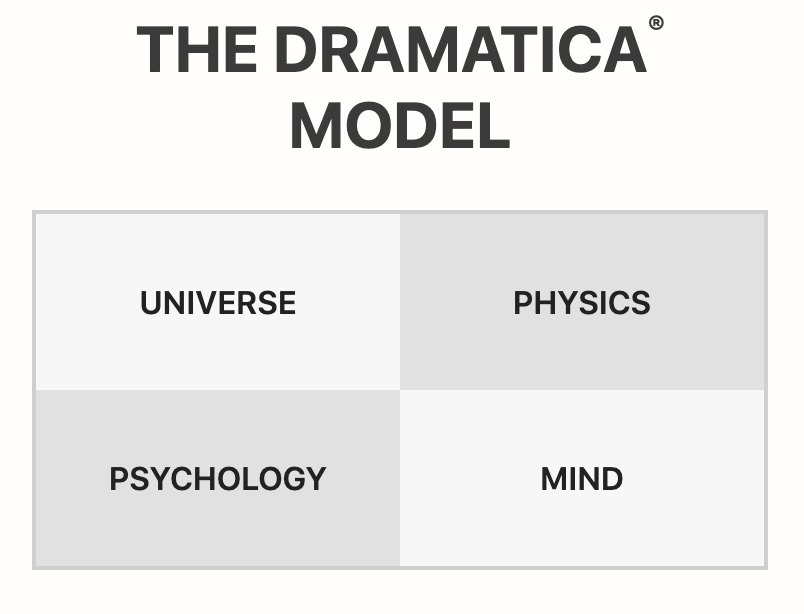

While we find the emphasis on Theme at the Variation level, the entire Dramatica model is Theme. The Domains, Concerns, Issues, and Problems of a Storyform all work together to create the thematic argument (Premise) of the story.

The thing is, what you call "subject matter" (which in almost every case is what I would call theme) is the thing I care about as a writer. When we hit the point where the underlying source of conflict is "accurate vs. deviation" we're at a level of abstraction that never shows up in the creative process for me. I'm not saying it doesn't matter, only that it exists whether I want to seek it out or not: you can't write two people in conflict with each other without there being some underlying source of conflict. Saying "they're not fighting about the old ways of being a spy vs. the new ways, it's really about deviation vs. accurate" is not a thought that would ever help me create the story.

As you point out, this underlying conflict exists whether you focus on it or not, and you certainly can't write conflict without some underlying source. The keyword here is underlying. The theme is not what the characters discuss, but rather, what motivates the quality of that discussion.

Great stories existed before the introduction of the Dramatica theory of story in 1994 (Lee, Shakespeare, etc.). Dramatica merely helps explain an essential part of why they're so great—a part that you won't find in any other discussions of narrative structure.

That part is what drives the engine of your story—the part that exists in your work, whether you seek it out or not.

Some writers get on the carousel of writing & rewriting at the writing stage. Others get on during the rewriting phase. Regardless of when you jump on, you're going to come to a point where you'll need to determine what is the underlying conflict. You might start at the very beginning of your creative process, or somewhere in the middle.

This jumping-on moment is the point at which issues of "Accurate and Deviation" start to matter. You can't determine narrative structure at the Subject Matter level of concern of "old vs. new." You need to know the specific inflection points of imbalance—like Accurate and Deviation—before you can begin building a story around them.

The alternative is fumbling around blindfolded--relying on talent and wit alone to see you through to the end.

Structure and Subject Matter

You can't reach structure through Subject Matter—you can only reach the structure, which is another way of saying order, through meaning.

Order is meaning—a slap followed by a scream carries a different meaning than a scream followed by a slap. The same Subject Matter (a slap and a scream) means something different depending upon the order in which they appear.

Meaning is only found within a context. If I hold my arm straight out and ask, Is my hand higher or lower than my feet? your answer would be "Higher."

Unless, of course, I switched the context from an Earth-centric perspective to a point-of-view centered on the Sun. Now—you might not even be able to determine high or low—because, from that perspective, we're spinning like a corkscrew through the galaxy.

