The Audience Appreciations of Story

Understanding how the other side interprets your work

When we think of story structure, we often tend to focus on characters and plot--never thinking for once how the Audience understands our structure. The Dramatica theory of story features a handful of Audience Appreciations that help Authors understand where their story crosses over from intent to interpretation.

Predicting Who Will Listen To Your Story

Slight adjustments to the structure of your story can guarantee a larger audience.

Writing a story is one thing, finding an Audience to sit still and embrace your story is quite another. Many understand now that a functional narrative functions because it models the mind's problem-solving process; and many understand that men and women solve problems differently. Appreciating that difference makes it possible for writers to predict who will be drawn into their story, and who will simply be observers.

An Interesting Pattern of Narrative

Out of 32,767 unique Storyforms that the Dramatica theory of story can identify, there are some that appear to be duplicates. For example, if you make the following storyform choices:

- Main Character Resolve: Steadfast

- Main Character Growth: Stop

- Main Character Approach: Be-er

- Main Character Mental Sex: Holistic[^mindset]

- Story Driver: Decision

- Story Outcome: Failure

- Story Judgment: Good

- Objective Story Domain: Psychology

- Objective Story Concern: Becoming

- Objective Story Issue: Commitment

- Objective Story Problem: Avoidance

[^mindset]: If using an early version of the Dramatica application, Mindset was known as "Problem-solving Style" or "Mental Sex".

You will find two storyforms that are exactly the same in every single way except for one appreciation--the Story Continuum.[^continuum] Whether you choose to limit this narrative by options or by time, the Main Character thematics, the Objective Story thematics, the Transits in each and every Throughline, and even the Additional Plot Appreciations like the Goal and Consequence--all of those will be exactly the same.

[^continuum]: As with Mindset, early versions of Dramatica referred to the Continuum of a narrative as a "Limit". The concept of the Continuum is a dynamic. While simpler in some regards, the idea of a Story Limit fails to clue an Author in on the impact it imposes within a narrative.

Why is that?

In fact, the longer you play around with Dramatica and the various storyforms that you can create you will begin to notice a pattern: the Story Continuum really doesn't do much of anything. Other story points seem to be connected together. You choose one and instantly Dramatica makes selections for other story points you haven't even addressed yet.

Connecting Story Points Together

Choose a Main Character Approach of Be-er, like our example above, and you will notice that it limits your choices for the Main Character Domain to either Psychology or Mind. This is because a Main Character believes they will find a solution to their problem in the same area they find their problem. If your Main Character has a weight problem, they'll try to address that problem first by eating less or working out more. If your Main Character has an issue with depression, they will first try to will themselves out of that depression by trying to be happy.

Whether or not those solutions work matters little--that's where the Main Character begins to regain some control over their life and why Authors will find it a fitting choice for their Main Character's Approach.

Other story points share similar connections. Choose Steadfast for your Main Character Resolve and suddenly the Main Character and Objective Story cannot share the same Problem and Solution in their Throughlines. Switch it to Changed and now they have to have the same Problem and Solution. Choose an Objective Story Concern of Understanding and Dramatica will force you to have a Story Consequence of Conceptualizing. Choose an Story Goal of Becoming and Dramatica will balance your story out with a Relationship Story Concern of Obtaining.

At first these selections may seem arbitrary--but only until you actually take the time to think them through. In Steadfast stories it is the work that is deemed most important in the narrative and therefore the Problem and Solution between the Main and Objective Stories need not be the same. In a Changed story the opposite is true: the dilemma is factored in here and Problem and Solution are everything. The Actual or Apparent Nature of a story determines its deep underlying thematics.

Same with the Concerns and Consequences. The consequence of failing to understand something is a need to conceptualize an alternative--you have to fill that hole in your understanding with your own concept of how things fit together. If everyone in the story is going to be struggling with changing their natures and becoming something they have never been before, then the counter to that--the Relationship Story between the two principal characters--needs to explore the efforts to achieve something (or Obtain something) in order to properly balance out the narrative.

That still leaves out the Story Continuum. Why doesn't it affect anything?

Hidden Features of Dramatica

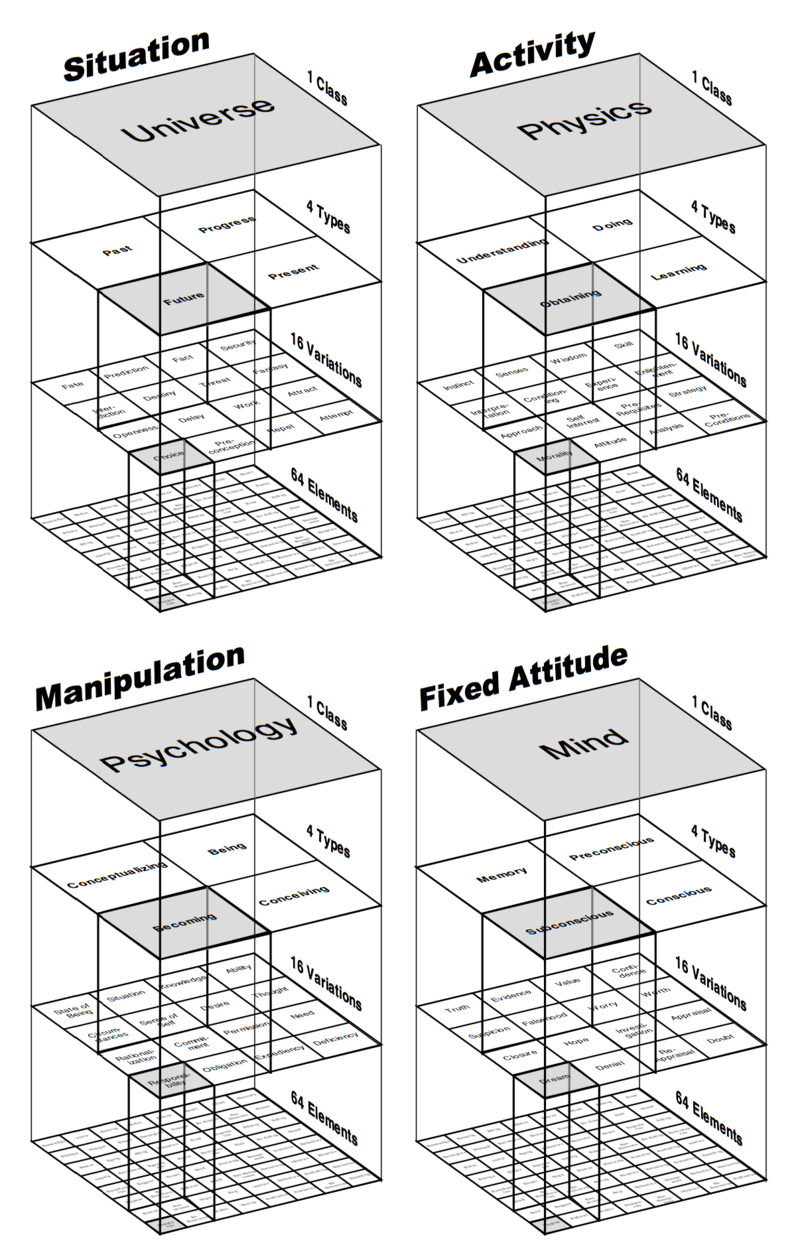

The structural model of Dramatica that many are familiar with displays a model of the mind at rest. Here, everything sits comfortably in their correct position, perfectly balanced and at peace.

When an Author begins to make choices within Dramatica, choices like the Main Character Resolve, the Main Character's Approach, or the Story Outcome, the engine within Dramatica begins to twist and turn the above into a justified version of the model. Like a Rubik's cube with rubber bands wrapped around it, the dynamic choices increase tension as they build up the dramatic potential leading up to the beginning of a story. Once set, the initial Story Driver comes along and begins to release that tension, unraveling the narrative until it can return to the model at rest once again.

The dynamic story points serve different functions in the winding up process. The Resolve determines which Throughline--Main or Objective Story--is wound up first. The Approach determines whether the Main Character Throughline is in a positive or negative position (upper or lower) and the Growth determines whether that same Throughline is in a Companion or Dependent relationship with the Objective Story Throughline.

The Story Continuum, it turns out, determines whether or not the children beneath each quad are carried over with the parent as it moves into position. The result of this is that the Author can actually determine exactly what element should be discussed in every single scene and in what order.

That is an incredible and highly informative tool for any writer--

--except that it's complete overkill and detrimental to the creative process.