Structure is order. And order is meaning. And meaning is context, and context is based on perspective or established points-of-view.

And now you know the purpose of Dramatica's Four Throughlines. The reason why there is an Objective Story perspective. And a Main Character Throughline. And an Obstacle Character and Relationship Story point-of-view.

Now you know the real purpose of narrative structure.

The Basis of a Story

The four perspectives found in Dramatica establish a context for understanding the meaning underlying the Subject Matter.

- Subject Matter != Structure

- Structure = Order

- Order = Meaning

- Meaning = Context

- Context = Perspective

- Perspective = Throughlines

Therefore, Structure equals Throughlines.

Proper narrative structure is not synthesis—it's perspective.

One man's freedom fighter is another man's terrorist. Is that an overall objective perspective? Then it's part of the Objective Story Throughline perspective. Is it something more subjective, perhaps descriptive of the dynamic within a relationship? Then it belongs within the context of the Relationship Story Throughline perspective.

When it comes to meaning, context is everything--theme is pointless without a point-of-view. Old vs. new is meaningless until put into a specific context. Setting perspective by attaching Throughlines to Domains creates the context for your story.

By allowing the Audience to appreciate your context, you permit them to invest wholeheartedly into your Premise. Your readers will understand that you're trying to say something meaningful and vital to them—and they will listen with open hearts and open minds.

Structure is not a result of story.

Story is a result of structure.

Theme Means Never Having to Say You're Sorry

Exposing the narrative elements of a story.

Great writers write without caveats. They don't backtrack, and they don't leave their purpose up to interpretation. Compelled to say something about our world and the experience of living in it, Authors take to characters and plot to state unapologetically: This is how I see the world.

And narrative structure is the carrier wave of that message.

Author and Intention

Some contend that the meaning of a story lies in the experience, that what one says bears little on the final appreciation of their work:

I was realizing the other day that there's an intrinsic incompatibility between reader-response theory, which establishes the story as the product of the reader's experience reading the story rather than anything to do with authorial intention or objective textual interpretation, and Dramatica which posits an objective, observable storyform existing in a kind of metaphysical plane beneath the text.

The Dramatica theory of story sees a functioning narrative as a model of a single human mind trying to resolve conflict. I'm not sure I would refer to this model, and Dramatica's storyform, as "metaphysical" in nature. The theory is not trying to explain a philosophical view of reality ("Evil does not exist"), but rather, theorizes the process one engages in while arriving at those types of conclusions.

Maybe I should've said "epistemological" instead.

While knowledge, justification, rationalization, truth, and belief factor into the Dramatica model, they are not treated as objects of Subject Matter the way epistemology treats them.

Reading this made me realize I'm really not sure what definition you apply to the term "subject matter" in a story. I'm sure we'd both agree that in a film like Moneyball, baseball is subject matter, but whereas to me the theme of the film is being open to new methods vs. being stuck in tradition, I get the sense you'd call that subject matter, too. In Skyfall, spying is subject matter, but for me "the old ways of human beings vs. the new ways of technology" is theme, whereas you've indicated it's subject matter.

Being open to new methods vs. being stuck in tradition is equivalent to baseball when assigning relative value to a narrative. Both are Subject Matter because you haven't said anything meaningful about those things. You've only indicated the topic of conversation within your writing.

Theme is more than focus—it's meaning.

While part of the confusion here lies in simple semantics, clarification of purpose is everything when constructing a story.

We need to differentiate between something as general as "old vs. new" with Theme because there is an infinite number of ways to explore "old vs. new." It becomes the Subject Matter of the argument because there is no indication of perspective or point-of-view. "Old vs. new" is the topic of our conversation.

The Hegelian Dialectic sees ideas in conflict (Thesis and Anti-thesis) as indicators of story structure. A Synthesis related to the topic of conversation is all that is needed to resolve the dispute. This "synthesis" is the meaning of the story under Hegelian rule.

The Dramatica theory of story goes deeper to describe the nature of those ideas and the meaning behind the eventual synthesis. With this approach, an Author gives up talking around what motivates them to write and instead, addresses the true nature of their story's conflict.