Chris and Melanie felt the same when they designed the first version of Dramatica and decided to leave this feature out of the initial rollout. The absence of this Dynamic continues to this day as it seems that, after twenty years, writers and producers everywhere continue to struggle with the concept of mastering only four general Transits, or Acts, per Throughline. The Plot Sequence Report, which bridges the gap between the current offerings and the insight afforded by the Limit, only confuses and confounds those who try to master it. Going deeper would result in hearsay from the uninformed.

But there is one, very important function the Story Continuum does have that has nothing to do with the actual structure of the narrative. And it has everything to do with the Audience you are trying to reach.

Determining Who Will Listen to Your Story

While most of Dramatica deals with appreciations tied to the narrative structure of the story, there are four Audience Appreciations that predict how an Audience will react to a given narrative. The Audience Appreciation that consists of the Story Continuum and the Main Character's Mindset is known as the Audience Reach.

Audience Reach identifies which parts of your audience are likely to empathize with your Main Character. More empathy equals greater attendance equals greater word-of-mouth equals greater revenue. By combining the choices made for the Story Continuum and the Main Character's Mindset, a schematic can be graphed to predict the kind of Audience the story will attract.

Mindset is first (Male or Holistic), the Story Continuum is second (Spacetime or Timespace). In addition to having a discernible first Approach to problems, Main Characters employ a method of problem-solving that resorts to either Male thinking or Holistic thinking. Typically, these lines of thinking fall along the gender line: Males think linearly, Females think holistically. Of course, there are variations and permutations in everything and this is not to say that one cannot think using the other's problem-solving style. It simply makes it easier for the Audience to relate and plug into the Main Character when they know his or her method of thinking.

The message is clear: if you want the largest audience, make sure your Main Character approaches problems linearly and that the story witnesses dramatic potentials over temporal sequence. If you want the smallest audience, give your Main Character a Holistic Mindset and emphasize the order over the potentials.

Hard to imagine, right?

That's because it is relating a story about a character who has no concept of the pressure supposedly building up around them. They would be completely disaffected and disinterested. And so would the Audience. A relativistic mind overlooks the sequence of temporal events. Holistic thinkers don't see time the way linear thinkers do--the order of events plays little role in the relationships surrounding them.

The two middle permutations of the Audience Reach account for the blind spots seen within both Male and Female Audience members.

The Male Audience Member's Blind Spot

Guys can't stand people who don't think like they do. They don't get Holistic thinkers, as it seems completely nut-so to approach a problem by balancing the environment. This is why your guy's guy friends despise watching Moulin Rouge!. Christian (Ewan McGregor), about to be revealed as trying to win over Satine (Nicole Kidman) in front of the Duke, starts singing instead of punching and kicking his way to victory.

What?!

That's the response from a Male Mindset and one who has no concept of what can be accomplished simply by a shift in the balance of things. Singing is the perfect solution in this narrative as it resets the tone of the Duke's anger and challenges the lecherous man to see Christian in a new light. In short, holistic thinking is right 75% of the time; linear thinking is appropriate the other 75%.

But don't tell a linear-thinking Male Audience member that. He'll likely punch you in the face.

The Female Audience Member's Blind Spot

For women, the Story Continuum is their curse. Sure, they get Spacetime--balancing out everything like they usually do--they're very comfortable with the idea of dwindling options and choosing which option is the best. But when it comes to a Timespace narrative, they haven't a clue.

When you use time as your basis for understanding everything--when you see the changes and acceleration and deceleration of forces around you first before the actual things themselves--of course time isn't going to seem a factor. A minute can seem like a year, a year like a minute. If you were forced to sit in a cave for nine months while you waited for an alien creature to leave your body, you would want someway to make the days seem like seconds, wouldn't you?!

Over time this became an important, yet often overlooked and under-appreciated way of seeing the world. Turning towards the 21st century, a renewed interest in the feminine and a greater holistic understanding of the world is under way. Just don't try to make them sit through High Noon, 3:10 to Yuma, or Armageddon.[^1] They will likely despise you until you find a way to balance out their annoyance with you.

Dramatica's Ability to Predict the Future

Last week, we discussed Dramatica's ability to predict the future of cable TV and ESPN's eventual internal conflict in the article Using Dramatica to Assess Narrative in the Real World. There it was revealed how Dramatica accurately predicted the eventual state of things today based on the dramatic potential put into place two years ago. The findings were all theoretical...until they weren't.

Similarily, this notion of the Audience Reach being able to predict the potential audience for a narrative was conjecture. It wasn't based on research or analysis. It was developed based on an understanding of human psychology and the difference between the way men and women process inequities and solve problems. And it would continue to be theoretical, if it weren't for 22 years of ensuing analysis that proved it all correct.

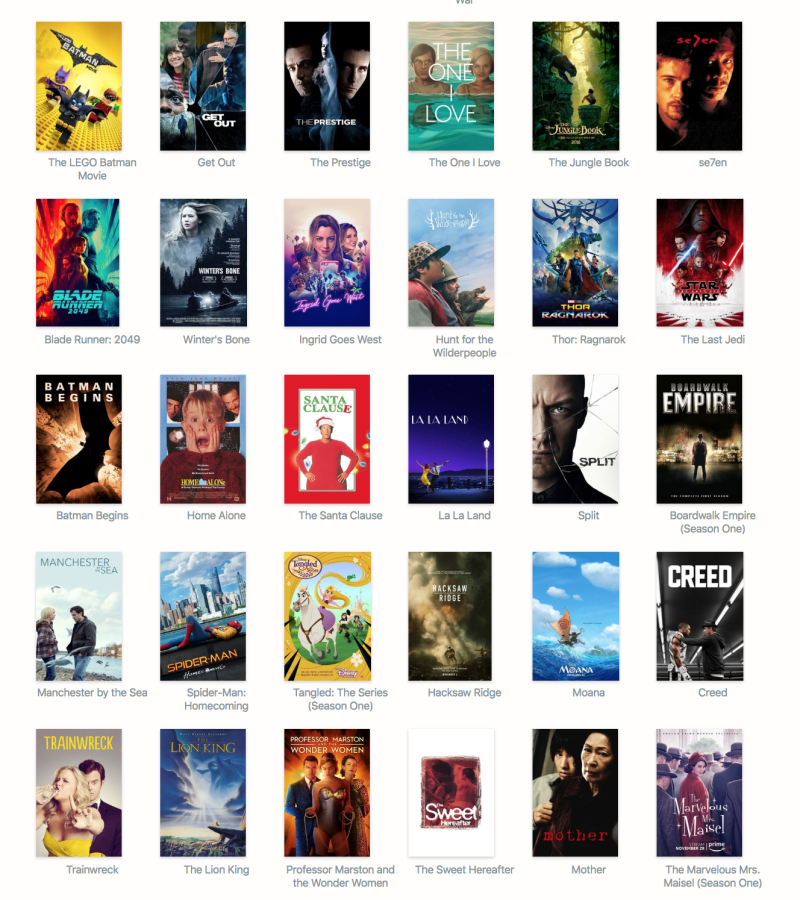

If you open up Subtxt[^subtext] and navigate to Storyform Connections, you will be presented with a collection of choices to help you better understand the presence of these story points in completed narratives. Subtxt hundreds upon hundreds of these different unique analyses of films, plays, and novels. By setting the different story points with the drop-down menus provided, you can effectively search through those hundreds of stories for storyforms that fit your choices.

[^subtext]: Subtxt is our premiere app designed to help you quickly and effortlessly outline your next story--and do so based on what you want to say, not on tropes or templates. Learn more about Subtxt.

For the purposes of this article, select MC Mindset under Dynamics and click Add Rule. Then, select Story Continuum under Dynamics and add it as well.

In seconds, you'll be presented with a startling conclusion: out of the 420+ potential narratives, over 300 of them feature Male-thinking Main Characters managing dramatic potentials. That combination accounts for two-thirds of every story analyzed with Subtxt.

That is simply astounding.

Chris and Melanie were able to predict the kinds of narratives we would find in our culture based on the psychology of the central character and the plot device put into place to bring pressure on that character.

Amazing.

Switch to Holistic/Spacetime. Over 80 different films, novels and plays that satisfy the "chick flick" notion of a Holistic Main Character juggling potentials.

Now let's try the Male's main category--Male/Timespace. Just short of twenty. Sorry guys. Though you may love them, the majority of audiences aren't really into watching the Male Mindset attack a temporal sequence.

2/3 of all stories feature Male Main Characters managing dramatic potentials. The other 1/3 feature Holistic Main Characters balancing those same potentials and Male Main Characters working a temporal sequence.

But we're still missing one last category: the Holistic/Timespace story. Set those in Subtxt and be prepared to be astounded by a prediction made over two decades ago.

Out of a set of almost 500 stories, only four fit the bill of a Holistic Main Character trapped within a Timespace.

That's right.

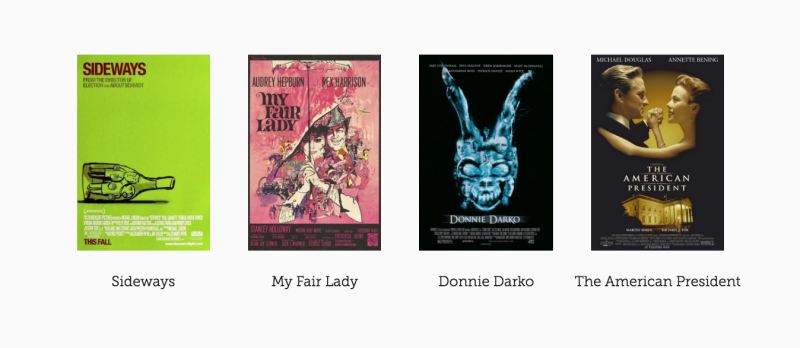

Only 1% of all stories turn out to be Holistic/Timespace stories. One of those, My Fair Lady, effectively ends about halfway in. Another, The American President actually juggles both Timespace and Spacetime. And the other, Donnie Darko, no one gets at all.

Sideways is the lone wolf here, having won AFI's Movie of the Year and Best Adapted Screenplay at the 77th Academy Awards. But we're talking Alexander Payne and Paul Giamatti here. And besides, critical acclaim doesn't always translate into higher revenue: Sideways made a little over $100G, ranking 50th in worldwide box office for 2004.

300+. 80+. 19. 4. Everyone. Women. Men. No one.

Though theoretical in presentation, Dramatica's ability to predict the behavior of writers and producers past, present, and future has no equal.

Conclusion

In 1993, Chris Huntley and Melanie Anne Phillips predicted that a majority of complete and effective narratives would feature a Male problem-solver managing dramatic potentials. They went on further to predict a pathetic amount of stories featuring Holistic minds trapped in time.

The ensuing two decades of analysis proved their postulation correct and reaffirmed the power of Dramatica to accurately and confidently predict the soundness of a narrative.

Countless hours of sweat and turmoil go into the creation of a story. Whether it be projected on a screen, presented on stage, or devoured curled up on a couch, the presence of an effective and sound narrative is all that guarantees a fondness and admiration for the work put into it.

Great narrative can be predicted. It shares a structure common to the way our own minds process and resolve problems and thus, can be accurately formulated through a greater understanding of our own psychology. Dramatica offers writers and producers the opportunity to build a better Storymind through its appreciation of the various ways each and every one of us perceives conflict. By accurately predicting human behavior, Dramatica makes it possible for creators to share their unique insights into how best to approach the conflicts we encounter in our own lives.

[^1]: Then again, don't make anyone sit through Armageddon.

How To Tell If Your Main Character Faces Overwhelming Or Surmountable Odds

Understanding the science behind narrative opens up the channels of communication between Author and Audience.

Why do some Main Characters find the conflict they face manageable while others balk under the pressure of insurmountable odds? More than a random reality at the mercy of the Author's Muse, the feeling of dramatic tension within a narrative is traceable and discernible. The direction of development within the Main Character and the overall emotional state of the story itself gives writers a clue as to the nature of that tension.

Always Four

The Dramatica theory of story always works in fours. The entire model is based on the quad—the result of the way our minds organize and process information. We see Mass, Energy, Space, and Time because we think Knowledge, Thought, Ability, and Desire. In fact ,the latter four correlate with the first four: Knowledge is the Mass of the Mind just as Thought is the Energy of the Mind.

Ability and Desire are the Space and Time of the Mind, but those are more difficult to explain, and not something we are going to cover in this week's article.

Last week we began a discussion on Dramatica's Audience Apprecations. As mentioned, most of Dramatica focuses on observable objective story points seen from the point-of-view of the Author. The Audience Appreciations offer the Author an opportunity to predict how an Audience will perceive their story based on the makeup of their narrative.

That article, Predicting Who Will Listen to Your Story, focused on Reach. By combining the Main Character's Problem-Solving Style with the Story Continuum, an Author can predict the size of their Audience. And amazing as that sounds, that is only one Audience Appreciation.

One down, three to go.

This week we will be taking a look at Essence.

Passing Judgment on the Main Character's Approach

The Essence of a story is described as the primary dramatic feel of a story:

A story can be appreciated as the interaction of dynamics that converge at the climax. From this point of view, the feel of the dramatic tension can be defined. Dramatic tension is created between the direction the Main Character is growing compared to the author's value judgment of that growth.

Dramatica predicts how the Audience will feel by defining the dramatic tension between two story points: the Main Character Growth and the Story Judgment. Balancing these two touch-points of narrative against each other, the Author gains a greater understanding of the interaction of the dynamics of their story. It defines what their story means to the Audience.

The Main Character Growth

Main Characters "arc" by either growing into something or by growing out of something. While it may seem like six of one, half a dozen of the other, the Main Character Growth defines the direction of personal development for the central character. By setting the location of the story world's larger problem in opposition to the Main Character's personal problems, the story identifies a path of growth for working through the unravelling of the justification process.

If the Main Character grows into something, then their Growth reflects a Start direction. If the Main Character grows out of something, then their Growth showcases a Stop direction.

Look to Kirk (Chris Pine) in 2009's Star Trek or Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell) in Scream--Kirk grows into his leadership role by holding out for the naysayers and the villains to Stop coming down on him. Likewise with Sidney--though slightly tweaked--she grows by getting rid of her own typically teenaged obsession with self.

On the flip side, check out Jason Bourne (Matt Damon) in Bourne's first flick The Bourne Identity or Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Muhe) in the magnificent film The Lives of Others. Jason grows into his new life by holding out for those set against him to Start revealing who they really are. Wiesler grows by gaining a sense of compassion for those he spies on.

The direction of growth the Main Character develops is only half of the equation when it comes to determining the feeling of tension in a story.

The Story Judgment

The Author also passes judgment on the story's efforts to resolve the central problem by declaring the process a Good thing or a Bad thing within the Story Judgment. Typically, this result shows up in the maintanence or reduction of the Main Character's personal angst. If the Main Character works through their issues, that is seen as Good thing. If instead their angst persists or even grows larger, than that is seen as a Bad thing.

Think of Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) in Brokeback Mountain or Mr. McAlister (Matthew Broderick) in Election--they end their narratives saddled with the weight of their own personal angst. Contrast this with Ted Kramer (Dustin Hoffman) in Kramer vs. Kramer or Joy (Amy Poehler) in Inside Out--they complete their stories relieved of stress and anxiety.

The Story Judgment can also be seen as the relative emotional appraisal of the story's characters at the end of the narrative. Were the efforts to resolve the inequity at large seen as mostly Good, or mostly Bad? Regardless of scope, the key is communicating the Author's intent to the Audience--how should they interpret the emotional judgment of the story's efforts to resolve conflict?

The Essence of Dramatic Tension

The problem with the story point of Essence is the semantic values Chris and Melanie chose to define it: Positive Feel or Negative Feel. Start/Good and Stop/Bad stories specify a story with a Positive Feel; Stop/Good and Start/Bad characterize stories with a Negative Feel.

That means Star Wars and Notting Hill feel Negative and The Omen and Romeo and Juliet feel Positive.

What?!

I'm not so sure Romeo and Juliet can be defined as positive. Under Dramatica's definition even Hamlet would be categorized as a positive story. That's insane.

When I first discovered Dramatica twenty years ago, this seemed like the craziest story point. It didn't feel right and at the time, I chalked it up to an area of the theory that was inaccurate. Every story paradigm I had encountered up to that moment had some caveat, something that wasn't quite right. My guess was that Essence fell into the same category.[^caveats]

[^caveats]: If you know anything about Dramatica, the one thing that sets it apart from everything else is the lack of caveats and exceptions. I just didn't know it at the time...

The definition of Positive Feel didn't help either:

When a Main Character's approach is deemed proper, the audience hopes for him to remain steadfast in that approach and to succeed. Regardless of whether he actually succeeds or fails, if he remains steadfast he wins a moral victory and the audience feels the story is positive. When the approach is deemed improper, the audience hopes for him to change. Whether or not the Main Character succeeds, if he changes from an improper approach to a proper one he also win a moral victory and the story feels Positive.