The Storytelling Layer

This differential between what we talk about and what we want to say about what we're talking about is the basis for the same story showing up repeatedly under different pretenses. While there is only one way to construct a solid argument given a point-of-view, there are an infinite amount of ways to illustrate the specifics of that argument.

The Lion King, Black Panther, and Mad Max: Fury Road all make the same argument: Give up running away, and you can reclaim a throne. Technically, Max isn't about a throne per se, but it's the same basic concept: winning something back by giving up the motivation to run.

You might think The Lion King about Responsibility, or Loyalty, Family, or Carrying on a Tradition. But are the Authors leaving the interpretations of those issues up to the audience? Or are they explicitly proving something, that if you do this, you're going to get that?

Do they possess a point-of-view?

When you begin to understand the intent of the Authors to make an argument, you recognize their shift towards one side within that discussion. The particulars of that side fall away as you look to what drives their point-of-view. Is it "old vs. new" that drives Skyfall? Or is it that the old is no longer good enough within the context of the new? Is it "Family" that operates The Lion King, or is it running away from your family that proves to be the real problem?

Isn't running away the same core problem in Black Panther and Mad Max: Fury Road?

Finding the Premise of a story is a process of extracting the narrative Elements from Subject Matter, of seeing beyond Storytelling to Storyform.

The Purpose of Structure

The Subject Matter of a story falls into the category of Storytelling. Story Structure is a part of Storyforming. That's why The Lion King, Black Panther, and Mad Max: Fury Road can be vastly different in terms of Storytelling, yet still make the same argument. Their narrative structure is identical.

So for me it feels like "subject matter" becomes far too broad a term – but I may not be catching your meaning correctly.

Subject Matter is more than setting in Dramatica--it's the life force that breathes humanity into the narrative Elements. After all, who wants to read a story about Avoidance, or Deviation?

A story is a function of Storytelling and Storyform. No meaning exists without the latter. No connection with the audience exists without the former.

To some extent, I think you've been alluding to this for years when you say that many writers will intuitively come up with a coherent storyform. That may be true, because for me, "subject matter" (e.g., "What purpose is the value of idealism in a world where it's been proven to fail over and over") is everything to me. It's the whole point of getting out of bed and writing.

I get that, but I assume you have an answer to that question. If not, then the last thing you need is narrative structure. Structure exists to convey meaning. If you don't know that meaning or have zero intent to provide a sense of things, then you're not building a narrative argument. You don't have a Premise.

If you do know the answer to your question, then you have a Premise, and you'll need a structure to make that argument. You need to prove to me, for example, that idealism sets one up to fail--assuming, of course, that that is your point-of-view. You could be coming at it from a different angle, in which case the context would shift--along with the structure.

Creating a Context for Your Audience

I can think of several examples where an idealistic mindset saved the world from tyranny, WWII, for instance. But even then, there would be many who would not agree with me. To prove that the naive idealism of the mid-20th century was a good thing, I would need to provide a consistent context. I would need a story where idealism results in triumph (Hacksaw Ridge, Saving Private Ryan, etc.).

When you don't provide that consistent context, you risk losing your audience.

Two Stories, Same Subject Matter

Clint Eastwood made two movies with the same Subject Matter--Duty, Honor, Sacrifice--and even the same setting--Iwo Jima. One film was successful in its portrayal (Letters from Iwo Jima), the other was not (Flags of Our Fathers). While the former kept a consistent context from beginning to end, the latter bounced around from one viewpoint to the next with no real common ground on which to base a solid argument (Premise).

Flags is almost unwatchable. You can't make heads or tails of what the author is trying to say about Duty, Honor, or Sacrifice. And even if you could, the point-of-view is all over the place. Its uneven formation invites criticism, making it easy for anyone to poke holes in the argument.

You can't do that with Letters from Iwo Jima.

One Author wrote Letters--Iris Yamashita. And that film scores a 91% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Flags was written by two Authors separately--and scores a paltry 73% in comparison.

Eastwood felt so compelled to get out of the bed in 2005 that he made two movies about the very same thing. The question is, which one achieved what he set out to say, and more importantly--which one will audiences remember when he can no longer get out of bed?