This sounds like Essence should be a combination of Main Character Resolve and Story Judgment, not Main Character Growth.

What exactly were Chris and Melanie hinting at? You can't really mistake a story with a Positive Feel when compared to a Negative Feel. Even the definition for Negative Feel mentions "uppers" and "downers." Reading that, one would even go so far as to assume that there would be far more "uppers" than "downers".

A Surprise Discovery

This is, of course, what I intended to find when I started writing this article. Thinking I would gain the same insightful results I did from last week's article, I figured data existed confirming the notion that Positive Feeling stories far outweighed the Negative Feels. Having spent the entire day crafting a beautifully worded 2,500+ word article, I assumed I would emerge with yet another amazing article proving Dramatica's ability to predict emotion...

...turns out I was dead wrong. The two types of stories split 50/50 pretty much down the middle. 160 to 152--with the Negative Feeling stories outrunning the Positive ones. No real insight. Nothing really interesting to add to the conversation.

A thought occurred--could it be that Chris and Melanie made a mistake in naming the semantic values for Essence?

Misleading Terminology

The definition for Essence only adds to the confusion:

When a Main Character Stops doing something Bad, that is positive. When a Main Character Starts doing something Good, that also is positive. However, when a Main Character Starts doing something Bad or Stops doing something Good, these are negative

So Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) is stopping something good and that feels negative. But Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce) from Memento is stopping something bad and that is somehow positive.

Ok...

Turns out the answer was buried within the definition of Essence and made even clearer in the QnA article on Is 'Negative Feeling' merely descriptive or is it instrumental?:

A positive story is one where the characters are doggedly pursuing a solution to their troubles--they seem to be in control. A negative story is one in which the problem is dogging the characters as they attempt to escape its effects--they seem to be at the mercy of the problem.

Ohhhhhh, now that makes sense.

Yes Leonard feels like he is doggedly pursuing a solution and yes, Star Wars feels as if the problems dog the characters as they attempt to escape its effects. That totally feels right.

Which means Positive Feel and Negative Feel characterize insufficient semantic values for the task at hand.

If Essence really is about the feeling of dramatic tension in the story then that tension doesn't feel positive or negative--

It feels Overwhelming or Surmountable.

Beset By Overwhelming Odds

Growth describes the transitory state of the Main Characters development throughout the story. Remember that the storyform has time built into it. Though it may look like a single set of story points defining the state of things, it simultaneously delineates the passage of time through the mental processes of a single human mind solving a problem.

The essence of that transition can be seen in the juxtaposition of the Main Character Growth and the Story Judgment. That feeling of Good doesn't simply exist at the end of a story—it permeates the entirety of the storymind itself—right along with the Growth. It explains the emotional state of the mind processing through this particular instance of problem-solving.

And that emotional state can be described as either Overwhelming or Surmountable.

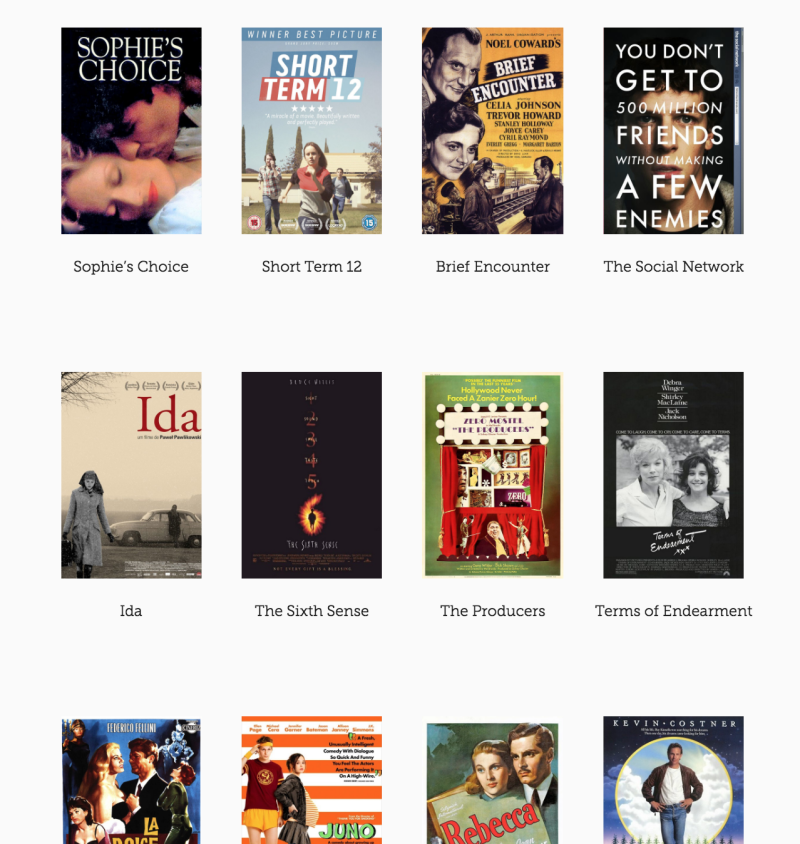

Take for instance the feeling of Overwhelming in stories marked by a Growth of Stop and Judgment of Good:

Eastern Promises, Looper, and Rocky? You don't get more overwhelming then a story about dealing with the Russian mob, a story about assassins from the future returning to the present to kill you, and a story about fighting in a boxing match you have no chance of winning.

And Joe and Ratso don't exactly find New York a hospitable place in Midnight Cowboy either.

What about a Growth of Start and a Judgment of Bad:

You probably haven't seen Eve's Bayou, but let me tell you—things don't get more overwhelming than growing up in a Creole-American fractured family in Louisiana.

Or hiding out from crooked cops in Amish Pennsylvania in Witness. Or running from a cyborg killer from the future in The Terminator.[^future] Or being an unattractive seventh grader in suburban New Jersey in Welcome to the Dollhouse.

[^future]: Apparently the future is really overwhelming. And full of time-traveling assassins.

These films and 126 more offer Audiences the opportunity to see how to approach the kinds of problems that overwhelm the senses and cloud proper judgment.

Surmountable Obstacles

On the other side, we have those stories that present a set of surmountable obstacles. Instead of overwhelmed by the weight of their issues, the characters in these stories assume control and pursue solutions because the conflict appears disputable and tenuous.

A sample of Start/Good stories:

Being John Malkovich, As Good As It Gets, and City Slickers—these are not films that overwhelm their characters with insurmountable odds. Instead, they put the characters in the driver's seat. While living inside Malkovich's head, recovering from a hate crime, and herding cattle can be difficult at times—it's not something either of them can't handle.[^simon]

[^simon]: As Good As It Gets actually consists of two different storyforms: the Romance story--which is what most think of when they think of Nicholson and his "You make me want to be a better man" line, and the Neighbors story--which features Simon Bishop (Greg Kinnear) as the gay artist and Main Character recovering from physical abuse.

Disrupting a wedding and introducing yourself into the workplace? No problem for the women behind My Best Friend's Wedding and Working Girl respectively.

Surmountable tension is manageable tension.

Witness a continuation of this trend with a sample of Stop/Bad stories:

Grave of the Fireflies—if you haven't seen it, is one of the saddest movies you will ever see. If any film had the potential of being misinterpreted as a "negative" story, this would be it.

Yet despite everything Setsuko and Seita face, they still manage to overcome it all—and it never once seems like they won't make it. Same with The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and Brokeback Mountain. Sure, being gay in a hostile world can be difficult—but it's not impossible. Neither is prospecting for gold in the remote Sierra Madre mountains.[^bogart]

[^bogart]: For most of the characters in the story--Dobbs (Humphrey Bogart) might have something to say about how everything turned out.

And standing up to the Joker in The Dark Knight or mobsters in A History Of Violence? Mortensen might have felt overwhelmed in Eastern Promises, but in History his character Tom Stall has everything under control.[^overwhelm]

[^overwhelm]: Even if Viggo's character wasn't the Main Character (and he wasn't). Story Essence applies to everyone in the story.

A Moment of Clarity

There exists a science to narrative. While many feel overwhelmed by the prospect of learning the various touch-points and mental forces behind story, the task remains a surmountable one. Either struggle with dropping preconceptions and misunderstandings and retain your personal angst (Stop/Bad), or grow into a new understanding by adding a better appreciation of story and watch your angst and anxiety slowly dissipate and fade away (Start/Good).

We prefer the latter.

Whether your own personal narrative or a fictional narrative all your own, a greater understanding of the kind of dramatic tension in a story promises a lifetime of carefree and unfettered expression. Most write to communicate an ideal, a better approach to living and breathing and existing in the world. Capture the Essence of dramatic tension in your story and convey your own unique personal message with ease and grace.

The Refusal of the Call: The Resistance or Flow Through a Narrative

The Main Character's personal problems define the flow of energy through a story.

When faced with the unknown, many Main Characters of a narrative balk and recede back into the comfort of their present surroundings. Seen by many as an indication of "refusing the call to adventure", this unwillingness on the part of the central character to participate seemingly correlates with a key story point in Dramatica. Unfortunately, this similarity exists only in semantics and if left unexplained could lead to confusion and a misappropriation of narrative focus.

In short, the simplicity and subjective nature of the Hero's Journey finds no correlation in the complex and sublimely sophisticated theory of story known as Dramatica.

The Objective Viewpoint of Dramatica

The process of using the Dramatica theory of story to frame a narrative is often foreign and uncomfortable. Most writers become writers because they enjoy placing themselves in the shoes of the characters and writing what those people see and think and feel. The subjective experience of being someone else and working through their issues and problems draws certain artists in and turns them into writers.

Dramatica wants you, the writer, to look at your story as this thing, this object you hold in your hands. Dramatica wants you to look at your story from the outside, not the inside. Removed from the emotion and subjectivity of being within, you answer questions and determine story points from an objectified point-of-view. While certainly devoid of sexiness and passion, this vantage point helps you detect holes within the narrative that you can't see from the inside.

Does the Main Character act like someone who prefers to solve problems externally before internally? Does the story reach a climax because options run out or because time runs out? Does the Main Character end the story completely resolved of their angst, or is there something still digging at them deep inside?

Writing from the Main Character's point-of-view, an Author might be tempted to lie to himself or herself as the character--and most people--would. That is why professional writers need Dramatica and why it is such a powerful tool when it comes to refining the craft of writing. An objective point-of-view saves writers from themselves.

The Audience's Point-of-View of a Story

The last two weeks found us diving into what Dramatica refers to as Audience Appreciations. By combining certain key dynamic and objective story points together, we found that a writer can pierce the veil that lies between Author and Audience and predict subjectively how the Audience will receive and react to the story. In short, by understanding and employing these story points, writers can predict how an Audience will appreciate their work.

And if they can predict how an Audience will behave based on key story points, they can also reverse the process and determine their narrative based on the Audience behavior desired.

In Predicting Who Will Listen to Your Story, writers learned that the broadest audience embraces stories that feature a Main Character who prefers to solve problems linearly and stories that come to a conclusion because of options running out. In How to Tell If Your Main Character Faces Overwhelming or Surmountable Odds, writers discovered that the feeling of dramatic tension in a story is dependent on the growth of the Main Character's personal development and the overall emotional judgment on the efforts to resolve the story's central inequity.

In this article, we intend to continue our discussion on these Audience Appreciations by focusing on the third in this series of four: the Audience Appreciation of Tendency.

Not a Refusal of the Call

The Dramatica theory of story defines Tendency as:

the degree to which the Main Character feels compelled to accept the quest. Not all Main Characters are well suited to solve the problem in their story. They may possess the crucial element essential to the solution yet not possess experience in using the tools needed to bring it into play.

Seasoned writers may attribute this story point to the "Refusal of the Call" sequence found in the Hero's Journey narrative pattern.

And they would be wrong.

Brought into greater public awareness during the 20th century by Joseph Campbell and made popular by many more in search of a grand narrative code, the Hero's Journey "structure" attempts to overlay a spiritual, or transformational, growth sequence to every narrative. The Hero's Journey is given to gross inaccuracies and rampant generalizations in no small part due to its inherent position from within the story. Those blind spots mentioned above? This is where the Hero's Journey and its subjective nature fail to capture the true nature of a narrative.

Not everything is a Hero's Journey and neither is the Main Character's tendency to be Willing to participate in a story's narrative or Unwilling-ness to see it through.

Instead, the Main Character's impetus to participate lies in a combination of that character's preference to solve problems and the specific type of plot points that drive the story forward.

The Main Character's Approach

Some Main Characters prefer to solve problems externally first, while others prefer to change themselves internally first. Main Characters can and do both, but they will always defer to one over the other as they work through a narrative. The Main Character Approach sees the primary character within a narrative falling into one of two places: either a Do-er or a Be-er.

The reason for the preference lies in the way the human mind operates: when we sense a problem we simultaneously define where we believe the solution to be.[^1] Problems do not exist without solutions in the same way that black does not exist without white. The location of that perceived solution is always in the same general area as the problem that motivates us to engage in problem-solving. If we experience an external problem, our preference is to solve it externally first. If we experience an internal problem, our first approach is to solve it internally first.

[^1]: Really, we create problems in our minds as a means of the problem-solving process. Problems don't really exist in the real world—we manufacture them in our heads. Not until we accept one-half of an inequity as a given, do we actually see the other half as the location of a potential "problem." For more, read How an Inequity—and a Story—is Made

Take William Wallace (Mel Gibson) in Braveheart--not a whole lot of considering going on there. Wallace would struggle to understand Hamlet's constant need to overthink things, and vice versa; Wallace's impulse to jump in and lop off heads would appal the Great Dane's sense of contemplation. Wallace witnesses a lack of proaction as problematic, and engages in wholesale violence to amend it.

Look at Tre (Cuba Gooding, Jr.) in Boyz N the Hood or Ned (William Hurt) in Body Heat. Getting out of the hood and addressing one's lust for a married woman require physical external approaches. You don't plan on getting out, or getting in—as the case may be--by thinking and changing yourself first.

You can, however, if you're Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) in The Social Network or Todd Anderson (Ethan Hawke) in Dead Poet's Society. Surviving a hurtful deposition by doubling down on your willful charisma and hiding one's shyness while attending an elite prep boarding school call for internal shifts of character.

Seeing Cage (Tom Cruise) from Edge of Tomorrow among a sampling of internal Be-er's may seem incongruous at first—until one takes the time to truly reflect on his personal issue within that story. Yes, he drives the story forward externally as the Protagonist, but his personal issues lie deep within the internal realm and what other people think of him.

The Main Character Approach—and therefore the Tendency of a Main Character to participate or "refuse" to join the call to adventure--focuses solely on the personal issues of the Main Character. Yet another in a long line of reasons why the Hero's Journey fails to be sufficient enough for describing the building blocks of a narrative.

The Story Driver

In addition to their familiarity with the inept "Refusal of the Call", many writers also understand the presence of several key plot points that drive a story forward. Often beginning with an Inciting Incident, transgressing through a First Act Turn, a Midpoint, and a Second Act Turn, and ending with a Concluding Event, narratives naturally self-divide into four more-or-less equal sections. Referred to as Acts, these four units of dramatic development define the beginning, middles, and end of a story.

Dramatica goes one step futher with this recognition of division by defining the type of plot point that turns a story from one Act into the next. In fact, in order for a narrative to function correctly each and every plot point needs to be of the same type: either all Actions or all Decisions, and with each forcing instances of the other. Actions force Decisions or Decisions force Actions. These Story Drivers clue the Audience in on the kind of work needed to progress through the narrative.[^work]

[^work]: Interestingly enough, the Story Driver used to be called Story Work under Dramatica 1.0. As with most things Dramatica, the original terminology tends to describe certain points of narrative with greater accuracy.