When Synthesis is Not Enough (Hint: Always)

The model of our mind that is a story.

Stories convey meaning—something important that adds value to our lives. Telling you that resolution resolves conflict is no more additive to your life experience than 2+2=4. Yet, many continue to generate this line of thinking with the Hegelian Dialectic and its "insightful" progression of a thesis to synthesis.

Working towards synthesis is like working towards the end of a meal. We know it's coming, and we know how it will make us feel—but what does it actually mean?

What have you added to your life?

The previous article in this series, Theme Means Never Having to Say You're Sorry, makes a case for Authors to move beyond the superficial elementary understandings of narrative structure found in something like the Hegelian Dialectic:

The Dramatica theory of story goes deeper to describe the nature of those ideas, and the meaning behind the eventual synthesis. With this approach, an Author gives up talking around what motivates them to write and instead, addresses the true nature of their story's conflict.

Hegel's synthesis simply doesn't go deep enough. It's an excellent start, but if you really want to write something meaningful—and know what it is you're writing about—Dramatica is the way to go.

The Failure of Synthesis

The Hegelian Dialectic continues to connect with writers because it offers up the feeling of narrative structure. Like it's brethren the Hero's Journey, the Nutshell, and Save the Cat!, the Hegelian brings comfort to the writer's journey. If you understand thesis and anti-thesis, surely you know how to write the next scene; you know how to finish your book. Unfortunately, these loose approximations of conflict resolution fail to get to the root motivating force of a story.

They support the writing process—they don't help it.

Consider this response from an earlier discussion regarding Skyfall and the "synthesis" that eventually resolves the conflict in that film:

The synthesis in this case comes from the integration of old tactics which gets exemplified at the end when the new M turns out to be the very same guy who was critical of the old M earlier in the movie for being out of touch yet he's willing to work with Bond. Throughout the whole movie we're dealing with this tension between new tactics and old and come to the resolution that you need a blend of both in a modern, dangerous world.

While the conversations between Bond and Q about technology play a part in illustrating the objective view of the conflict in Skyfall, they fail to factor into the conclusion of the story. Same with the conflict between Mallory and M and the strife between Mallory and Bond. Their interactions function as Subject Matter, or topics of conversation, floating on top of the actual narrative argument.

Those conversations are not what is driving the narrative—in large part because ** they're not what resolves the conflict in the story.**

The entire last act of the film is a solely brute force (the set-piece at Skyfall). How do the shootout and ensuing destruction help make the argument that the way to win is to synthesize the old approaches with the new ideas?

They don't.

Yet the Hegelian Dialectic would have you believe that a synthesis of old and new somehow solves the problem of Silva. I get that Mallory (new M) is going to be doing things a different way—but that's not how the story resolves it's conflict.

My description of the synthesis in Skyfall was a bit weak, and you're right to point it out. That said, the thematic conflict the audience is experiencing is very much "can the old ways survive in a new, technologically-driven world?" In terms of synthesis, we come out the other end with the sense that this has been answered – perhaps merely with a "the old ways are still important but you have to be open to working with those who are part of the new ways, too."

This sounds nice—but how did that stop the bad guy terrorist? More importantly, how did they arrive at this synthesis? The working Authors wants to know what to write next—and a simple notion of synthesis gives no indication of the process that led to it.

Any number of writers could write the same story described revolving around old vs. new, and have it turn out to be a completely different experience. Not simply because they're different writers with varying levels of talent, but rather that their approach towards arriving at that conclusion would be different.

Some would see that synthesis as an issue of Faith, others might see it as a need to let go of the Past. That shift in focus naturally calls for a different approach to narrative structure.

The Dramatica theory of story (and Subtxt) is interested in helping the Author identify what approach he or she wants to take on the way towards that Premise, or synthesis. Those choices set the entire structure of their piece, allowing the Author to find and fix weak spots in the narrative.

A Model of Ourselves for Ourselves

When it comes to appreciating the narrative structure of a story, the quality of the resolution is key.