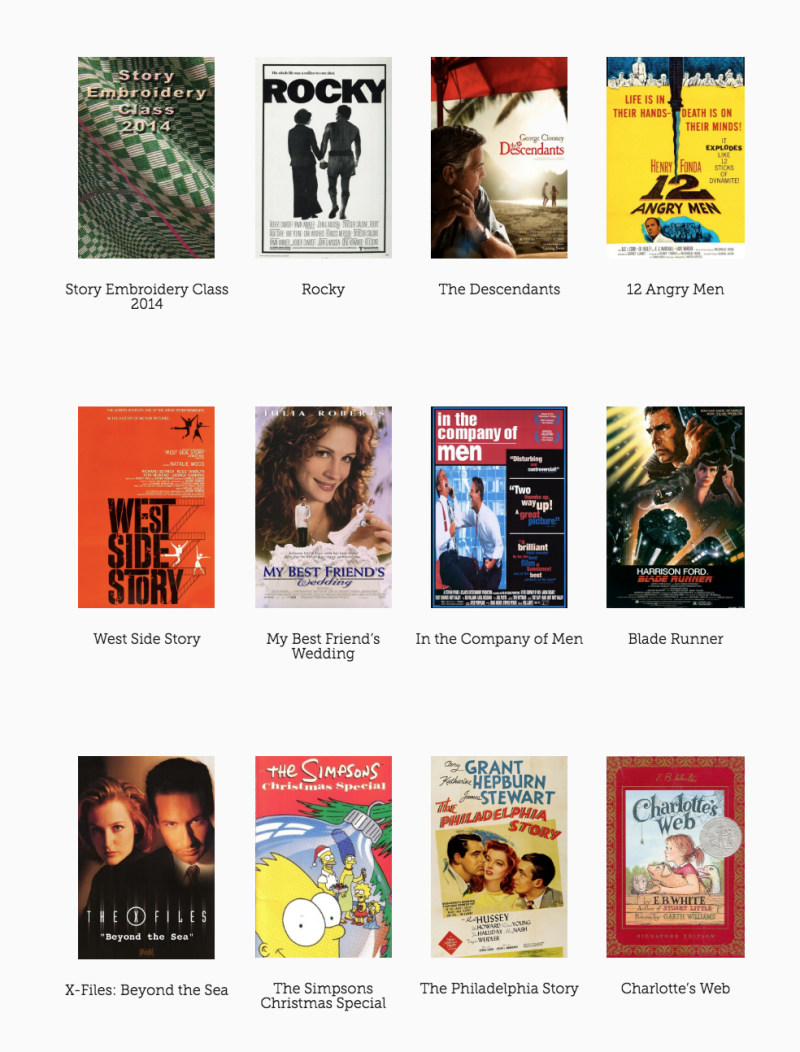

Short Term 12, Pitch Perfect, Inside Out, and Big all require Action to push the narrative forward. Dealing with troubled teens—whether in a facility, a singing competition, or just one trapped in an adult body—requires external action to accomplish anything. Even working through the internal workings of a teenage mind calls for Joy and Sadness to engage in physical activity in Inside Out. Trying to think their way through the problem would have resulted in Riley's complete psychological breakdown.

Action is not the only way to work through a narrative. Sometimes, the narrative potential of a story slowly diminishes as actions continue to be taken—until someone makes a major deicision and the conflict flares up again. These stories require decisions to push the narrative forward.

Deciding to undercut your crops, deciding to leave with a crazed gunman, deciding to leave the ghost world to help a choking kid, and deciding to follow ghosts into a cornfield—the major plot points of Field of Dreams resuscitate the narrative drive from one Act into the next by making decisions that force actions to be taken.

Same with Crazy, Stupid, Love. Typically a narrative focused on divorce sees adulterous Action as the instigator for deciding to part ways. Here, Cal (Steve Carell) faces a narrative with Decision driving the action. In order to work his way through the process he must decide how to dress, decide who to date, and ultimately decide whether or not to hold out for who he thinks is the one and only one for him.

Turns out a narrative initiated by a Decision requires a decision to wrap it all up. This happens because a story is not simply a confluence of intriguing characters and rising tension. Rather, story functions the way it does because it represents a complex model of the human mind at work.

Plot points have to be all the same type because that is how we think through problems.

A Model of the Storymind

Dramatica sees a story as a model of a single human mind working to solve an inequity. This model—while exploded out over two hours in a film or 600+ pages in a novel—theoretically happens in an instance. This is why the Story Drivers fall into either being all Actions or all Decisions: A story models resolution of a specific external or internal conflict. While the mind experiences several billion internal and external narratives a day, a single narrative can only model one or the other.

Willing to Work Through the Narrative

Juxtapose the Main Character's personal preference for solving problems with the work required to drive a narrative forward towards resolution and you find two categories of Main Characters: those Willing to do the work necessary, and those Unwilling to do the work.

While Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamil) certainly "refuses the call", he absolutely is Willing to take the Action. His personal issues lie in an external situation he would Do anything to overcome. Stuck on one side of the galaxy while his friends experience all the fun on the other side requires him to take action to get off the planet. It just so happens fighting an Empire requires the same. Put them together and you have a Willing Main Character.

Same with Woody (Tom Hanks) in Toy Story, Joe (William Holden) in Sunset Boulevard, and Clarice (Jodie Foster) in The Silence of the Lambs. Playing with your best friend, writing screenplays, and saving those screaming lambs necessitate taking Action—the same process that gets you back home, drives your benefactor to madness, and kills the serial killer. If the story calls for an event for which your Main Character is perfectly suited for, they will willingly participate.

What about Be-er's in a Decision story? Living under oppression often requires one to adapt themselves to environment; rarely does taking action result in the same progress seen above. The decisions made while under state rule often signify the difference between life and death.

In The Lives of Others and The Counterfeiters both Cpt. Weisler (Ulrich Mühe) and Salomon Sorowitsch (Karl Markovics) find themselves faced with conflict driven by the decisions of men in power. Thankfully, they both understand where this conflict originates due to their familiarity with internal pressure. Weisler personally suffers from a low opinion of himself brought about by living in East Germany. Likewise, Salomon suffers from a psychology bent on survival at any cost—regarldess of the choices one has to make.

Unwilling to Work Through the Narrative

It is when we turn to examples of Unwilling Main Characters that the concept of Tendency starts to break down:

Dr. Richard Kimball (Harrison Ford) from The Fugitive is unwilling to participate in the clearing of his own name? Detective Jake Gittes (Jack Nicholson) in Chinatown engages unwillingly in the investigation behind the murder of Hollis Mulwray?

Those don't sound remotely correct.

Tre from Boyz N the Hood? Lester from American Beauty? Rocky Balboa? He's an unwilling character too??

These only account for the Do-er's in Decision stories. Perhaps the Be-er's in Action stories will feel more Unwilling:

Chris Kyle (Bradley Cooper) from American Sniper?! If there ever was a more willing character, he would be it--he went back three times! Becca (Anna Kendrick) from Pitch Perfect feels a little more closer to unwilling, but really it feels more like she is resistant to the narrative rather than unwilling. She wants to sing in the competition.

As with last week's investigation of the Audience Appreciation of Nature, perhaps Chris and Melanie mislabeled the semantic values for Tendency.

Resistance and Flow

Recall the discussion of a complete narrative as a model of a single human trying to solve a problem. And then refer back to last week's explanation of this model as already having time factored in:

Remember that the storyform has time built into it. Though it may look like a single set of story points defining the state of things, it simultaneously delineates the passage of time through the mental processes of a single human mind solving a problem.

When reading the Tendency of the Main Character, what the Audience is really seeing is the resistance or flow of the Main Character's personal issues within the dramatic circuit of the narrative. Some Main Characters gum up the works with their personal problems, while others help facilitate the flow of conflict resolution.

Willing Main Characters amplify flow. Unwilling Main Characters build up resistance.

A Build Up of Resistance

With this in mind, one can now see how an Audience might appreciate the resistance Dr. Richard Kimball or Jake Gittes brings to the dramatic circuit of their narratives. Kimball hampers resolution with his constant need to prove his innocence. Gittes mucks everything up by constantly sticking his nose in places it doesn't belong (literally).

Same with Chris in American Sniper, Cage in Edge of Tomorrow, and even Jason Bourne in the original The Bourne Identity. The very presence of their personal issues creates a blockage within their respective stories.

What then of the Willing Main Characters?

A Tendency Towards Flow

Looking back we can see Woody, Joe, and Clarice as facilitating the flow of dramatic resolution. If it weren't for their personal issues, their stories would not have circulated quite as easily. Same with Weisler, Sorowitsch, and Skywalker. Their narratives surged smoothly because of the way each had grown accustomed to dealing with their own personal problems.

The Dramatic Circuit of a Narrative

More than "refusing a call", a Main Character's Unwillingness to participate in a narrative results in a greater resistance and dramatic buildup to any potential conflict. Conversely, a Willingness to do what is needed facilitates flow and circulation of that potential.

Regardless of nomenclature, the very idea that Chris and Melanie were able to objectify the forces within a narrative should be seen as a monumental achievement towards a better understanding of story. By allowing Authors to remove themselves from the equation, the Dramatica theory of story makes it possible to establish the resistance or flow of dramatic conflict throughout a narrative. By seeing this current as a function of personal issues multiplied by dynamic progression, a writer appreciates how the Audience will respond and can adjust the narrative accordingly.

Dramatica truly is a call to action. By refusing this call to understand story with greater precision and higher accuracy, the writer unwittingly places themselves in the role of the tragic Hero.

And that is no journey any Artist should suffer through.

The True Nature of Story

Wrapping up our series on Audience Appreciations, we elevate our understanding of narrative and begin to see it as a complex web of relationships.

Many see story superficially. They take characters and events at face value, and seek to interpret meaning behind their actions and circumstances. They see sequences and questions and characters as actual people. Approaching narrative in this way diminishes the very essence of what it means to tell a story.

Approaching narrative in this way diminishes ourselves.

The Fourth Audience Appreciation

Finishing up our four-part series on Audience Appreciations of story, we now turn our attention to the Nature of a narrative. Covered briefly in last year's article The Actual and Apparent Nature of Story the Nature of a story is defined as the primary dramatic mechanism of a story:

Which makes it sound super important. The truth is, like the Crucial Element, the Nature of a Story is one of those story points that is only important in so much as it informs the Author as to what kind of a story they are telling. You don't need to know it to write a good story or to make sure you don't have any story holes, but it is an interesting way to appreciate the kind of story you are telling.

Reach helped us define who our potential Audience would be by Predicting Who Will Listen to Your Story. Essence clued us in on the weight of dramatic tension by teaching us How to Tell If Your Main Character Faces Overwhelming or Surmountable Odds. Tendency offered us a look at the energy within a story by answering The Refusal of the Call: The Resistance or Flow Through a Narrative. Where does Nature fit in?

Integrating with the Dramatic Circuit

If you look at the three Audience Appreciations discussed in the proceeding weeks you will see a correlation between their structural concepts and the actual dramatic circuit that exists within a narrative:

- Reach defines the Potential of the circuit to connect

- Essence defines the Resistance of the circuit

- Tendency defines the Current within the circuitry

This leaves one essential component left: the Power, or Outcome of the circuit.

Strange that one finds Essence as the Resistance of the circuitry, rather than Tendency. After all, we defined Tendency as maintaining the Resistance or Flow through a circuit. But if you think of it more as the speed or current of dramatic electrons through a story as measured by the relative resistance or flow, you will find Current a more accurate assignation. Essence, on the other hand, showcases the tension built up by the possible resistance facing the story's characters.

Thinking of these Audience Appreciations as components of an electric current explains my own personal resistance or rather, ambivalence, towards the appreciation of Nature: it merely describes the Outcome or end result of all the work that came before. Why bother spending time on the relative aftermath of a dramatic circuit, when the bulk of writing deals with the formation and flow through the circuit?

The Main Character's Resolve

As with the other Audience Appreciations, Story Nature consists of two story points: the Main Character Resolve and the Story Outcome. The first manages the "arc" of the central character of a narrative, while the second deals with the resolution of the story's efforts.

The "character arc" of a Main Character consists of a combination of how that central character develops over time and the status of their world paradigm at the end of the story. As with light in the physical world, character arc can be described as both a wave (process) or a particle (state). The first part describes the process of the arc, the second keys us in on the state of the arc. Both define What Character Arc Really Means.

In Dramatica, the process of the arc finds itself within the Main Character Growth. The relative state of the arc finds a home within the Main Character Resolve.

Comparing the state of the Main Character's world paradigm at the end of a story with how they began the narrative, an Author determines either a Changed Resolve or a Steadfast Resolve. Does the Main Character see the world differently from when they began a story? If so, then their Resolve Changed; if not, their Resolve remained Steadfast.

Luke Skywalker, Neo, Sarah Connor, Michael Corleone, William Munny, and Terry Malloy alter the way they see the world and identify as Changed characters. William Wallace, Shrek, Rocky, Captain Kirk, Marty McFly, Erin Brockovich, and Salieri remain true to their personal beliefs and identify as Steadfast characters.

The Story Outcome

While every complete story contains an emotional aspect to its ending, a logical aspect exists in parallel. Concerned more with the relative nature of satisfaction or disatisfaction, this story point informs the Audience whether the efforts to achieve the story's Goal ended in Success or Failure. Varying degrees of either can be dialed in, but the overall weight of satisfaction will be felt on one side or the other.

Ted Kramer (Dustin Hoffman) secured custody of his child in Kramer vs. Kramer. Josh (Tom Hanks) made it back home in big. Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) made it out of Shawshank. Gary and Lisa defeated the terrorists in Team America: World Police. Vincent (Jamie Foxx) stopped the assassin from creating further Collateral. And Marlin found Nemo. Each and every one of these stories ended in Success.

Rocky lost. Gordie and Chris didn't get credit for finding the dead body in Stand By Me. Ennis and Jack couldn't change cultural conditioning in Brokeback Mountain. Tom Robinson was found guilty of a crime he didn't commit in To Kill a Mockingbird. And Charlie Babbitt (Tom Cruise) gave up his half of the inheritance. Each and every one of these stories ended in Failure.

The Difference Between a Dilemma and a Work

Combine the Main Character's decision to change or remain steadfast with the outcome of the efforts to resolve the story's central problem and you define what Dramatica refers to as the Nature of a story. Some stories focus on what this appreciation sees as a Dilemma, while others focus on the Work. Some stories are Actual Dilemmas while others require Actual Work. Other stories are only Apparently Dilemmas and some are only Apparently Work stories.

The problem with this Audience Appreciation, and the point that was made in last year's article, is the idea of singling out Main Characters with a Change Resolve as the only ones facing a Dilemma.

The way Dramatica combines the Main Character Resolve with the Story Outcome to define Story Nature results in this pattern:

- Stories with a Changed MC are considered Dilemmas

- Stories with a Steadfast MC are considered Works

- Stories that end in Success are Actual Dilemmas or Actual Works

- Stories that end in Failure are only Apparently Dilemmas or Apparently Works

Yet, Steadfast characters face Dilemmas as often as Changed characters. William Wallace (Mel Gibson) in Braveheart had to decide between having his guts ripped out or screaming freeeeeddoooommmmmmm!--a true dilemma if ever there was one. Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce) in Memento had to decide whether to trust John G. or shoot him in the back of the head. Christian (Ewan McGregor) in Moulin Rouge! had to decide whether or not to turn around starting singing out Your Song for all to hear. Many Steadfast stories place Main Characters in Leap-of-Faith situations where they face the same kind of dilemma as their Changed couterparts—stay the course or adapt.

So why does Dramatica confine the Dilemma to only the Changed Main Character?

Could it be that once again Chris and Melanie, the co-creators of the Dramatica theory of story, came up short when it came to defining the Nature of a story? As with the twin story points of Tendency or Essence, perhaps new or more refined terminology could more accurately describe this Audience Appreciation.

A Measure of Regret

Recently, a student of ours brought up some interesting thoughts in regards to the appreciation of Story Nature. Inspired by our recent articles, he coined the term "Story Satisfaction" to describe this combination of story points:

The MC/Audience either regrets their behavior to change or not based on the success of the goal. For example, in a Change story, the character/audience is satisfied by the efforts of the MC if and only if the outcome is success. In a way, you can combine this with personal and universal tragedies to see that whether those characters change their point of view or not, they will not be satisfied. And, in fact if they do change their POV, there is even more regret. So, it is like a way to further measure tragedy or triumph. In other words, isn't it more tragic if the MC is change, failure, bad, than just a failure-bad? And, isn't this because the change is regrettable?

Regret is an interesting alternative to Work or Dilemma and worth considering when combining Resolve and Outcome. I imagine Contentment the counterpoint. And Regret and Contentment can be easily interpreted as the Outcome, or Power, of a dramatic circuit.

Unfortunately, upon further examination this idea of "story satisfaction" fails to play out.

Looking at Resolve and Outcome together, if one changes and the story results in failure, do they regret not staying the course? Sure, that makes sense. But then again if one remains Steadfast and the story results in failure, do they not also regret staying the course? Christian from Moulin Rouge! certainly regrets what happened. Leonard doesn't, but he's crazy (and his staying the course actually resulted in Success). But I can definitely tell you that Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) from Brokeback Mountain regrets his decision to stay away from Jack.

Regret seems to be more a function of the Story Outcome: Success or Failure, rather than any particular combination of Resolve and Outcome. Stories that end in Failure are regrettable while those that end in Success bring contentment. As terminology, they function about as well as Actual and Apparent—but carry with them the unfortunate side effect of subjectivity.

Not all Failure stories are seen as regrettable. Charlie Babbit (Tom Cruise) in Rain Man certainly does not regret time spent with his brother. Detective Huxley (Guy Pearce) doesn't regret the decisions he made in L.A. Confidential. Neither does Andy Sachs (Anne Hathaway) in The Devil Wears Prada.