Again, you raise a good point here about what ultimately resolves the conflict, but it's so buried beneath the surface that I wouldn't be able to construct Skyfall from it at all. What my writerly brain sees in that movie is: "Everyone believes the old spy ways are outdated and irrelevant, but now we're going to show Bond going back to even older ways to kick the ass of the guy who represents the rejection of the old ways."

Some writers feel inspired to write because of something they want to say; others feel inspired by a bit of dialogue or an entertaining action scene. Stories need both and Dramatica makes no attempt to capture the essence of the latter.

If you seek an understanding of your story that allows you to write with ease, then choose the one that wants to know your story. Dramatica can't help you structure scenes until it knows for sure what it is you're trying to say with your work. What you mean to say is what holds it all together—and Dramatica brings light to your intentions.

Synthesis just pays lip-service to what is a complex and multi-faceted process.

The process of our mind at work.

Writing a Meaningful End to Conflict

Tying the climactic moment to a premise.

Many writers know how they want to end their stories. They know who dies, and who lives. They might even realize why they want things to turn out that way and how it relates to their theme or premise. The question is: does that ending resolve the conflict in a meaningful way?

Is there a reason for that theme beyond something to talk about?

The horse-and-buggy days of narrative structure are long gone. And good riddance. The hours wasted trying to evoke some usefulness out of something like the Hegelian Dialectic are now behind us. And we’re all the better for it.

That 1800s philosophy—of which many still behold themselves to—is no match for the comprehensive model of the mind that is the Dramatica theory of story. “Synthesis” and “Anti-thesis” simply don’t cut it in a world that comprehends the difference between Male and Holistic thought.

Consider the conversation in this series between a novelist proficient in his craft and yours truly. The Hegelian approach lends one to see “the old ways vs. the new ways” as a theme, and a truism beyond them as a potential solution. Easily transposed from one story to the next (which narrative doesn’t find a meaningful “synthesis”?), this method fails to zero in on the particulars of said conflict.

The Dialectic doesn’t just miss the trees for the forest—it sees a green landscape where there isn’t a blue sky.

The Essence of a Synthesis

The Hegelian Dialectic isn’t all wicked. The thesis/anti-thesis/synthesis methodology works—if you understand the cause and effect linearity of its components.

To the Hegelian, conflict resolution arrives in the form of synthesis. Key to this solution is a relationship with the thesis and anti-thesis proposed earlier on in the narrative. If the thematic argument of a film like the James Bond thriller Skyfall is something as general as “the old ways vs. the new ways,” then a synthesis beyond the old and new would save the day.

But that doesn’t happen.

The only “synthesis” that stops super-villain Silva in Skyfall occurs when Bond stops fretting over issues of his physicality and returns to form—tolerating life-risking behavior without question. Shooting up the frozen ice that keeps him safe exemplifies this meaningful change. It’s a variation of the old vs. new argument, but it’s one that is intimately tied with what actually resolves conflict in the narrative.

It’s also specific and definitive.

I don’t see the connection between Bond no longer fretting over issues of physicality (which honestly I must’ve completely missed both times I watched the film) and the old vs. new argument.

When you're making an argument, you want to make sure you cover all the bases. Leave something out, and you leave yourself open for a ” Yeah, but” exchange with your Audience. You’ll want to craft a complete argument—unless you want to open yourself up to countless conversations about what your story means.

Covering All Your Bases

A complete argument explores life as experienced through the mind. Part of this examination involves the physical expression of conflict. Another, the internal manifestation of what is at odds in the context of thinking processes and fixed attitudes. Cover them all, and you’ve helped us understand a little more about what it means to be human.

Skyfall easily captures the process of physical conflict with its action sequences—there isn't a Bond film around that doesn't do that. However, in contrast to the super-spy pantheon, Skyfall goes the extra distance by exploring the internal side of things with its portrayal of Silva, M, and the dysfunctional relationship between all three principal characters.

Where the film slips up is in its development of the conflict in an external static state.

Recognizing the Missing Piece

It's no surprise to me that you don't remember the scenes where Bond contends with his deteriorated state—what we refer to in Dramatica as a Universe problem. Skyfall efficiently manages conflict in an external process context (Physics), but stumbles with the regard of the external state—namely, Bond's aging out of the spy business.