In addition, thinking in subjective terms of regret and contentment opens one up to the possibilty of assuming that the presence of one storyform naturally argues against the alternative.

A Measure of What is There, Not What Isn't

The reasoning involved in this idea of "story satisfaction"—that a change in approach that leads to failure makes the alternative argument that remaining steadfast would have led to success—is false reasoning. Sometimes remaining true would lead to success, but not all the time. An argument made against something does not simultaneously argue for the alternative.

If Dobbs (Humphrey Bogart) in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre had remained driven by rational thought instead of giving into his emotions would he have still ended up dead and without the Gold? Quite possibly. Likewise with Hamlet—if he had continued to pine on and on about whether to be or not to be would the memory of his father live on? There you might have an argument, but one could just as easily argue that Claudius would have run him through after the ninth-thousandth time the kid gave in to his "pale cast of thought."

The storyform argues its collection of thematic story points from a unique set of circumstances--it does not argue against or for another storyform. Just like the absence of a Timespace does not necessarily guarantee the presence of an Spacetime, the notion that a Changed paradigm leads to Tragedy does not guarantee that remaining Steadfast would have resulted in a Triumph.

On the flip side, isn't a Steadfast-success-good, more triumphant than a change-success-good because of the amount of work it takes to achieve that purity of goodness? Thinking of the philosophers in the middle ages attributing all those great steadfast qualities to God. So, that he [or she] is wholly good.

Here we run into the problem with making subjective assumptions about objective story points.

The Dramatica Way to Look at Story

In a recent blog post on evaluating the popular "Sequence Method" against the Dramatica theory of story, this idea of objectivity and subjectivity arose:

Dramatica, on the other hand, takes an objective look at story. Looking at narrative from the Author's point-of-view, it asks What is it you want to say with your story? Note the difference in mindset here--instead of dealing with experience, Dramatica deals with process. It deals with the ingredients of story.

What you want to say with your story has nothing to do with How do you want the audience to interpret what it is you want to say? Authors can predict what their story will say, but they can never know the true meaning of their work. They can never understand the true Outcome of their endeavors.

In other words—Writers can never fully understand the Nature of their story.

The result, or Power, of their dramatic circuit is an unknown—an intersection between the Author's attempt to predict and the Audience's attempt to ascribe meaning.

The True Nature of a Dramatic Circuit

Turns out Chris and Melanie were spot on in their definition of this Audience Appreciation. The Dramatica theory of story defines Story Nature as:

When the Main Character remains steadfast, he spends the entire story doing work to try and solve the problem…When the Main Character changes, he has come to believe that he is the real cause of the problem. This is called a Dilemma Story because the Main Character spends the story wrestling with an internal dilemma.

By Dilemma Chris and Melanie were referring to the structure of the entire story—the Power of the entire circuit--NOT simply the culimination moment:

A story can be appreciated as a structure in which the beginning, middle, and end can all be seen at the same time.

Another key aspect of the Dramatica theory of story that many forget[^me] is the idea that both space and time coexist within the storyform. Work and Dilemma refer to the dramatic circuit as a whole, not simply the ending. This idea I had that the Nature simply referred to the endpoint of the circuit was an error in judgment based on inaccurate linear thinking.

Chris and Melanie were defining the Holistic nature of the story by identifying the Power of the narrative throughout the entire circuit—beginning, middle, and end. Power is seen throughout a circuit as the relationships between the components, not simply something spit out at the end of a line.

[^me]: Even story consultants who have studied the theory for twenty years.

With this in mind, it becomes clear the difference between Dilemma and Work, Apparent and Actual--this story point defines the Nature of the storymind itself.

An Actual Dilemma

With an Actual Dilemma story we see Main Characters who Changed their Resolves and found Success in the Objective Story:

Ted Kramer started thinking of someone other than himself in Kramer vs. Kramer and found his son waiting for him at the other end. Chris Kyle chooses family over the military in American Sniper and finds he can help even more soldiers through his work rehabilitating disabled veterans. With Inside Out, Joy starts to give the other emotions a chance to run things in Riley's head and finds it easier to integrate into a new situation.

Overall these stories showcase Main Characters who believed themselves part of the problem, and found success by changing their approach.

An Apparent Dilemma

Contrast that with these stories where a Change in Resolve ended in Failure:

Lester started seeing things for what they really were--and ended up dead because of it in American Beauty. Jules decided to start being supportive instead of speaking out against her best friend's wedding and lost the chance at marrying her best friend in My Best Friend's Wedding. And Dr. Arroway's switch to seeing the infinite possibilities in the Universe rather than what most likely exists out there kept everyone from finding out whether they are truly alone or not.

These Main Characters believed themselves part of the problem, and by changing ended up bringing failure to the efforts to resolve the story's central problem.

An Actual Work

Switching to the Steadfast Main Characters, we first focus on stories that actually required Work to Succeed:

Jason Bourne focus on staying hyper aware of everything around him helped him take down Treadstone in The Bourne Identity. Anna Khitrova's determination to stay the course helps her secure Tatiana's baby while successfully fighting back against the Russian mafia in Eastern Promises. Ralph's steadfast belief that a signal fire was the only way off the island helped the boys stay alive until rescued in Lord of the Flies.

These Main Characters spend the bulk of their narratives doing work to try and solve the problem and find success at the end of it all.

An Apparent Work

And finally we look at those Steadfast Main Characters whose attempts to work the problem only brought about Failure:

Nader's steadfast belief that he was never to blame for anything forced the dissolution of his marriage in A Separation. Luke's refusal to stop fighting the good fight ends his life and the hopes of his brothers-in-chains in Cool Hand Luke. Butch's steadfast confidence in his his plans to get of anything finds himself and Sundance charging out in a blaze of glory in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

Unlike the previous set of Steadfast Main Characters, these characters attempts to do work to try and solve their problems were only apparently the appropriate thing to do at the time.

Apparently No One Wants to be Told What NOT to Do

Out of the 320+ stories analyzed over the past two decades with Dramatica, over 126 of them are Actual Dilemmas. That is almost half of every film, play, and novel throughout various generations and cultural trends. This signals a preference for communicating the best way to approach a problem over the cautionary tale.

The Nature of the stories analyzed fall into the following categories:

- Actual Dilemmas - 126 stories

- Actual Works - 89 stories

- Apparent Dilemmas - 66 stories

- Apparent Works - 27 stories

Apparently, not many want to be told or teach that sticking to your guns results in failure. The difference between an actual problem and an apparent problem is staggering: 215 to 93. Whether cultural bias or biological imperative, the message is clear. The overwhelming majority of narratives trend towards a focus on solving actual problems, not apparent problems.

The Power of a Dramatic Circuit

Look at any quad of elements within the Dramatica Table of Story Elements and you will always find one that doesn't quite fit in. Past, Present, and Future sit alongside Progress. Memories, Subconscious, and Conscious share space with Impulsive Directions.

And now Reach, Essence, and Tendency have Nature.

When evaluating the power of an electric circuit one doesn't simply look to the end, one must look at the operation of the entire thing all at once. When you get caught up in the individual characters of a story and their personal predicaments, you lose sight of the overall meaning and intent of the narrative. You lose sight of what it was you were trying to say.

The original intent of this series on Audience Appreciations was to pierce the veil between Author and Audience. To somehow find a new approach to using Dramatica to write our stories from the Audience's point-of-view. By diving into this weird and somehow off-beat take on Dramatica's story points we actually found something far more exciting--a greater understanding of the holistic nature of narrative.

A Relationship Between Story Elements

Effective story structure looks at story in its entirety. It does not look at a narrative as a linear progression of events asking "dramatic questions" and building up tension from one sequence to the next. Rather, it considers the entirety of character, plot, theme, and genre as one complete force of nature.

You have to think of the story as an analogy to a single human mind trying to solve the problem. It isn't about the individual characters facing a dilemma, or the individual characters going to work, but rather the characters representing facets of our minds facing a dilemma or work.

This is why it helps to think of a story as this tiny little mind you can hold in your hand. The nature of story is to speak of the power of this storymind to process problems. You're looking at the story as a holistic system of processes, you're looking at all the parts working together, relating to one another.

A Look into the Looking Glass

What is the nature of a story? Is it simply a dramatic telling of events that are meant to inspire and capture and audiences attention? Or could it be that the nature of the story is something somehow more complex and beautiful--an analogy to one of the most intricate and infinitely powerful systems found in our Universe.

Perhaps the true nature of story is to simply reflect ourselves.