While the film starts out strong exploring this part of the argument with Bond’s inability to shoot straight, his difficulty with the physical exams, and his consternation over holding on to the elevator, it loses sight of this potential through much of Act 2—only to bring it up for a brief moment again in the final Act when he is out on the frozen lake.

Your inability to recall those scenes and make the connection with the "old vs. new" argument is proof positive that this kind of work is necessary. As a novelist, this is your life's work, and even you can't make that connection—because it was never successfully made for you in the first place.

Bond's physicality is vital to the argument because we need to see how "old vs. new" work out under the context of a fixed external state. We require that exploration of Universe.

The Reason for Four

Context is meaning—but a context is meaningless without an understanding of the totality of meaning. I means nothing without You. They pointless unless juxtaposed We. The fixed mindset domain of Mind is inconsequential unless paired with a stationary external state of the Universe.

The Dramatica theory of story is based on the quad. Its appreciations of narrative structure are meaningless unless all four items of a quad appear within a single context. Physics, Mind, and Psychology are pointless without the Universe to balance them out.

A story is one such single context.

Incomplete Arguments

Do you really see this movie as exploring what happens when a secret agent begins to fret over issues of physicality?

I see an attempt to make an argument about the old ways of doing spy work versus the realities of the modern age. I know that argument half-baked and deficient as it fails to encode the Main Character Throughline context of Universe completely.

Writers intuition naturally led the Authors of this film to include this in the story—but without something like Dramatica to keep them focused, the creators of Skyfall wrote an incomplete argument.

We all have minds. And they all work the same—more or less. We see external and internal, understand state and process, and recognize binary and analog. The Authors of the film intuitively sensed the need to address the fixed external state of things and wrote in his struggle with "getting older"—they just dropped it for much of the traditional second Act, making the final argument less convincing than it could have been.

A Meaningful End to Conflict

At the beginning of the film, a Deviation and intolerable shot sends Bond to his “death” with a drowning. In the end, he comes back to life by drowning himself at Skyfall’s frozen lake. That is behavior only M would have tolerated in the past—behavior Bond has now “synthesized” into his own repertoire.

His Resolve now Changed, Bond can get to the task of taking down Silva and resolve the rogue agent’s intolerable behavior (more evidence of a Deviation problem). Blowing up MI-6 and releasing names of secret agents is unacceptable, but ultimately unavoidable in a world where you can’t tell friend from foe—unless you meet them on the ground and face-to-face.

M was right—and is proven right by the film’s events—in her support of Bond. Her Steadfastness brought down Silva just as much as Bond’s Changed Resolve secured the future of MI-6.

An Objective Appreciation of the Author/Audience Contract

With Dramatica, you have something as simple and concrete as the appreciation of Main Character Resolve—was that Resolve Changed or did it remain Steadfast?

In Skyfall, Bond resolves to not take things so personally in the future. His Resolve is Changed. Put him on that same train in the next film, take the same shot—and he’s not going to disappear off the grid. He would most likely respond with, ” Well, I would have done the same,” because he would have—after his experiences in Skyfall.

It’s interesting because, while maybe this is true,

It is. 😂

I really never noticed it in the film in any significant way. To me it’s as if a smaller, almost trivial aspect of the story is being raised up as the most important while the things that drive me to watch the next scene disappear when looking back at the storyform. You know what I mean? I see a scene in which Silva tells Bond he’s an idiot for trying to still be one of these old-school queen-and-country spies in a new world, and I want to see if he’s going to be proven right. I don’t really care whether Bond is going to think, “Right then, I guess I really am expendable and that’s okay."

That's because when you write your novels, you're 100% locked into the subjective point-of-view of your characters. There's nothing wrong with that—it's obviously worked out quite well for you. And the popularity and success of your work are proof enough that to be a great writer you don't need to understand your work objectively.

If, however, you want to step outside of yourself for a moment, the Dramatica theory of story is your friend.

A Companion while Writing

For you, it looks as if this relationship between Author and objective theory would work best during a rewrite—singularly if you're not inspired enough by what Dramatica offers to include it in your first draft.

Note that not all Authors are like this. Dramatica is not merely a “tool for analysis,” as many would have you believe. I know several working professionals who, under extreme deadlines, prefer working the narrative structure of their stories out if not a priori, then in tandem as they write.

Dramatica and my practical application of the theory Subtxt is key to their productivity.

With or without these tools, the end result is always the same: a meaningful story with something to say. The question is—when do you want to jump on the carousel of writing and rewriting?

With the Hegelian Dialectic, you never know when to get on or off—worse, you don’t even realize the carousel exists. You end up spinning around in circles with no end in sight.

With Dramatica, writers now possess an awareness of how they think—which makes it even easier to get those intentions out and into the form of a great story.

The Debilitating Scourge of the Trope

How to cure oneself from a tragic virus of the mind.

Nothing is more caustic to the conversation of narrative structure than the trope. A breeding ground for meaningless instances of pattern recognition, the trope is the nihilist's playground. The absurdity of life played out in plot devices and genre conventions.

Recall the last article in this series, Writing a Meaningful End to Conflict, and the conversation surrounding Bond's physicality in Skyfall.

Ah, so yes, I did remember those scenes, but I chalked these up entirely to the "you're getting too old for this business" trope which while it shares the word "old" with the question of "the old ways vs. the new" isn't actually relevant except as a kind of metaphor: Bond is getting physically old, and his ways of being a spy are old, therefore Bond's body is a metaphor for the traditional ways of spying. But it's kind of cheap and to me less effective than if we'd had a younger Bond who was discovering the problems with being a traditional spy in a high-tech world.

Bond getting old exists as a metaphor for you in Skyfall because the narrative failed to integrate the Main Character Throughline fully. That's a failure of the structure, not of concept.

Thankfully, the Dramatica theory of story sees beyond the uselessness of the trope. It explains why the "you're getting too old for this" line appears in many stories within this Genre.

A Reason for Trends

The "too old for this" bit is conflict within the context of Universe—an inequity bred from the external state of things. The reason why it appears so often in Secret Agent Action films is due to the juxtaposition of the objective view of conflict and the subjective perspective. The "trope" is a result of an Objective Story conflict in Physics and a Main Character Throughline in Universe. It reflects the difficulties inherent with the work and "I'm getting too old for this."

This arrangement of perspectives contains the added-bonus of the Main Character who prefers to solve problems externally. Dramatica structure identifies this dynamic as a Main Character Approach of Do-er. When you find yourself facing a problematic external situation (Universe), your go-to preference for solving that conflict is taking external action. There aren't too many super spy films concerned with the internal components of their hero—unless you're writing about Jason Bourne.

Bourne is less "I'm getting too old for this," and more "What did I use to do?"

The Main Character Throughline of The Bourne Identity focuses on Bourne's inability to remember his past. Mind instead of Universe. The internal over the external. This thematic relationship is why The Bourne Identity feels different than most Bond films—the sources of conflict differ in a meaningful and measurable way.

A Measure of Success

The virus that is the trope clouds the mind's ability to perceive meaning. Wrapped in the comfort of * "Oh, I've seen this one before,"* the infected focuses on common elements of Storytelling rather than Story Structure. Illustrations over the content.

You see what I mean? Rolling out grandpa in a wheelchair and having him not able to shoot straight is a pretty piss-poor argument for, "see, guns are so passé. It's all about drones these days."

It's not the words themselves, but the meaning behind the words that move an Audience. The characters don't make the argument, the story makes the argument. The narrative Elements underneath define the form of that narrative argument.

Grandpa not being able to shoot straight can be seen as a sign of inadequacy. This inadequacy signals something intolerable. Indiscriminate drones that kill innocents is something unacceptable. Drones, therefore, are inadequate in matters of espionage.

The subtext beneath the Subject Matter Illustrations of "Grandpa" and "drones" connects with a single narrative Element: inadequacy. This connection forms the foundation for that narrative argument. The resonance between them is what signals to an Audience that something more exists here.

Skyfall made this connection, but then dropped it for much of the traditional Second Act.

And yet it got 92% on Rotten Tomatoes (I mention this only because you brought up movies with >90% being representative of complete storyforms).